Meeting India's angry spy Surjeet Singh

- Published

Surjeet Singh is mourning the loss of relatives who died while he was in jail and trying to get to know the new additions to the family

Surjeet Singh, an Indian spy, was released last week after more than 30 years in a Pakistani prison. The BBC's Geeta Pandey travels to his village in the northern Indian state of Punjab to hear his story.

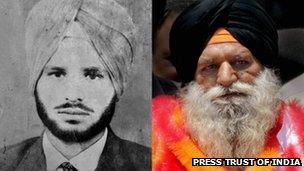

When Surjeet Singh left home to go to Pakistan on a cold winter's day in December 1981, he told his wife he would return very soon. It was 30 years and six months before they saw each other again and his jet black beard had turned white.

While he was incarcerated for spying in Lahore's Kot Lakhpat jail, his family had given him up for dead. He was utterly isolated; he didn't receive a single visitor or even a letter. Some of his time in prison was spent awaiting his end on death row. Only his faith sustained him.

"All because of the almighty. He helped me through those long years," he says.

While India's economy boomed in those three decades, tragedy struck his own family. His eldest son died, as did four of his brothers, his father and two sisters.

'Hurt and angry'

So when Mr Singh <itemMeta>news/world-asia-18621746</itemMeta> last week at the age of 73, he returned to a country and a family that had undergone radical change.

Surjeet Singh is a changed man now

Once on home ground he stunned everyone by openly admitting that he had gone to Pakistan "to spy". India has always denied claims by those returning after stints in Pakistani jails that they were spies for India. And <link> <caption>this time it was no different. </caption> <url href="http://ibnlive.in.com/news/surjeet-wasnt-sent-to-pakistan-as-a-spy-govt/268585-3.html" platform="highweb"/> </link>

But after what felt like an enormous personal sacrifice for his country, Mr Singh is hurt - and angry- by the denial.

"It was the Indian government which sent me to Pakistan. I did not go there on my own," he tells me when I meet him in his village Fidda, a little over a two-hour drive from the Golden Temple in Amritsar.

Mr Singh rejects criticism that he is claiming to be a spy "just to get some importance" or because he is "suffering from "delusions of grandeur".

In his absence, he says the army paid his family a monthly pension of 150 rupees ($3). "If I didn't work for them, then why did they pay my family?" he asks.

Mr Singh says the government has treated him 'unfairly" and that he is willing to fight for what is rightfully his. But if the authorities continue to deny that he worked for them?

"I have documentary proof, I will go to the Supreme Court to get what is my right," he threatens.

Mr Singh declined to show me the documentary proof and it is unclear exactly what his role was. He seems to have acted partly as a courier and says he did some recruiting of Pakistani agents.

He says that as a young man, he worked for a few years with the paramilitary Border Security Force before leaving it in 1968 to become a farmer. In the mid-1970s, he says the Indian army recruited him to work as a spy.

"I did 85 trips to Pakistan," he says. "I would visit Pakistan and bring back documents for the army. I always returned the next day. I had never had any trouble."

But on his last trip, things went horribly wrong.

"I had gone across the border to recruit a Pakistani agent. When I returned with him, an Indian official on the border insulted him. He slapped the agent and wouldn't allow him in. The agent was upset so I had to escort him back to Pakistan. In Lahore, he revealed my identity to the Pakistani authorities."

Mr Singh was arrested in Lahore and taken to an army cell for interrogation. In 1985, an army court sentenced him to death. In 1989, President Ghulam Ishaq Khan accepted his mercy plea and commuted his sentence into life in jail.

"Initially, I had no hope of returning home. When I was on death row, I thought this is it. But when it was commuted, I had hope."

Given up for dead

There are other Indians in Pakistan's jails. Mr Singh says there are 20-odd Indian prisoners in Lahore's Kot Lakhpat prison - all accused of spying. Two others - <link> <firstCreated>2011-06-16T15:13:11+00:00</firstCreated> <lastUpdated>2011-06-16T15:47:01+00:00</lastUpdated> <caption>Sarabjit Singh</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-13793583" platform="highweb"/> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/mobile/world-south-asia-13793583" platform="enhancedmobile"/> </link> , India's most famous prisoner, and Kirpal Singh - are on death row.

But, he says, India has done little to secure their freedom.

"The government doesn't care. It refuses to do anything for these Indian prisoners. The authorities forget that these men are also someone's husband, someone's son, someone's brother."

India's policy on the issue is not to comment.

When he did not return home as promised, his wife Harbans Kaur initially thought he was held up for work. But when days turned into weeks and weeks into months and months into years, she says she didn't know what to think.

"I didn't know whether he was dead or alive," she told me.

Daughter Parminder Kaur was 12 or 13 when her father went missing. Parminder and her siblings had to drop out of school soon after as the family couldn't afford to educate them.

Surjeet Singh returned to India amid emotional scenes

"After a while we thought he was dead. We missed him. We always had a feeling that if he was alive, we would have eaten better food, worn better quality clothes and had a better social standing," she says.

And then, suddenly in 2004, 25 years after he went missing, a letter arrived at the family home. Mr Singh had addressed it to his younger son, Kulwinder Singh Brar.

And that is when the family knew that the man they had given up for dead was alive.

"After we got his letter, I became hopeful that I will see my husband again," says Harbans Kaur.

Family happiness

Now Mr Singh is getting to know the new family members - eight young grandchildren.

It has been four days since his return and he hasn't had a minute to himself - visitors and relatives have been pouring in besides the dozens of reporters who come to interview him.

"I've lost count of how many interviews I've given. I was better off in jail," he says.

Mr Singh's outbursts and reproaches in the past few days have had some impact and help has begun trickling in.

The state administration has promised to build a concrete road to his farm, install a tubewell on his land and provide him with an electricity connection.

Punjab's Irrigation Minister Janmeja Singh Sekhon visited him on Monday and gave him 100,000 rupees ($1,826; £1,164). Some local people and groups also pitched in by collecting 250,000 rupees ($4,565; £2,910) for him.

Today, as his wife sits next to him, she cannot stop smiling.

"He still looks the same," she says. "Yes, he's gone all grey, but so have I. After so many years he's rejoined the family, it has caused me immense pleasure."

- Published28 June 2012

- Published16 June 2011