LA River's flood role is 'paramount'

- Published

Any moves to modify the Los Angeles River, to return parts of it to a more natural setting or to capture water, need to be implemented with care.

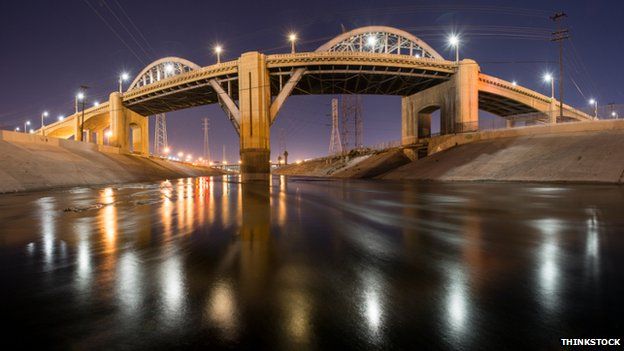

Scientists say the key job of the concrete channel, which has featured in countless films and pop videos, is to protect the city from damaging floods.

And that role is likely to become more challenging if climate change brings heavier rains, they argue.

Alternatives to the river's current brutalism will not be easy to find.

"This is not a simple problem; it's not a matter, for example, of taking out half the concrete," said Bill Patzert from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

"One of the things the river attempts to do is to move water rapidly - the particular design, the angle, the slickness of concrete. It does that brilliantly.

"We've done something right through the middle of one of the most densely populated places in the world, and redesigning it is going to be very difficult."

Dr Paterzt and colleagues submitted an abstract on the topic to this year's American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting.

They are conducting research that seeks a vision for a "greener" LA River.

The city has boxed itself into a very complex position.

On the one hand, its four-million-strong population requires a huge volume of water, 70% of which is imported from sources that include Northern California and the Colorado River.

And yet when rare, heavy rains fall on arid LA, most of that water is sent straight into the Pacific Ocean via the city's 2,500km of storm sewers and the famous 80km-long concrete conduit.

The river's flood-protection function was put into effect after catastrophic downpours in 1938, which resulted in more than a hundred fatalities and the destruction of over 5,600 buildings.

Since that time, the population of the megacity has boomed and there is now very little space to make modifications to the drainage system as it exists.

Leaving aside the desire to see a more aesthetic river (it cannot be just a backdrop for the film and music industry), there is also a pressing need to capture more water.

This could take the form of catchment basins, where water is diverted out of the river to replenish ground aquifers.

That will be expensive because it will almost certainly require the rezoning of some districts.

But Patzert's and colleagues' point is that whatever changes are introduced, they have to be balanced against the mitigation of future flood risk.

Co-worker Shelley Shaul-Regalado told BBC News: "The atmosphere is warming and, looking into the future, will be capable of holding more moisture. This increases the probability of more intense storms.

"This is consistent with our research. Whether this means more rainfall per year is a concern and not yet understood.

"Simply, we should plan for future storm events being wetter. This increases the likelihood of larger flows in flood control channels like the LA River."

The team reports that eight record storms, each with rainfall totals over 28cm, since the 1938 flood could have created devastating deluges were it not for all that concrete.

The US Army Corps of Engineers very deliberately put extra capacity into the flood channel when building it. At its peak, the river can accommodate a discharge of 3,600 cubic metres per second.

During the 1938 flood event, the discharge reached more than 2,000 cubic metres per second in places. But the discharge from similar storms now would very likely be larger because of all the extra run-off resulting from increased urbanisation.

"Today, a storm similar to the famous 1938 event would surely test the present flood-controlled LA River," said Shaul-Regalado.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

- Published16 November 2014

- Published27 August 2014

- Published27 August 2011