Marguerite Evans-Galea hadn’t finished telling her boss she was pregnant, before he told her to finish up.

It was 2000 and Evans-Galea was doing her postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Utah. The news of her first pregnancy ended her career at the teaching hospital.

“I was let go from that position when I told them that I was pregnant. I told my boss the news and was very excited, and he followed up straight away with: “We’ll finish you up now.” It was literally in the same conversation – I felt like I’d been slapped in the face.”

Even though he called her at 6am on the following Saturday morning to apologise, Evans-Galea took legal advice and left.

And although Evans-Galea is unsure if a similar situation would be tolerated now, she says women in science are edged out in more subtle ways.

“There are instances of people who would leave a group on maternity leave and you never see them again. It might be that they are told: “Sorry we don’t have funding for you.”

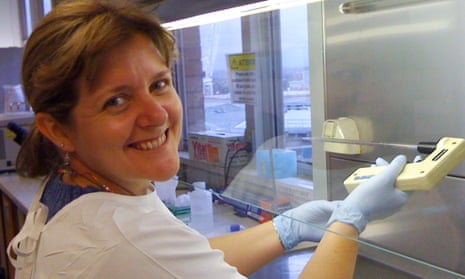

Marguerite Evans-Galea is now based in Melbourne at the Murdoch Childrens Research Centre, where she leads international collaborations researching and developing cell and gene therapies for Friedreich ataxia.

Brigid Delaney: Could you tell me about your work with Friedreich ataxia?

Marguerite Evans-Galea: Friedreich ataxia is a disease that typically begins at the age of 10. Parents will notice their child stumbling, then they will go to neurologists and have tests. It’s a progressive disease. Individuals lose their coordination and will eventually require a wheelchair. In adulthood, they also develop heart disease. Lifespan is shortened to 37.

When I was at the University of Utah I was working with yeast, and I was struggling as a scientist to connect my research with people. I had a strong need for my research to matter. Friedreich ataxia was connected to the work I was doing with yeast in the lab. When I came back to Australia, I was able to work with a clinical team. It’s been so exciting. The FXN gene was first discovered in the 90s, and there are potential treatments in development. Since then, it has become like a puzzle I couldn’t put down.

BD: How family-friendly is science?

M E-G: For workers with young children, Walter & Eliza Hall [Institute of Medical Research] has introduced a family room, providing childcare that is competitive, breastfeeding rooms and extra funding to pay for someone to travel with your child while you go to a conference or a grant review panel. These things are important because you need to be in at work – you can’t do experiments from home.

BD: What are the factors that make flexible work for women (and men) difficult in your area?

M E-G: There are a few overarching aspects. Career disruption due to taking leave and having children[and] the boys club culture in science. This is very common across many industries. Here [Murdoch Childrens Research Institute] we don’t see it quite so much. There’s a majority female workforce, with a female CEO but many women are in lower positions.

Secondly, unconscious bias. Monash University has started training its leadership team in unconscious bias, [how they may be] looking at favouring men to do certain tasks or take up leadership opportunities.

Thirdly, the merits with which we measure track record. In academic science, there is a heavy push on publications and grants. You have to be publishing often, and that may not suit scientists with young families or other responsibilities.

We have to look at the kind of attributes we want in our scientists. If you ask a year seven student to draw a scientist, they’ll draw a balding male in a lab coat. We have to change the face of what we perceive a scientist to be. The opportunities are not always presented to women and there’s a lack of confidence. We are trying to increase the visibility.

BD: Have you ever been encouraged to modify behaviour in masculine environments?

M E-G: When I was doing my PhD at theUniversity of New South Wales, I was a vibrant, outspoken twenty something and I was taken aside by a senior male. I was told to tone it down, to calm down.

I was being passionate and excited, and had great ideas that I was hoping to be heard. That conversation stayed with me. There have been other instances where something has been said. But I feel like now I can be myself . I still have a professional demeanour but I have more confidence in my strengths and weaknesses. I’m much more comfortable in my own skin.

BD: You are active on Twitter. Can you tell me the role social media plays in your work?

M E-G: In my area, Twitter is a growing thing for women to connect on. I don’t know if it’s anecdotal but there are a lot of female scientists on Twitter, and it’s brought together a lot of us who work in science. Someone at a conference tweets “I’m here”, and then you have a meet up. It’s really positive.

BD: Twitter can get ugly though. Is that the case for scientists?

M E-G: Collegial discussion is common in science[and] it’s extremely rare for things to get ugly on social media. Scientists are good at challenging each other in our thinking and correcting each other and ourselves when we are wrong – it’s part of science training and our industry.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion