The following is a bonus chapter from Anne Helen Petersen's Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema. You can read previous installments — on everyone from Katharine Hepburn to Marlon Brando — here.

In a December 1933 issue of New Movie Magazine, society reporter Grace Kingsley described her visit to screenwriter Donald Ogden Stewart’s famed costume party, where the who’s who of Hollywood showed up dressed, as the year’s theme dictated, as other Hollywood stars. The actress Fay Wray described the scene to Kingsley, cooing over each of her friend’s excellent costumes (“There’s Jack Gilbert as Lionel Barrymore in Rasputin!”) but really losing it when she sees “a little Chinese lady dancing about.”

But that lady wasn’t Chinese: She was the (white) comedienne Polly Moran. “I’m Anna May Wong!” she said, running over and brandishing her hands. “And my fingernails cost me a dollar and a half!”

As the picture that accompanied the article shows, Moran was decked out in full yellowface — including makeup to darken her skin, a wig, Chinese-style dress, and approximations of Wong’s signature long, pointed nails. In the picture, she makes a face intended to simulate a “Chinese” expression, and if you look closely, you can see that her eyes are taped up in an exaggeration of the Asian facial structure.

Moran, and whoever dressed her, would be familiar with this makeup technique (often achieved by using fish skin as an adhesive) because so many non-Asian women had been made up to play the role of Asian women. These were leading roles that could’ve been (but were seldom) given to classic Hollywood’s first and only Chinese-American star.

Anna May Wong, like other Hollywood actors of color, was not allowed in society, and would not have been invited to Stewart’s party. She couldn’t hang out with the very stars who exoticized and imitated her. In classic Hollywood, not only was it OK to act Asian, it was celebrated. And even though Stewart’s soiree was just a party, the behaviors modeled there bespoke the dominant understandings of Hollywood and America at large: White people can play at other races, and other races can play at very little.

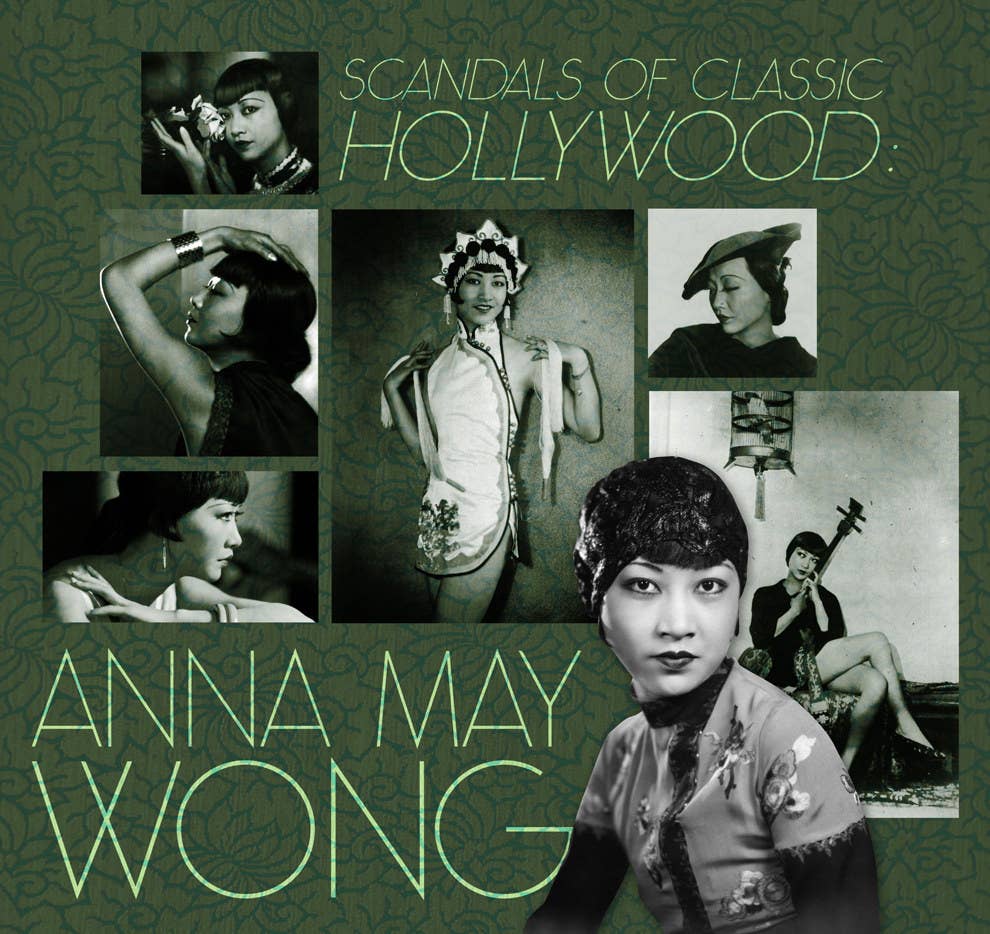

Anna May Wong never scandalized Hollywood with her string of fiancés, like Clara Bow, or an outré sex philosophy, like Mae West. Ultimately, the scandal of her career had little to do with her, or her actions — it’s the way that Hollywood, and the audience that powered it, remained so hideously stubborn about the roles a woman like her could play, both on and off the screen. Wong was a silent-film demi-star, a European phenomenon, a cultural ambassador, and a curiosity, the de facto embodiment of China, Asia, and the “Orient” at large for millions. She didn’t choose that role, but it became hers, and she labored, subtly, cleverly, persistently, to challenge what Americans thought an Asian or Asian-American should or could be — a challenge that persists today.

Wong was born in 1905 in Los Angeles, just off Flower Street on the outskirts of Chinatown. Fan-magazine renderings of Wong’s childhood didn’t shy from evoking the discrimination she faced, especially in her integrated elementary school. One boy would stick needles into her every day, to which she responded by simply wearing a thicker and thicker coat. A group of boys pulled her long braids, shoving her off the sidewalk and yelling, “Chink, Chink, Chinamen. Chink, Chink, Chinamen.” Sometimes the profile would admit that such children were of “lesser parents,” but the anecdotes were framed as a simple trial of childhood: no different than a white star getting teased as a child for an embarrassing name or pair of glasses.

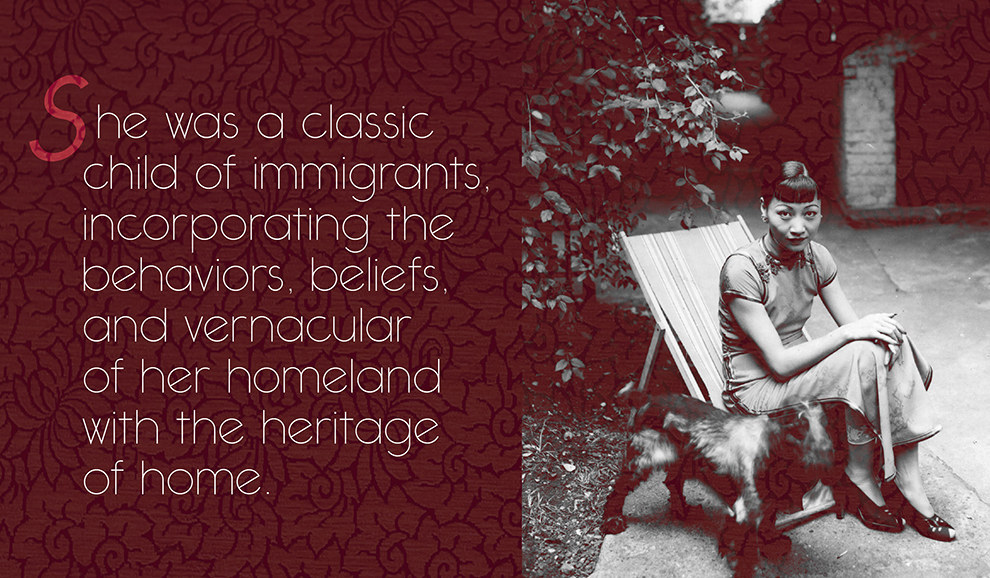

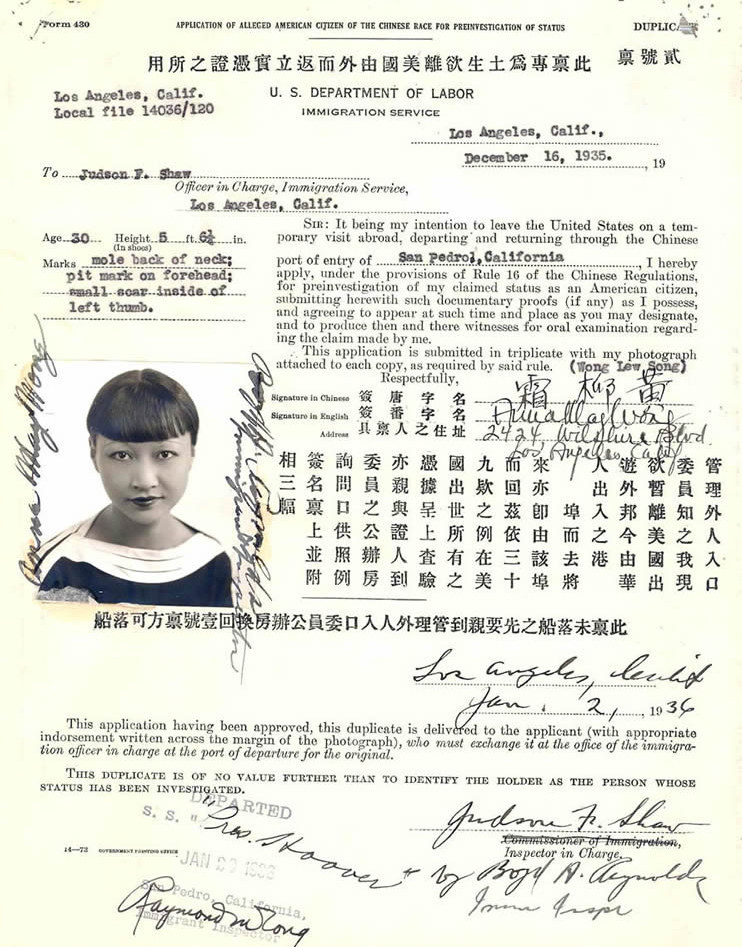

Profiles also labored to reconcile an identity that was at once wholly Chinese yet also American. She worked in a Chinese laundry, but that laundry wasn’t in Chinatown. Her parents forced her to go to Chinese school after American school, but she skipped it to go to the movies. She had a Chinese name (Wong Liu Tsong) that meant “Frosted Yellow Willows,” but she opted for the Americanized Anna May Wong. Her parents were skeptical of the moving image — her mother purportedly believed that cameras could steal a bit of the soul — but Wong eschewed Old World superstition. She was, in many ways, a classic child of immigrants, incorporating the behaviors, beliefs, and vernacular of her homeland with the heritage of home.

As Wong grew, she became increasingly fascinated with the Hollywood pictures that would film in Chinatown, which, in the late ‘10s and early ‘20s, studios would regularly use as a visual substitute for China — a conflation that made it even more difficult for Americans to understand that Chinese-Americans were a distinct culture from the Chinese.

To make Chinatown seem like the bustling streets of China, directors needed Chinese faces — which is how Wong first appeared, as an extra in Alla Nazimova’s The Red Lantern at the age of 14. She had asked for her father’s permission, but he was reluctant: As one profile explained, “Of course, many Chinese girls had played extra, but there are many Chinese girls who are not nice.” It was only after her father made sure that other “honorable” Chinese extras, all male, would guard her that he agreed to let her participate.

Over the next two years, Wong appeared in bit parts in various films, still attending school, before quitting in 1921 to focus full-time on her career. She was immediately cast in her first leading role in The Toll of the Sea, a nonoperatic take on Madame Butterfly that blew up the screen for two very simple reasons: It had Technicolor (two-strip, which meant only tones of reds and greens, but no matter, COLOR, that was sick), and Wong was actually a decent actress.

Wong’s acting was subtle and unmannered; her eyebrow game was on point. She had a piercing stare that made you feel as if she saw the very best and very worst things about you, and her signature blunt-cut bangs made her face seem at once exquisitely, perfectly symmetrical. Given the quilt work of exotic roles she’d played on the silent screen, audiences expected her to speak with a broken, accented, or otherwise un-American English. But her tone was refined, cool, cultured, like a slap in the face to anyone who’d assumed otherwise.

Her early success, like that of Japanese star Sessue Hayakawa, can at least partially be attributed to the global market for silent films. Yet to truly understand Anna May Wong’s unique place in Hollywood — and the particular type of racist role available to her — you have to understand both the rampant fetishization of the “Orient” by the West and the place of Chinese-Americans in California in the early 20th century.

In very broad terms, “Orientalism” refers to the overarching tendency of the “Occident,” or the Western world, to fetishize and exoticize the “Orient” (“The East,” or civilizations and cultures spanning the Asian continent). Scholar Graham Huggan defines exoticism as an experience that “posits the lure of difference while protecting its practitioners from close involvement” — and that’s exactly what Westerners wanted: a taste of “difference,” usually in the form of an evocative song, poem, or painting, without the actual immersive and possibly challenging experience thereof.

Mediated through the lens of Orientalism, members of distinct Asian, Middle Eastern, and African cultures are grouped together into one vast sultry and quasi-backward “Orient,” replete with heathens, pungent spices, snake charmers, mysticism, and all sorts of other offensively stereotypical renderings. For the Occident to reify its position as potent, masculine, and dominant, it had to figure the Orient as diffuse, feminized, and passive. It’s bullshit, but it pervaded everything from political speeches to children’s bedtime stories. Think Madame Butterfly, think the entire oeuvre of Rudyard Kipling, think "Rikki Tikki Tavi," think Aladdin.

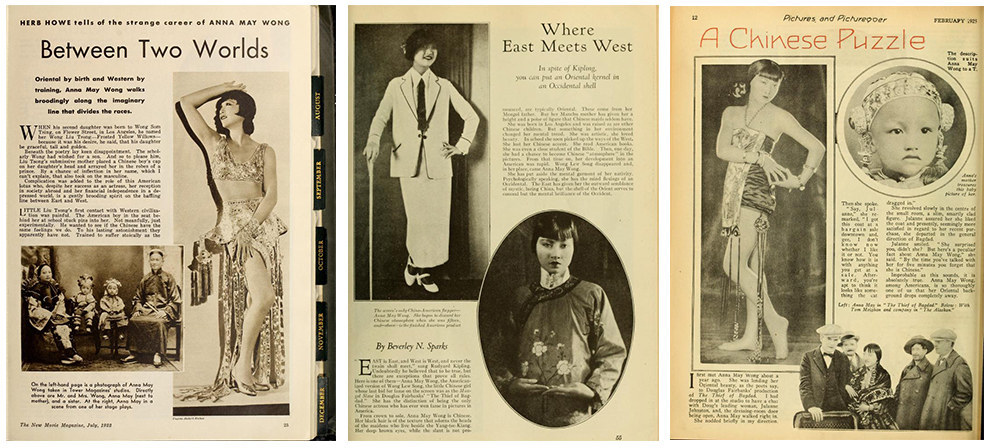

When Anna May Wong rose to stardom in the 1920s, the “great” empires of the West were in decline — but that simply made it all the more important to shore up the ideas and attitudes that were under threat. Which explains why every. single. article. I found about Anna May Wong somehow manages to sexualize and exoticize her while also placing her — her upbringing, her family, her heritage — in diametric opposition to “American” and Western practices.

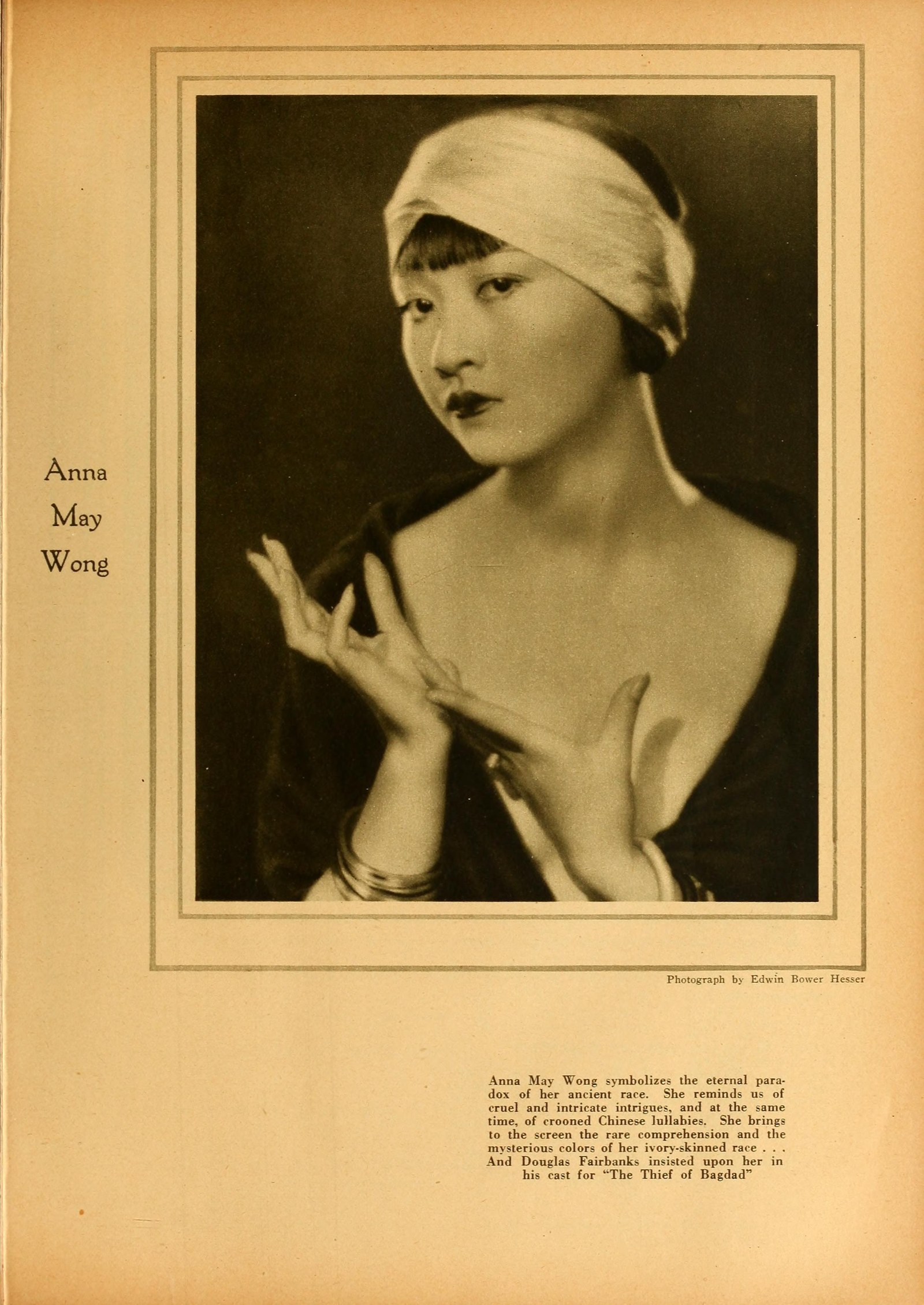

“Anna May Wong symbolizes the eternal paradox of her ancient race,” wrote one fan magazine. “She reminds us of cruel and intricate intrigues, and, at the same time, of crooned Chinese lullabies. She brings to the screen the rare comprehension and the mysterious colors of her ivory-skinned race.” That sort of rhetoric — directed to an almost entirely white audience — that’s Orientalism. That Wong was American, however, complicated the normal Orientalist discourses: She forced magazines to perform a lot of tricky rhetorical maneuvering where they acknowledged that she was somehow, magically, almost inconceivably, at once American and Chinese.

Wong was also opposite of what many had come to associate with Chinese-Americans, which, at least in the late 19th and early 20th century, comprised a subculture that was conceived of as being segregated, unknowable, and almost entirely male. The reasons for that reputation were complicated: When Chinese laborers first came to America in the mid-19th century, men traveled to make money, while women mostly stayed at home. With the passage of the Page Law in 1875, Chinese women with even a hint of “immoral character or suspect virtue” were banned from entering the United States, which resulted in even more gender imbalance.

Because Chinese lived in these nearly all-male configurations that didn’t match with American understandings of what community should look like, it was easy to further stigmatize and exclude them, both socially and legally. See, for example, the 1882 passage of the “Chinese Exclusion Act,” which prevented Chinese from entering the U.S. based on claims that as a people, the Chinese were immoral, unhealthy, and posed distinct threats to the American way of life and labor force (rhetoric that may sound familiar to anyone following contemporary immigration debates).

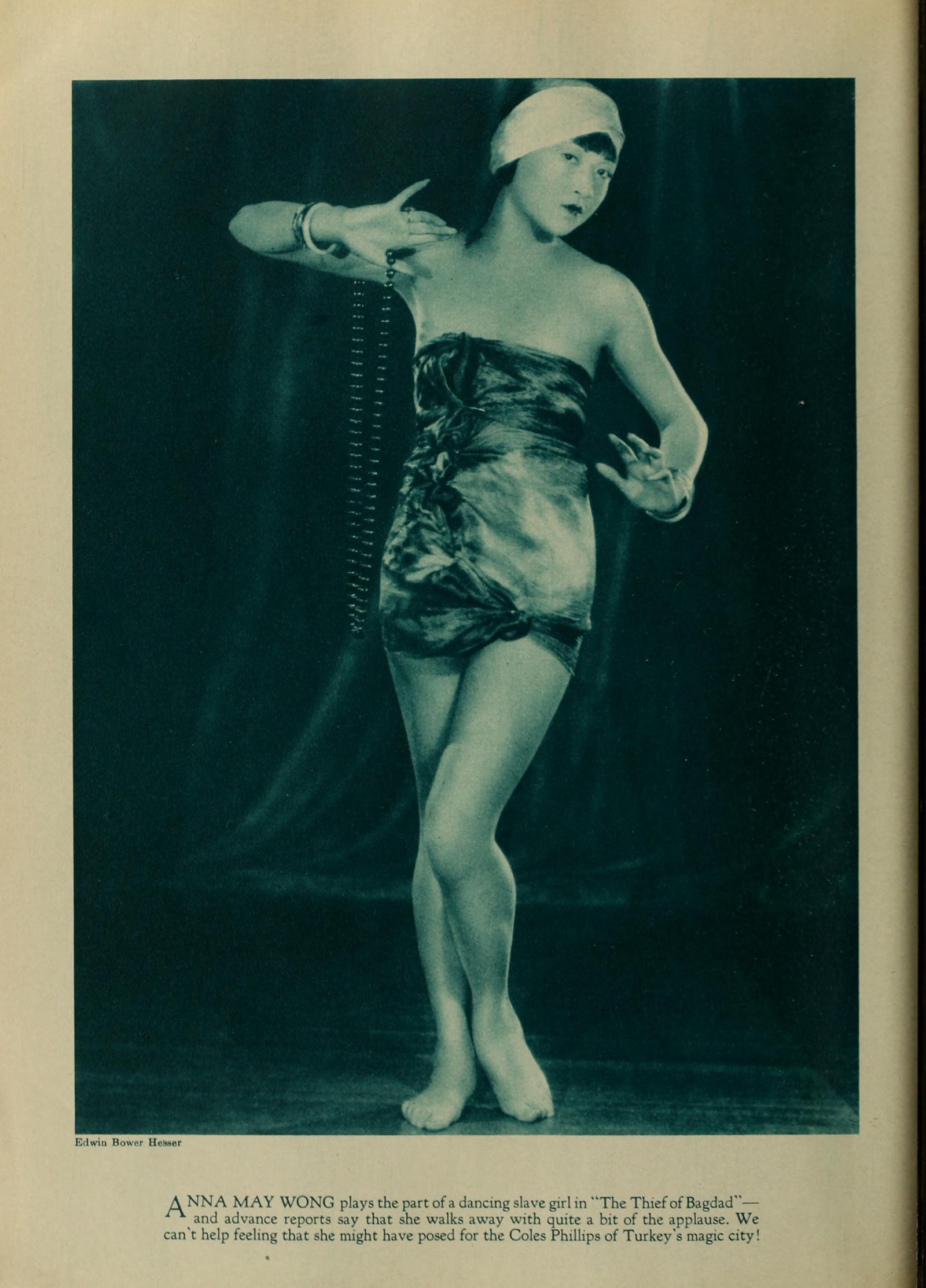

That was the environment of systemic racism in which Wong was operating in the early ‘20s, when her turn in the Technicolor Turn of the Sea was such a novelty that all of Hollywood saw it — including Douglas Fairbanks, then-ruling King of Hollywood, like Tom Cruise meets Brad Pitt only with a swashbuckling mustache. Fairbanks needed a dastardly “Mongol slave” for his production of The Thief of Baghdad, and immediately wanted Wong for the part.

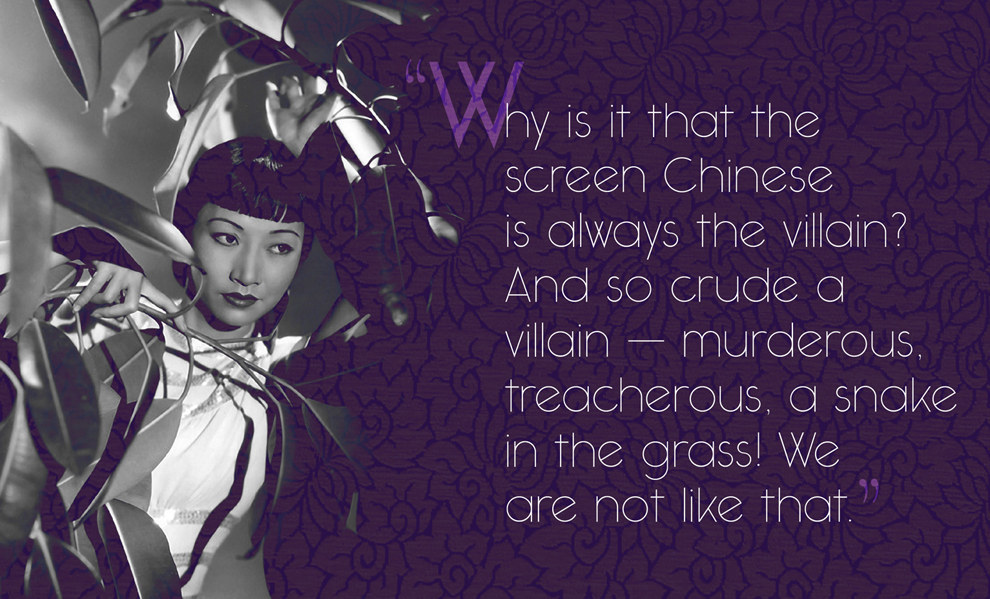

What do these two roles have in common? In one, Wong plays a Chinese “Lotus Flower” who falls for a white man who loves her but can’t possibly be with her; in the other she plays “the scheming handmaiden” who tries to prevent the love between the handsome, swashbuckling lead and his princess (the daughter of a caliph who is unaccountably white). So: a victim who can’t have love, or evil temptress who prevents a white woman from having love — these are the two roles that Wong would play again and again, with slight variations for ethnic specificity, time period, and plot, over the next two decades. A victim or a villain, with very little, in most cases, in terms of character development, ethnic specificity, or anything else to suggest that the depth, charisma, or worth of white counterparts.

Wong’s roles may have been shit, but the fan magazines loved her, unlike black actors, who were either relegated to even more demeaning bit parts and/or ghettoized in black films shown only in black theaters for black audiences. For various complicated reasons that have a lot to do with American racial history and the way that Orientalism actually weirdly celebrates the people and civilizations it fetishizes, it was OK for the fan mags to profile her, run pictures of her, and generally acquaint American audiences with her — but not put her on the cover.

In these profiles, you can see the press continuing, with extreme awkwardness, to reconcile the idea of a star who is at once American and Chinese:

To prove that she was Chinese:

From Crown to Sole, Anna May Wong is Chinese. Her black hair is of the texture that adorns the heads of the maidens who live beside the Yang-tse Kiang. Her deep brown eyes, while the slant is not pronounced, are typically Oriental.

But oh, wait, she’s totally American:

Improbable as this sounds, it is absolutely true. Anna May Wong, among Americans, is so thoroughly one of us that her Oriental background drops completely away.

No, seriously, guys, she’s Chinese:

She is as Chinese as kumquats and the lotus. ... She is of centuries ago and yet of today. ... Animation scarcely ever ruffles the tranquility of her round face.

NO, SERIOUSLY, SHE’S AMERICAN:

Anna May Wong has never even been to China, and you might just as well know it right now. Moreover, she has seen NY’s Chinatown only from a taxi-cab, and she doesn’t wear a mandarin coat … her English is faultless. Her conversation consists of scintillating chatter that any flapper might envy. Her sense of humor is thoroughly American. She didn’t eat rice when she and I lunched together, and she distinctly impressed it upon the waiter to bring her coffee, not tea.

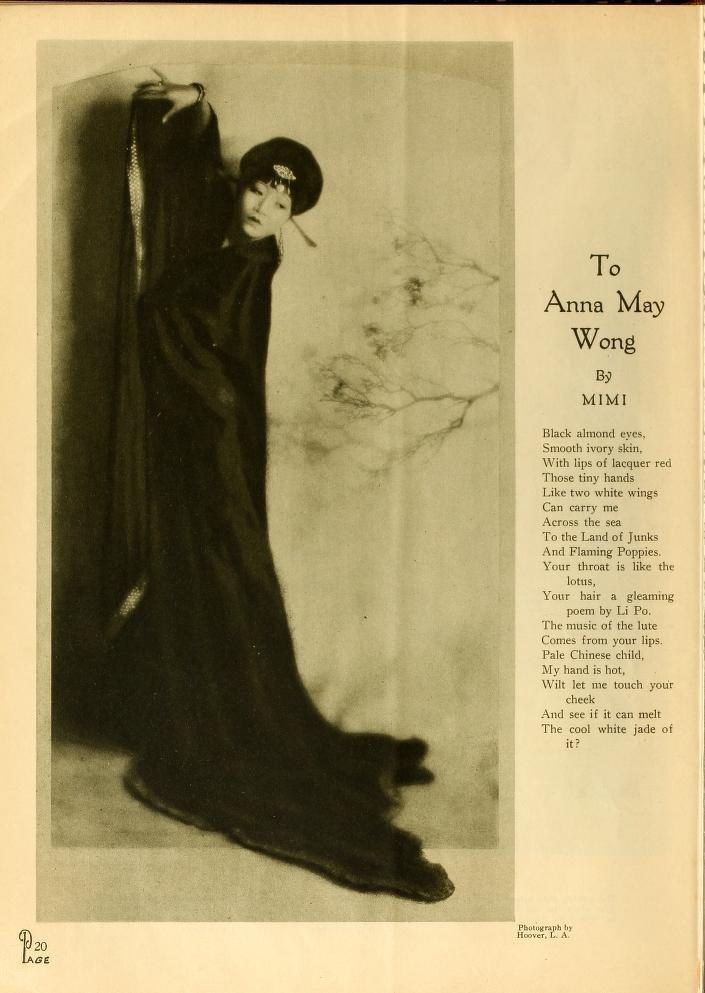

NEVER MIND, HERE’S A POEM, SHE’S TOTALLY CHINESE:

You can see how Wong would grow weary, both of this treatment in her publicity and the relative dearth of roles, especially complex ones, available to her. She was also understandably pissed that when an Asian role did come along, directors found an actor of basically any other ethnicity — Latino, Eastern European, Irish — to cast as the Asian character.

In 1928, when an opportunity came along to go to Europe, she jumped at it. There she could make films that might exoticize her slightly less. She’d be able to do things like hang out with her white co-stars. She'd maybe even be able to have a romance, which, to that point, had been wholly unavailable to her, at least publicly.

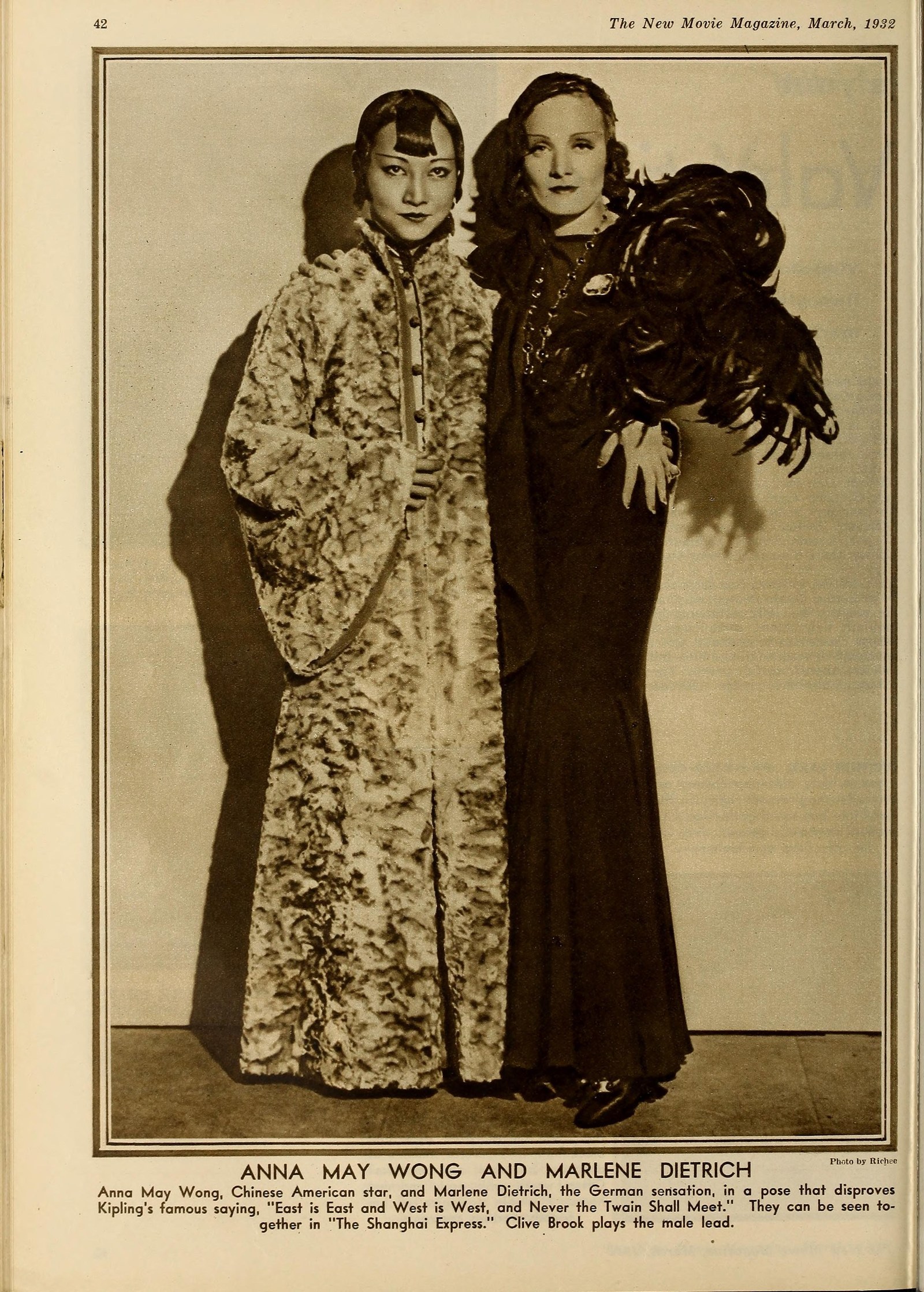

Making her home in Berlin, she not only got to star in all of her own films, but was celebrated as a great beauty. She hung out with Leni Riefenstahl; she palled around with Marlene Dietrich; she sparked a few vague sapphic whispers. She appeared in five British films, and while she didn’t get to kiss the white co-star, she did get a chance to shine, especially in Piccadilly (1929), her last silent film and widely believed to be her best performance.

Across Europe, Wong inspired very explicit adulation: Composer Constant Lambert wrote Eight Poems of Li Po and dedicated it to her; Eric Maschwitz wrote “These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)” to commemorate the end of a rumored romance. “They were all so wonderful to me,” Wong said upon her return to America. “You are admired abroad for your accomplishments and loved for yourself. That made me an individual, instead of a symbol of my race.” The extent to which Wong’s European films refused to make her a “symbol of her race” is questionable, but it’s certainly true that Wong, like Josephine Baker, Nella Larsen, and Langston Hughes, was celebrated in a way she had never experienced in America.

According to an American gossip columnist visiting Europe during Wong’s tenure, she was “acclaimed by nobility,” “the toast of the continent,” with “attendant stories of princes and even kings being madly in love with her.” This veneration was, at least in part, self-congratulatory: cultured Europeans’ way of showing just how much more sophisticated they were than those silly, racist Americans, even as they reproduced much of the same fetishizing rhetoric and narratives, just while letting the stars sit with them at dinner and waltzing cheek to cheek afterward.

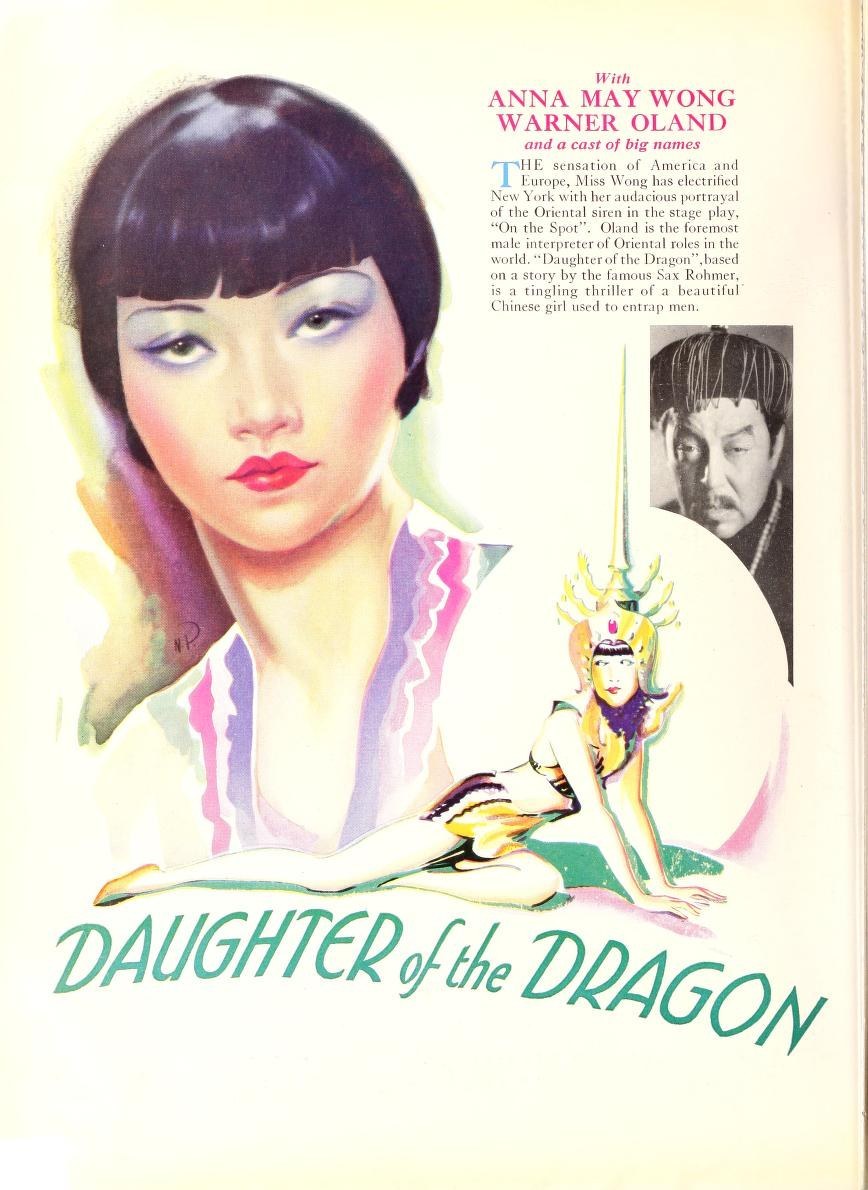

In 1931, Wong returned to Hollywood, lured by a contract from Paramount, which was busy scooping up European talent, and the promise of more substantial roles. She agreed to appear as a classic evil vamp in Daughter of the Dragon, but only because it meant that she’d then get a meaty part alongside Shanghai Express with Marlene Dietrich. To promote the film, Wong submitted to the studio’s attempt to further define her image by its exoticism. A January 1932 Picture Play profile titled "A Lone Lotus," for example, slathered the Orientalism on thick.

The cultured Oriental woman makes an ideal companion … Her meditative presence is restful to a man worn ragged by the American girl’s zest for parties and sports. Then she listens with flattering respect to her superior. The unfolding of her own intellectual development usually fascinates him with its surprises.

AND THEN (quoting Wong, supposedly):

“Usually, I am accorded greater chivalry than the American girls — because I let men serve me. They have told me, ‘Modern women are too efficient; they will not permit us to do things for them.' I have an inborn dependence upon man.”

BUT WAIT:

Her religion, embracing love and patience and service, is one that she has evolved from the mating of the old and the new. The rhythm of life, she calls it. "All good things work together for our benefit," she often says, "if we grant our 'Yeah, in holy meditation, shaped in a perfect syllable.'”

Here’s when, as readers more than 80 years after the fact, we have to ask ourselves: What the hell is going on? Who is coming up with this stuff? Would Wong actually say that? Can we attribute it, like so much of what was published in fan magazines, to her studio’s publicity department, trying to shape her star image into the Panda Express of Hollywood stars, right before the release of Shanghai Express?

Probably. Wong’s role in Express was, in many ways, a classic person-of-color best-friend role — only this best friend had an amazing resting bitchface and a gaze that could shut a man up with a single glance. Her true feat, of course, was getting people to look at something, anything, that wasn’t Dietrich’s intoxicating face for more than a minute. Plus, under the direction of Josef Sternberg, she got the most awesome German expressionist lighting of her life. Just look at her and Marlene. This is majesty.

A friendship with Dietrich, however, wasn’t the same as Dietrich-sized roles. Even though Shanghai Express was a success, meriting Best Picture and Best Director, that didn’t mean that there were necessarily parts for Wong. When MGM cast the leading female role of Lian Wha "Star Blossom," in The Son-Daughter, they claimed that Wong was “too Chinese” for the part, instead opting for LILY-WHITE WHITE AS THE DRIVEN SNOW WHITE LIKE DAD SOCKS WHITE Helen Hayes.

Hayes’ casting was but one of hundreds of instances of yellowface that, like blackface and redface, were wholly normalized in Hollywood at the time. Yellowface was everywhere: in movies, at costume parties, in the pages of fan magazines — for example, in the feature “Loretta [Young] Goes Oriental.”

Wong thus retreated to Europe, where she toured Britain and Scotland, made a few small film appearances (including one in which she got to kiss her white male lead), and generally resigned herself to living a more awesome life without the frustrations of Hollywood. In 1935, however, MGM began casting for its adaptation of Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth: a monster of a best-seller — we’re talking Dan Brown meets Harry Potter — and the winner of the 1932 Pulitzer Prize.

Buck had grown up in China as the child of missionaries, and her rendering of the Chinese experience, however imperfect, was nonetheless miles ahead in terms of complexity, sympathetic characters, and generalized rejection of the tropes that usually characterized white narratives of China. In short: It was the perfect Wong project.

Which is why she obviously didn’t get it.

Let’s recite the basics: MGM was making a high-profile movie set in China, depicting a Chinese family. A Chinese family in which both main leads are Chinese. There was one major Chinese actress in Hollywood — one who could also act. Which is why it makes TOTAL AND COMPLETE SENSE that MGM cast Paul Muni (Austrian) as the lead male and (the very German) Luise Rainer as the female lead.

MGM offered Wong the consolation prize of the role of Lotus, the slinky teahouse dancer who seduces the main moral character and becomes his second wife. But Wong refused. As she said, “You’re asking me — with Chinese blood — to do the only unsympathetic role in a picture featuring an all-American cast portraying Chinese characters.” She took MGM’s offer as an insult — which it unequivocally was.

Instead of returning to Europe, Wong decided that if she was “too Chinese,” she was going to own it by actually visiting China for the first time. At first, the Chinese press was antagonistic — rightfully angry at Hollywood’s depictions of China and the Chinese — and blamed Wong, who had appeared in so many of those texts, for enabling those depictions. But Wong acquitted herself well, acknowledging that a) China had every right to be mad about its depiction, b) she never had control of her roles, and was forced to play her characters in a certain way, and c) she was super tired of playing “sinister” types.

Touring the cities and countryside of China, Wong was a HUGE hit. As recollected in daily dispatches from The China Press, she came off as charming, beautiful, and the closest the Chinese, who lacked anything approximating a film industry, had to depictions of themselves on the screen, however warped.

By the time she returned to Hollywood in the late ‘30s, Wong’s disillusionment was increasingly difficult to mask. In interviews, she refused to hedge her criticisms of the industry, speaking frankly about her circumscribed American life: “I can’t treat a love affair lightly enough to discuss it,” she told one critic. “When I felt myself becoming fascinated, I put a stop to it before it became love.”

That is BRUTAL. But it was also the story of Wong’s life: At least, as she confessed years before, she could go in public with a man and no one would start placing them as a couple. “Life has special difficulties for the Oriental woman in the Western world,” she explained. “I sacrificed many fine friendships through fear that either the man or I might be hurt.”

Wong couldn’t be associated with a white man, and even if a man did risk falling in love with her, she knew that it would doom both her career and his...unless, of course, he was also Chinese. People wanted to talk to her about her love life constantly, but her rarefied position in Hollywood made it so the answer always had to be a lack, an absence, a solitude, a sadness. It’s no wonder that when asked about her idea of happiness, she claimed that it was “an island of solitude with books. Not material things — but wisdom.”

As Wong’s career faded over the course of the ‘40s and ‘50s, she was granted a semblance of that solitude. Like so many relics of the silent and classic era, she made appearances on early television, exploiting the most basic and exoticized components of her image. The only way to make audiences want to see an aging star, it seemed, was to evoke the facile characteristics of her image that had always irked her most.

In truth, Wong was never a star of the magnitude of the others previously featured in this series. Her story is worth telling, however, not because of the magnitude of her stardom, but for its smallness — studying the inability of Hollywood to make use of a star of her potential says just as much about Hollywood and the fan base that fueled it as examining the stars that dominated it.

And yet, how much has changed over the last 80 years? It’s only been in the last decade, give or take, that Asian characters have begun regularly showing up in mainstream television and film, whether in “blindcasted” shows like Grey’s Anatomy (Sandra Oh as Cristina Wang), characters involved in actual romance (Daniel Dae Kim as Jin-So Kwan and Yunjin Kim as Sun-Hwa Kwon in Lost), and even those permitted to make out with/love characters who aren’t also Asian: Cho Chang (Katie Leung) in Harry Potter, Lane Kim (Keiko Agena) in Gilmore Girls, Han (Sun King) in the Fast and Furious franchise, Emily Fields (Shay Mitchell) in Pretty Little Liars. Today there's more work for Asian actors — notably, on channels like The CW, which is cultivating and catering to mostly teens and other niche audiences. This season’s crop of new shows also includes plume roles for John Cho (Selfie) and an almost entirely Asian cast in Fresh Off the Boat; time will tell how they fare.

But even with China posed to become the primary source of film revenue over the next 10 years, it’s startling to realize just how persistent and pernicious the stereotyping remains. In action cinema, the Asian male protagonist only gets to hug where his white counterpart would get a fuck; in films as various as The Hangover and Pitch Perfect, Asian characters become cutout punch lines, incredibly offensive clichés played for cheap laughs. Lucy Liu is arguably the only mainstream Asian star in Hollywood, and her roles have been relegated to voicing animated characters in Kung Fu Panda and playing the female version of Watson in CBS’s Sherlock Holmes adaptation, Elementary.

Wong, along with Dorothy Dandridge, Dolores Del Rio, Lupe Velez, Sessue Hayakawa, Paul Robeson, and Bo Jangles, are celebrated as trailblazers: the ones who did all the hard, often demeaning labor so that those who came after them would be able to walk the path to stardom free and clear. The scandal of contemporary Hollywood, then, is that every would-be star of color must seemingly blaze that path again, fighting a seemingly endless battle against the generalized racial logic that continues to guide so much of the industry.

Buy Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema.