Here's Why Black People Have to Wait Twice as Long to Vote as Whites

Yes, minorities wait longer to vote -- but the widely disparaged voter ID laws in 2012 seem to have had fairly little to do with it.

On Election Day last year -- and over the weekend preceding it -- the airwaves were flooded with reports of endless lines at the polls, complete with photos of voters queued for hours, their faces a mixture of resolution and lifelessness. The pile-ups followed months of attempts by states across the country to pass restrictive voting laws -- lopping hours or days off the time when citizens could vote (sometimes with admittedly race-based intentions) or requiring voters to present IDs (sometimes with admittedly partisan intentions).

We know what happened: Minorities still turned out at record rates, and President Obama cruised to victory. But it wasn't clear whether those anecdotal stories sketched an accurate story, and to what extent the new laws (when allowed to stand) and lines had contributed -- until now. A paper by MIT's Charles Stewart digs into the data behind the anecdotes and finds that the affects of long lines are just as appallingly disparate as you might fear:

Viewed nationally, African Americans waited an average of 23 minutes to vote, compared to 12 minutes for whites; Hispanics waited 19 minutes. While there are other individual-level demographic difference present in the responses, none stands out as much as race.

What's impressive is how comparatively little variation there was in other demographic categories:

- The average wait time among those with household incomes less than $30,000 was 12 minutes versus 14 minutes for those with household incomes greater than $100,000.

- Strong Democrats waited an average of 16 minutes versus 11 minutes for strong Republicans.

- Respondents who said they paid close attention to the news waited 13.2 minutes; those who said they had little interest waited 12.8 minutes.

- Residents of the wealthiest ZIP codes (average household incomes of $50,000 and up) waited 13 minutes, versus 12 minutes for residents of the poorest ZIP codes ($30,000 and below).

Here's a crucial distinction: It ought to be self-evident that large disparities in the time required to vote between voters of different races are problematic for a nation that seeks equality for all. But the need to correct it doesn't necessarily prove that the system has a racist intent.

For example, longer lines correlate with urban areas, and so do black and Hispanic populations. It makes sense that any location with higher population density is going to have more logjams than a rural voting station. (Bolstering the point, individual white voters in racially diverse ZIP codes waited far longer in line than white voters in extremely Caucasian ZIP codes).

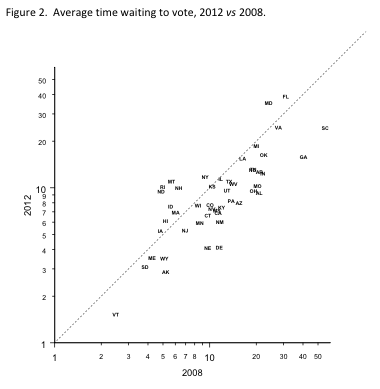

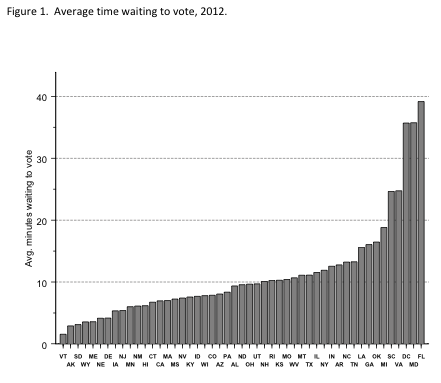

The data also suggests that whatever the problems with laws passed during the last election cycle, their biggest impact seems to be on the margin. States where wait times were long in 2008 tended to have long wait times in 2012, too, so the problems are of long standing:

In fact, Stewart found that the average vote time dropped by four minutes, to 13 minutes, between 2008 and 2012.

What about early voting? Well, early voters actually waited longer: 17.9 minutes on average, versus 12 minutes for Election Day voters. So while adding early voting might be a laudable effort, because it allows more people to vote more conveniently, it also won't necessarily decrease the disparity in wait times drastically. (There's a separate debate over whether early voting is actually a good thing; set that aside for now.)

Three takeaways:

- Stewart's paper makes a fairly convincing case that voting lines are a good place for would-be election reformers to look. Despite dire claims of rampant voter fraud that necessitates ID laws, alarmists have produced few real examples of fraud. Here, in contrast, is a documented problem.

- Given that there's a clear disparity but no direct causation in partisan chicanery, this might be a good place for bipartisan election reform, like the push President Obama has initiated, to begin.

- The Supreme Court is currently deliberating on the constitutionality of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which requires that certain jurisdictions with a history of racial prejudice in voting receive "preclearance" on any changes to voting laws. Those include South Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and most of Virginia.

While the justices appeared skeptical during oral arguments that the legacy of racism in those states remains strong enough to require preclearance, Stewart shows that those five states are in the top quintile for longest waits; and as we know, African-American voters wait longer than white ones. The justices' skepticism may have been misplaced.

Stewart ends on a pessimistic note, arguing that ideas about how to solve the problem are untested. Here are a few common-sense suggestions, however. And of course, eliminating old-fashioned incompetence among urban election officials would probably go a long way.

Hat tip: Taegan Goddard