One spring just before the financial crisis struck, students at Princeton University threw a Gatsby party. “It’s going to be big,” said an organizer, promising all the trappings of the novel’s soirees. “It’s going to be grandiose.”

Gatsby parties are common, but this one stands out for its extravagance—the expected outlay was $20,000—and the particular irony of its locale. F. Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote The Great Gatsby after dropping out of Princeton, once called the school “the pleasantest country club in America,” which is one of those great insults that sounds like a compliment to those being held out for criticism.

So it is with Gatsby parties, as well. It spoils neither the book nor the new film adaptation, which opens in US theaters on May 10, to say The Great Gatsby is a critique of the American dream. It peels back a gilded veneer of success to reveal the hollow, rotting underbelly of class and capital in the early 1920s. Jay Gatsby’s weekend-long parties are lavish indictments of the whole, hard-charging scene that propelled him to sudden, extraordinary, unscrupulous wealth—”a new world, material without being real, where poor ghosts, breathing dreams like air, drifted fortuitously about,” as Fitzgerald writes toward the end.

Yet so many people seem enchanted enough by the decadence described in Fitzgerald’s book to ignore its fairly obvious message of condemnation. Gatsby parties can be found all over town. They are staples of spring on many Ivy League campuses and a frequent theme of galas in Manhattan. Just the other day, vacation rental startup Airbnb sent out invitations to a “Gatsby-inspired soiree” at a multi-million-dollar home on Long Island, seemingly oblivious to the novel’s undertones.

It’s like throwing a Lolita-themed children’s birthday party.

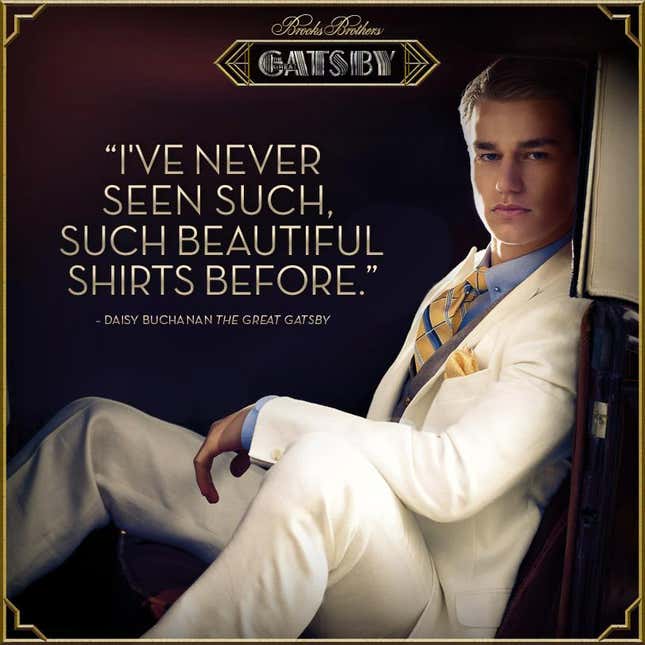

And with the impending arrival of the movie, which stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby, the literary dissonance is growing stronger. Prada threw a Gatsby party last week, which is understandable enough, given that the Italian fashion company outfitted some characters in the movie. Brooks Brothers, which in the 1920s introduced the argyle sock to America, also chipped in some costumes, and is now selling them to the public with ads like this one:

The full Daisy Buchanan quote is actually, “It makes me sad because I’ve never seen such—such beautiful shirts before.” She says it during one of the novel’s most famous scenes, as Gatsby, trying rather clumsily to impress Daisy with his wealth, flings his fine clothing across his bedroom. Daisy’s meaning is ambiguous, but the line is certainly not included as a sartorial endorsement.

Brooks Brothers is just trying to sell clothes. Less understandable are the American high school teachers who use the book to teach their students how to strive, filling in the blank, “My green light is _____.” In the novel, Gatsby’s infatuation with social class is represented by the green light on the dock of the Buchanan estate across the bay from his house. And if there’s one line that neatly, almost overbearingly, conveys the novel’s jaundiced view of the American dream, it’s this one: “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.”

At Boston Latin School, however, the green light is just good old American ambition. “My green light is Harvard,” a 14-year-old Chinese-American immigrant told a reporter visiting her English class. On the wall of the classroom, students had written their own “green lights” (pdf) on a large piece of green construction paper in the shape of a lightbulb: Pediatric neurosurgeon … Earn a black belt … Make it to junior year… Become incredibly rich.

In the novel, a guest at one of Gatsby’s parties admires the host’s library but observes that none of the books’ pages are cut. Back then, you had to cut the pages before, you know, reading them.

Fitzgerald didn’t live long enough to see The Great Gatsby come to be regarded as a great American novel, a fixture of high school English classes and college term papers. I don’t think he could have predicted that Jay Gatsby would become an icon of celebration, but it probably wouldn’t surprise him. Gatsby is us, after all, and we are inescapably American.