By Andrew Kohut, Founding Director, Pew Research Center1

Getting the American public’s attention, let alone commitment to deal with international issues is as challenging as it has ever been in the modern era. Feeling burned by Iraq and Afghanistan and burdened by domestic concerns, the public feels little responsibility and inclination to deal with international problems that are not seen as direct threats to the national interest. The depth and duration of the public’s disengagement these days goes well beyond the periodic spikes in isolationist sentiment that have been observed over the past 50 years.

******************************************

In the early 1960s, Princeton University social psychologist Hadley Cantril devised a series of questions to assess public support for internationalism. Cantril had long experience assessing the degree and nature of American isolationism. He had been President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s public opinion advisor as the U.S. was preparing to enter World War II. The Gallup Organization and, subsequently, the Pew Research Center have been tracking these measures ever since.

Over the last 50-plus years, there mostly has been broad public support for internationalism, but there have been three times when that slipped significantly:

- In 1974, after the end of the unpopular Vietnam War.

- In 1992, following the collapse of the Soviet Union when the “U.S. had no enemies.”

- In 2005 and 2006, when disillusionment set in following the protracted conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

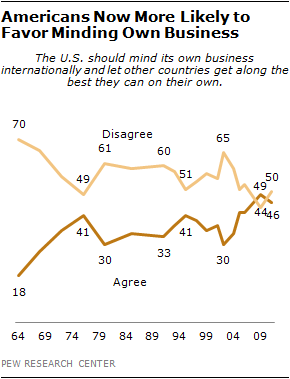

One question in the Cantril series asks respondents whether Americans should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate more on problems at home. In recent years, the percentages of Americans wanting the U.S. to mind its own business internationally has ranged from 42% to 49% — compared to an average of 36% over the 50-year study period.

That represents one of the highest measures of isolationist sentiment in this question series matched only briefly during the post-Vietnam era in the 1970s and in 1994, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Recent surveys show many other indicators of American disengagement both in general and in response to today’s foreign policy problems.

In the final month of the 2012 presidential campaign, no more than 6% of those surveyed cited a foreign policy issue, including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as the most important problem facing the country today. That compares to July, 2008 when 25% cited a foreign policy concern, including 17% who singled out the war in Iraq, even at a time when the country faced a deepening economic crisis. In January 2004, 37% cited a foreign policy concern.

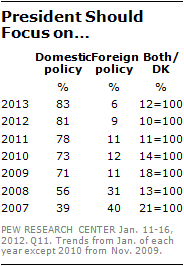

Similarly, when the public was asked in January what President Obama should focus on, 83% said domestic policy and 6% said foreign policy. That was the lowest registration of foreign policy concerns in the 15 years of Pew Research’s January survey on national priorities.

These views about America’s place in the world and its priorities are reflected in public attitudes towards specific international issues confronting the U.S. now, particularly the continuing political volatility in the Middle East and North Africa.

Nearly two years after the first of the popular protests began that came to be called the Arab Spring, an October 2012 survey found that 63% of Americans say the U.S. should be less involved in Middle East leadership changes.

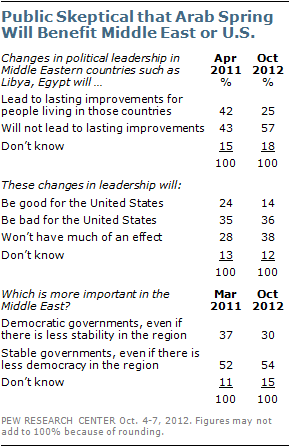

Underlying this was broad skepticism about what the aftermath of the Arab Spring would produce, especially in the wake of the unrest that followed in many countries. More than half (54%) of Americans put the priority on having stable governments in the region even if there was less democracy. Just 30% said it was more important to have democratic governments even if there was less stability.

The 2012 survey also found that Americans were increasingly dubious that the changes set in motion by the Arab Spring would lead to lasting improvements for the people in the region. Nearly six-in-ten (57%) said developments in the region would not compared to 43% who voiced such doubts in April 2011.

While President Obama has been criticized by some in Congress for not acting more forcefully to help end the Syrian conflict, the public has consistently said the U.S. does not have a responsibility to do something about the fighting in Syria. More than six-in-ten (63%) Americans held this view in a December 2012 survey, the same number expressing that opinion about intervention in Libya in a March 2011 survey.

A survey conducted after Obama authorized in mid-June sending small arms and ammunition to Syria, found 70% of the U.S. public opposed to doing so. About two-thirds of the public (68%) said the U.S. military was already too overcommitted and 60% said the Syrian opposition groups might turn out to be no better than the government. Just over half (53%) said it was important for the U.S. to back people opposing authoritarian regimes and 49% said the U.S. had a moral obligation to do what it could to stop violence.

Even when it came to the administration’s handling of the attack on the American mission in Benghazi, Libya in September 2012, which claimed the lives of the U.S. ambassador and three other Americans, the political furor in Washington was not matched by interest among the general public. A survey in May found that only 25% of Americans said they were following news of the Benghazi investigation very closely, even after new disclosures emerged about the issue.

What’s Driving Disengagement?

A combination of factors is behind this trend towards disengagement. First, the gravity of domestic concerns plays a large part, with the economy, jobs and other top domestic problems far overshadowing foreign policy and national security.

Secondly, after more than a decade of post-9/11 wars, there is a sense of war weariness. Right after the 9/11 attacks, the initial public response was to become more committed to U.S. involvement in the world, and to a multilateral approach to international affairs. In a survey conducted that October, the public said by 61% to 32% that the best way to prevent future terrorism was for the U.S. to be active in world affairs rather than becoming less involved.

But all of this quickly dissipated as the war in Iraq dragged on and came to be seen as an unsuccessful, costly quagmire whose outcome still divides the public in a survey conducted this year. (Fully 44% said it was the wrong decision for the U.S. to use force in Iraq while 41% said the decision was right). And, as fighting continued in Afghanistan, an October 2012 survey found that 54% said the U.S. military effort was not going well compared to 41% who said it was going very or fairly well.

America’s World Leadership Role

Americans consistently favor a shared leadership role for the U.S. in the world. Seven-in-ten hold this view compared to 14% who say the U.S. should be the single world leader, according to our survey on America’s global role in 2009.

Nonetheless, most want the U.S. to remain the pre-eminent military power: 57% held that view and only 29% said it would be acceptable if China or another country became as powerful.

Indeed, most Americans believe the best way to ensure peace is through military strength (53% hold that view, while 43% disagree, according to our 2012 values survey). But there is a huge partisan gap on this question. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of Republicans say the best way to ensure peace is through military strength, compared with 52% of independents and just 44% of Democrats.

However, even among Republicans, there are signs of softening. By mid-2011, 44% of Republicans said reducing U.S. military commitments overseas was a top priority, a 17 point gain from 2004, when 27% of Republicans held this view. This compares with 50% of Democrats and 43% of independents.

What Security and International Issues Matter?

There are some public concerns that have been nearly universal in Post Cold War America, both before and after the 9/11, attacks.

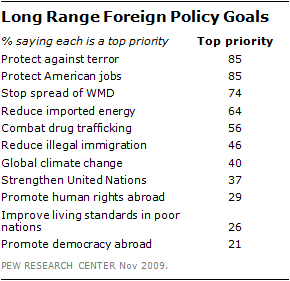

- Protect the U.S. against terrorist attacks.

- Prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction.

- Protect American jobs.

In November 2009, large majorities of Americans indicated that each of these was a top priority for American foreign policy.

A second tier of concerns includes increasing energy independence, combating drug trafficking, global climate change and reducing illegal immigration.

A third tier includes promoting human rights, improving living standards in poorer countries and promoting democracy abroad; fewer than three-in-ten Americans say each of these is a top priority.

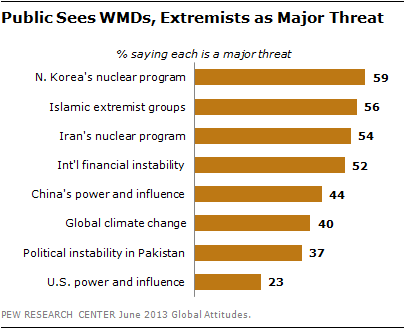

Arrayed against those concerns are the worries that Americans have about the biggest threats facing the country, including worries about WMDs and terrorism, as well as international finances.

A June 2013 Global Attitudes survey found that nuclear proliferation in North Korea and Iran remain top priorities, as do Islamic extremist groups – over half of Americans rank each as a major threat to the United States.

A second tier of threats that concern Americans includes China’s emergence as a world power, political instability in Pakistan and global climate change.

50 Years of American Two-Mindedness on International Relations

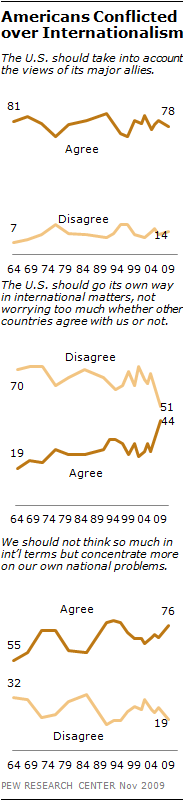

In spite of the fact that Americans are currently expressing more disengagement than they have in previous years, the public has consistently expressed conflicting perspectives over international relations.

Americans have agreed that “In deciding on its foreign policies, the U.S. should take into account the views of its major allies” by large majorities for the past 50 years. In addition, large majorities have consistently disagreed with the statement “Since the U.S. is the most powerful nation in the world, we should go our own way in international matters, not worrying too much about whether other countries agree with us or not.”

However, most have also taken the view that Americans should concentrate more on national problems, and building up strength and prosperity here at home. In 2011, 52% of Americans said that the U.S. “should deal with its own problems and let other countries deal with their own problems as best they can.”

Indeed, while this is a particularly challenging time for internationalism, global engagement does not come easily and naturally to an American public that more often takes a Jacksonian view of the world than a Wilsonian one. And when the President of the Council of Foreign Relations, Richard Hass, no less, writes that America should take a breather given that international threats tend to be limited and regional and “none rises to the level of being global, immediate and existential,” he will not get many arguments from middle America.