You've Spent Years on Your Ph.D.: Should You Publish It Online for Free?

Why the American Historical Association is encouraging graduate programs "adopt a policy that allows the embargoing of completed PhD dissertations"

The American Historical Association has spied itself a Problem with a capital P and it is determined to do something about it. That problem? Too many people are reading history doctoral dissertations on the Internet.

This madness must be stopped, the AHA thought to itself. We can't have all these people reading scholarly works online, for free. And so, the AHA crafted a solution, not a perfect one -- what solution is? -- but something that might help, something that might prevent all these people from reading all these dissertations. Yesterday, in a statement posted online, where everybody may read it (and many have), the AHA encouraged graduate programs and university libraries to "adopt a policy that allows the embargoing of completed PhD dissertations" from the Internet for six years. It is the AHA's position that they want universities to provide a choice to young PhDs, but I worry they are addressing the wrong problem, and doing so with the wrong tool.*

Let's first hear from the AHA in its own words:

The American Historical Association strongly encourages graduate programs and university libraries to adopt a policy that allows the embargoing of completed history PhD dissertations in digital form for as many as six years. Because many universities no longer keep hard copies of dissertations deposited in their libraries, more and more institutions are requiring that all successfully defended dissertations be posted online, so that they are free and accessible to anyone who wants to read them. At the same time, however, an increasing number of university presses are reluctant to offer a publishing contract to newly minted PhDs whose dissertations have been freely available via online sources. Presumably, online readers will become familiar with an author's particular argument, methodology, and archival sources, and will feel no need to buy the book once it is available. As a result, students who must post their dissertations online immediately after they receive their degree can find themselves at a serious disadvantage in their effort to get their first book published; it is not unusual for an early-career historian to spend five or six years revising a dissertation and preparing the manuscript for submission to a press for consideration. During that period, the scholar typically builds on the raw material presented in the dissertation, refines the argument, and improves the presentation itself. Thus, although there is so close a relationship between the dissertation and the book that presses often consider them competitors, the book is the measure of scholarly competence used by tenure committees.

In the past, most dissertations were circulated through inter-library loan in the form of a hard copy or on microfilm for a fee. Either way, gaining access to a particular dissertation took time and special effort or, for microfilm, money. Now, more and more university libraries are archiving dissertations in digital form, dispensing with the paper form altogether. As a result, an increasing number of graduate programs have begun requiring the digital filing of a dissertation. Because no physical copy is available, making the digital one accessible becomes the only option. However, online dissertations that are free and immediately accessible make possible a form of distribution that publishers consider too widespread to make revised publication in book form viable.

Of course, I am being a bit glib about what the AHA believes is a problem, and it's not that too many people are reading history online but the effect of that access -- that young scholars will be unable to publish their work as a book, if everybody can already read it online for free. And if those scholars can't publish a book, they'll be at a disadvantage when competing for tenure-track jobs.

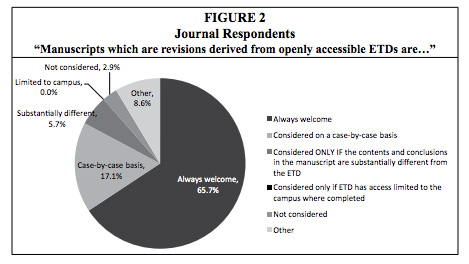

The thing is, it's not so clear that this is in fact the case. A recent survey of academic journal editors found that only a very small percent (2.9) would explicitly not consider for publication something that was already available online. The vast majority said they were either always open to "electronic theses and dissertations" (ETDs) or would evaluate them on a case-by-case basis (a practice some might refer to as editing). An earlier study found that "only 1.8% of graduate alumni reported publisher rejections of their ETD-derived manuscripts."

That doesn't get right at the question of how much the fact of online publication will sway an editor's judgment, but the point is that the relationship is unclear. There probably is a negative impact for dissertations that are particularly narrow and have a small potential audience, but for those that are more general, the effect could work in the opposite direction: Publishing online could generate buzz, enlarging rather than shrinking the pool of readers, making book or journal publication more, not less, attractive for publishers. Whatever the case, wherever the balance of these countervailing effects lies, it seems that more research into the relationship between online access and book viability should be done before a policy of a six-year embargo is endorsed.

The AHA is acting out of a genuine concern for the career prospects of younger scholars, and that is admirable. The trouble is, as the Digital Public Library of America's Dan Cohen tweeted, "Rather than trying to push other levers, or experimenting with other ways to disseminate historical knowledge, the AHA's default is to gate." He later added, "It's the passivity in the face of what is, the lack of initiative to explore other models *as well*, that's disappointing."

Ultimately, what is so frustrating about the AHA's stance is that it seems to view the purpose of historical scholarship narrowly, as a means to securing employment. But the value of history is a public one. The late Roy Rosenzweig, then the vice president of research at the American Historical Association, danced around this in a 2005 essay later quoted by Cohen:

Historical research also benefits directly (albeit considerably less generously [than science]) through grants from federal agencies like the National Endowment for the Humanities; even more of us are on the payroll of state universities, where research support makes it possible for us to write our books and articles. If we extend the notion of "public funding" to private universities and foundations (who are, of course, major beneficiaries of the federal tax codes), it can be argued that public support underwrites almost all historical scholarship.

Do the fruits of this publicly supported scholarship belong to the public? Should the public have free access to it? These questions pose a particular challenge for the AHA, which has conflicting roles as a publisher of history scholarship, a professional association for the authors of history scholarship, and an organization with a congressional mandate to support the dissemination of history. The AHA's Research Division is currently considering the question of open--or at least enhanced--access to historical scholarship and we seek the views of members.

The AHA attempts to bow to the value of "full and timely dissemination of new historical knowledge" by recommending an embargo "only for a clearly stated, limited amount of time, and by encouraging other, more traditional forms of availability that would insure a hard copy of the dissertation remains accessible to scholars and all other interested parties." What if instead the AHA sought to celebrate students who sought to bring their work to a wider audience? What if it encouraged hiring committees to focus less on books as the symbol of scholarly success and looked more at the scholarship itself, or the impact it had on the wider world?

With its statement, the AHA says that it accepts that hiring practices must remain what they are, that history is and will remain a "book-based discipline" (a claim historian Adam Crymble rightly disputes), and that the public good must remain at odds with that of the discipline and its practitioners. This sort of thinking, Cohen wrote last fall, is representative of "a collective failure by historians who believe -- contrary to the lessons of our own research -- that today will be like yesterday, and tomorrow like today."

* This paragraph has been updated to more clearly reflect the AHA's position.