Q&A: Rob Sheridan, Art Director of Nine Inch Nails

Nine Inch Nails’ most prominent visual theme evolved from decay into glitch during the With Teeth (2005) and Year Zero (2007) eras though the work of Rob Sheridan (Tumblr), a Los Angeles-based artist, designer and photographer. Sheridan started working with Trent Reznor in the late ’90s at a time when he was a budding artist with a well-run NIN fansite and Reznor was looking to expand his digital presence. As their partnership grew more and more collaborative, Sheridan’s role evolved from designer and photographer to Art Director. He also went on to create glitched visuals for Reznor’s work on The Social Network soundtrack in 2010 and with How to destroy angels_ this year in addition to becoming Reznor’s bandmate in the latter project. Despite being just as swamped as Reznor with NIN’s comeback, Sheridan was kind enough to speak with me over email about how he matches visuals to Reznor’s music.

Jill Krajewski (One Week One Band): What interests you about glitch art?

Rob Sheridan: I’ve always been fascinated with things that feel off, things that break formality or break the expected in interesting ways. When I started working with Nine Inch Nails and found myself tasked with visually representing the themes and emotions and sounds of the music, visual glitching was a natural fit. Trent has always played with things that sound slightly “wrong” in his music, and seeking the same visual metaphors often leads me to trying to use visual tools in “wrong” ways. Over time that’s meant dragging paper through broken printers, pouring liquids onto scanners, intentionally breaking cameras, corrupting code, disrupting signals, and on and on. But it depends entirely on the project and the themes and emotions behind it - you won’t find a trace of glitching on some of the albums I’ve done with NIN, because it wasn’t appropriate thematically.

OWOB: Your use of glitch art for The Social Network and Year Zero seems to reflect the backdrop of corruption in both works. Why do you feel glitch art suits this theme?

RS: Well glitch art is, by its nature, corruption. For Year Zero it was a really natural fit, and the use of glitching came initially out of the story. The idea in the mythology was that everything visual in the Year Zero campaign - album art, websites, video footage - had been sent here from the future. So the glitching was a way of visually showing that story element, showing that the data had been corrupted to varying degrees during the transmission back through time. Corruption being a thematic tie-in with Year Zero’s story made it that much more perfect.

For The Social Network, the look of corrupted images played perfectly into not only the themes of corruption in the film, but of the way we portray ourselves digitally on Facebook. The look of it hinted at a darker side to what would be otherwise benign photos.

OWOB: Is there a theme behind your use of glitch art with How to destroy angels_?

RS: I came to the world of analog glitch while seeking out visual inspiration for the new HTDA record [Welcome Oblivion]. Wanting to move away from databending and try something different, I found that the analog equipment I was starting to experiment with created a process that interestingly mirrored what was being done on this album with audio equipment in the studio. And the way the process distorted imagery tied in really well with the themes I wanted to explore. There are themes of singularity, of a sort of end to mankind in an apocalyptic yet distinctly non-apocalyptic sort of way. There are themes of information overload, an increasing inability to process the amount of data that’s coming in. None of that probably makes any sense, but I don’t want to go into it in too much detail. The themes are closely connected to the themes of the HTDA album, and I’d rather people be able to experience it themselves and have their own takeaway on what it’s about.

OWOB: How do analog errors and databending compare to emulating the glitch look manually for you?

RS: The thing I find most interesting and refreshing about databending and analog glitching is the lack of control. As a Photoshop guy I’m really into having a lot of control over every detail, so it’s great to step out of that comfort zone and work with methods that have a high degree of randomness to them. With databending, after enough experimentation I could start to control the results in a very loose way, but the specific details were still very random, and I could always get something I wasn’t expecting. The process injects new ideas and you can react to how they feel and follow certain paths. It’s sometimes a much more inspiring way to work than staring at a blank document and relying entirely on your own brain to fill in every pixel. It’s kind of more like cooking than painting.

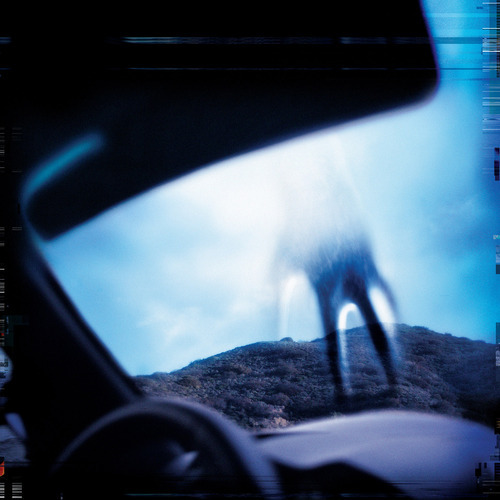

It’s also a wonderfully honest method of creating imagery at a time when everything is Photoshopped to death. The current analog method I’m using involves processing images through broken VCRs and disrupting their signal into an old CRT monitor, then photographing the screen and catching brief moments of chaos. But the fine texture of the CRT monitor in the images makes them fairly un-editable in Photoshop. When I take a normal photo I know I still have a ton of control over it in Photoshop - I can transform it into an entirely different image. With this glitching method, all the creation has to happen in the process - nothing is done in Photoshop after, aside from tweaking colors and sometimes adding text. I’ve spent a lot of years meticulously recreating the randomness of digital glitches in Photoshop, and sometimes that works fine - but there’s nothing quite like the real thing.

OWOB: How do you feel about the use of glitch art in other forms of art and commercially?

RS: I’ve noticed a ton of mainstream use of glitch as a stylistic element in the years since we did Year Zero. I see it a lot in movie and TV title sequences, and in a lot of big video games. Sometimes the resemblance to what we did in Year Zero is pretty uncanny, I would love to think that it was an influence on some people.

I know there’s a tendency for people to grumble when something they love and feel a certain degree of ownership over gets adopted by the mainstream, but I like to look at it as a validation of sorts that it’s resonating with a lot of people. And the only thing you can do is accept it and embrace it, or push yourself further into territories the mainstream hasn’t picked up on yet. My only complaint is that the glitch “look” is becoming so commonplace, and is often poorly faked with software, that people tend to assume everything is a Photoshop plugin, even when it’s actually a laborious manual process. I get the “hey how do I do that in Photoshop?” question a lot, and take a certain delight in the opportunity to explain processes like hex editing and disrupting analog signals.

OWOB: Why do you believe glitch art has grown in popularity?

RS: Every year I see more and more artists doing really creative things with glitch - not just in visual art but in motion, in music, in interactive. There are even iPhone apps for creating glitch art (Decim8 is a particularly excellent one). It’s an inevitable reaction to the world becoming more digital, and the resulting itch for people to want to push back on digital perfection, and break it. As technology becomes more pervasive in our lives, the idea is that everything becomes more organized, more efficient, more convenient. And yet the challenge of rewiring our brains, our social structures, our ways of processing information and interacting with the world around us - that can feel very chaotic and overwhelming. To me there’s just something cathartic about unleashing errors and chaos into ordered systems. It’s like bringing some humanity into the machine - imperfection being, really, the essence of humanity.

Breaking things can be just as creative as building them, and glitch draws in the type of people who get a new tool, or a new device, or new software, or a new instrument, and think - how can I use this in a way that wasn’t intended, and get interesting results?

Photos by Rob Sheridan. Additional photography by Tamar Levine.