Shortly after 3 p.m. on Friday, May 1, Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao weighed in for their historic encounter that would be contested the following night at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas. Later on Friday afternoon, collection agents for the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), which had been contracted to oversee drug testing for the Mayweather-Pacquiao fight, went to Mayweather’s Las Vegas home to conduct a random unannounced drug test.

The collection agents found evidence of an IV being administered to Mayweather. Bob Bennett, the executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission, which had jurisdiction over the fight, says that USADA did not tell the commission whether the IV was actually being administered when the agents arrived. USADA did later advise the NSAC that Mayweather’s medical team told its agents that the IV was administered to address concerns related to dehydration.

Mayweather’s medical team also told the collection agents that the IV consisted of two separate mixes. The first was a mixture of 250 milliliters of saline and multi-vitamins. The second was a 500-milliliter mixture of saline and Vitamin C. Seven hundred and fifty milliliters equals 25.361 ounces, an amount equal to roughly 16 percent of the blood normally present in an average adult male.

The mixes themselves are not prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), which sets the standards that USADA purports to follow. However, their intravenous administration is prohibited by WADA.

More specifically, the 2015 WADA “Prohibited Substances and Methods List” states, “Intravenous infusions and/or injections of more than 50 ml per 6 hour period are prohibited except for those legitimately received in the course of hospital admissions, surgical procedures, or clinical investigations.”

This prohibition is in effect at all times that the athlete is subject to testing. It exists because, in addition to being administered for the purpose of adding specific substances to a person’s body, an IV infusion can dilute or mask the presence of another substance that is already in the recipient’s system or might be added to it in the near future.

What happened next with regard to Mayweather is extremely troubling.

The first fighter of note to test positive for steroids after a professional championship fight was Frans Botha, who decisioned Axel Schulz in Germany to win the vacant International Boxing Federation heavyweight crown in 1995 but was stripped of the title by the IBF after a urine test indicated the use of anabolic steroids.

It’s a matter of record that, since then, Fernando Vargas (stanozolol), Lamont Peterson (an unspecified anabolic steroid), Andre Berto (norandrosterone), Antonio Tarver (drostanolone), Roy Jones (an unspecified anabolic steroid), James Toney (nandrolone, boldenone metabolite, and stanozolol metabolite), Brandon Rios (methylhexaneamine), Erik Morales (clenbuterol), Richard Hall (an unspecified anabolic steroid), Cruz Carbajal (nandrolone and hydrochlorothiazide), Orlando Salido (nandrolone), and Tony Thompson (hydrochlorothiazide) are among the fighters who have tested positive for the presence of a prohibited performance enhancing drug or masking agent in their system.

Almost always, fighters who test positive express disbelief and maintain that the prohibited substance was ingested without their knowledge. In most instances, punishment has been minimal or there has been no punishment at all.

Other fighters like former heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield, Shane Mosley (who won belts in three different weight classes), and heavyweight contender Jameel McCline, did not test positive but were named in conjunction with PED investigations conducted by federal law enforcement authorities.

By way of example, on August 29, 2006, federal Drug Enforcement Agency officials in Alabama raided a compounding pharmacy (a pharmacy that makes its own drugs generically) called Applied Pharmacy Services. The documents seized included records revealing that a patient named “Evan Fields” picked up three vials of testosterone and related injection supplies from a doctor in Columbus, Georgia in June 2004. That same month, Fields received five vials of a human growth hormone called Saizen. The documents further revealed that, in September 2004, Fields underwent treatment for hypogonadism (a condition in which the body does not produce enough natural testosterone, often a consequence of the use of performance enhancing drugs). The home address, telephone number, and date of birth listed for Evan Fields in Applied Pharmacy’s records were identical to those of Evander Holyfield.

Similarly, Shane Mosley never tested positive for illegal performance enhancing drugs. But his testimony before a grand jury investigating the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative (BALCO) made it clear that he used prohibited PEDs prior to his 2003 victory over Oscar De La Hoya.

Many types of PED use are prohibited in boxing and other sports because of health concerns and the fact that they give athletes an unfair competitive advantage. Their use also often violates federal laws regarding controlled substances. But PED use is more prevalent in boxing today than ever before, particularly at the elite level. Some conditioning coaches have well-known reputations for shady tactics. In many gyms, there is a person on site who serves as a pipeline to PED suppliers.

Indeed, for many fighters, the prevailing ethic seems to be, “If you’re not cheating, you’re not trying.” In a clean world, fighters don’t get older, heavier, and faster at the same time. But that’s what’s happening in boxing. Fighters are reconfiguring their bodies and, in some instances, look like totally different physical beings. Improved performances at an advanced age are becoming common. Fighters at age 35 are outperforming what they could do when they were thirty. In some instances, fighters are starting to perform at an elite level at an age when they would normally be expected to be on a downward slide.

Victor Conte was the founder and president of BALCO and at the vortex of several well-publicized PED scandals. He spent four months in prison after pleading guilty to illegal steroid distribution and tax fraud in 2005. Since then, Conte has undergone a remarkable transformation and is now a forceful advocate for clean sport. What makes him a particularly valuable asset is his knowledge of how the performance enhancing drugs game was - and is - played. Indeed, former federal prosecutor Jeff Novitzky, who was instrumental in putting Conte behind bars, acknowledged in a recent interview on “The Joe Rogan Experience” that Conte now has “an anti-doping platform” and has come “over to the good side.”

“The use of performance enhancing drugs is rampant in boxing, particularly at the elite level,” Conte recently told this writer. “If there was serious testing and the fighters believed that the testing was effective, they’d be less inclined to use prohibited drugs. But almost across the board, state athletic commissions have minimal expertise, limited funding, and little or no will to address the problem. So knowing that the testing programs are inept, many fighters feel that they’re forced to use these drugs to compete on a level playing field.”

In recent years, the United States Anti-Doping Agency has stepped into the enforcement void.

USADA was created in 1999 pursuant to the recommendation of a United States Olympic Committee task force that recognized the need for credible PED testing of all Olympic and Paralympic athletes representing the United States.

Despite its name, USADA is neither a government agency nor part of the United States Olympic Committee. It is an independent “not-for-profit” corporation headquartered in Colorado Springs that offers drug-testing services for a fee. Most notably, the United States Olympic and Paralympic movement utilize its services. Because of this role, USADA receives approximately $10 million annually in Congressional funding, more in Olympic years.

USADA’s website states, “The organization continues to aspire to be a leader in the global anti-doping community in order to protect the rights of clean athletes and the integrity of competition around the world. We hold ourselves to the same high standards exhibited by athletes who fully embrace true sport. We commit to the following core values to guide our decisions and behaviors.” The core values listed are integrity, respect, teamwork, responsibility, and courage.

Travis Tygart, the chief executive officer of USADA, has spearheaded the organization’s expansion into professional boxing. That opportunity initially arose in late 2009, when drug testing became an issue in the first round of negotiations for a proposed fight between Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao. When those negotiations fell through, Mayweather opted instead for a May 1, 2010, bout against Shane Mosley.

During a March 18, 2010, conference call to promote Mayweather-Mosley, Tygart advised the media, “Both athletes have agreed to USADA’s testing protocols, including blood and urine testing, which is unannounced, which is anywhere and anytime. There is no limit to the number of tests that we can complete on these boxers.”

Thereafter, Tygart moved aggressively to expand USADA’s footprint in boxing and forged a working relationship with Richard Schaefer, who until 2014 served as CEO of Golden Boy Promotions, one of boxing’s most influential promoters. USADA also became the drug-testing agency of choice for fighters advised by Al Haymon, who is now the most powerful person in boxing. In addition to representing Mayweather, Haymon is the driving force behind Premier Boxing Champions. He has bought time on CBS, NBC, ESPN, Spike, and several other networks to showcase his product. Most boxing matches televised by Showtime also feature Haymon fighters.

Drug testing, if it is to inspire confidence, should be largely transparent. Much of USADA’s operation insofar as boxing is concerned is shrouded in secrecy. Sometimes there’s an announcement when USADA oversees drug testing for a fight. Other times, there is not. The organization has resisted filing its boxer drug-testing contracts with governing state athletic commissions. On several occasions, New York and Nevada have forced the issue. Compliance has often been slow in coming.

When asked to identify the boxing matches for which a USADA drug-testing contract was filed with either the New York or Nevada State Athletic Commissions, Travis Tygart declined through a spokesperson (USADA senior communications manager Annie Skinner) to answer the question.

USADA’s fee structure (which USADA has endeavored to shield from public view) has also raised eyebrows.

The primary alternative to USADA insofar as PED testing for boxers is concerned is the Voluntary Anti-Doping Association (VADA). Like USADA, VADA’s testing laboratories are accredited by the World Anti-Doping Agency and it uses internationally recognized collection agencies. Unlike USADA, VADA utilizes carbon isotope ratio (CIR) testing on every urine sample it collects from a boxer. USADA often declines to administer CIR testing on grounds that it’s unnecessary and too expensive. Of course, the less expensive that tests are to administer, the better it is for USADA’s bottom line.

VADA charged a total of $16,000 to administer drug testing for the April 18, 2015, junior-welterweight fight between Ruslan Provodnikov and Lucas Matthysse. By contrast, USADA charged $36,000 to administer drug testing for the April 11, 2015, middleweight encounter between Andy Lee and Peter Quillin.

The Lee-Quillin bout was part of Al Haymon’s Premier Boxing Champions series. USADA is often paid quite generously for services rendered in conjunction with fights in which Haymon plays a role.

A notable example is the fee paid to USADA for administering drug testing in conjunction with the May 2, 2015, Mayweather-Pacquiao fight. Haymon advises Mayweather, and Team Mayweather controlled the promotion. USADA’s contract called for it to receive an up-front payment of $150,000 to test Mayweather and Pacquiao.

More troubling than USADA’s fee structure are the accommodations that it seems to have made for clients who either pay more for its services or use USADA on a regular basis. The case of Erik Morales, who has held world titles in three weight divisions, is an example.

Under standard sports drug testing protocols, when blood or urine is taken from an athlete, it is divided into an “A” and “B” sample. The “A” sample is tested first. If it tests negative, end of story; the athlete has tested “clean.” If, however, the “A” sample tests positive, the athlete has the right to demand that the “B” sample be tested. If the “B” sample tests negative, the athlete is presumed to be clean. But if the “B” sample also tests positive, the first positive finding is confirmed and the athlete then has a problem.

In 2012, Erik Morales was promoted by Golden Boy, which, as earlier noted, was under the leadership of Richard Schaefer. Golden Boy was the lead promoter for an Oct. 20 fight card at Barclays Center in Brooklyn that was to be headlined by Morales vs Danny Garcia.

On Thursday, Oct. 18, 2012, the website Halestorm Sports reported that Morales had tested positive for a banned substance. Thereafter, Golden Boy and USADA engaged in damage control.

Dan Rafael of ESPN.com spoke with two sources and wrote, “The reason the fight has not been called off, according to one of the sources, is because Morales’ ‘A’ sample tested positive but the results of the ‘B’ sample test likely won’t be available until after the fight. ‘[USADA] said it could be a false positive,’ one of the sources with knowledge of the disclosure said.”

Richard Schaefer told Chris Mannix of SI.com, “USADA has now started the process. The process will play out. There is not going to be a rush to judgment. Morales is a legendary fighter. And really, nobody deserves a rush to judgment. You are innocent until proven guilty.”

Then, on Friday, one day before the scheduled fight, Keith Idec revealed on Boxing Scene that samples had been taken from Morales on at least three occasions. Final test results from the samples taken on Oct. 17 were not in yet. But both the “A” and “B” samples taken from Morales on Oct. 3 and Oct. 10 had tested positive for clenbuterol. In other words, Morales had tested positive for clenbuterol four times.

Clenbuterol, a therapeutic drug first developed for people with breathing disorders such as asthma, is widely used by bodybuilders and athletes. It helps the body increase its metabolism and process the conversion of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into useful energy. It also boosts muscle growth and eliminates excess fats caused by the use of certain steroids. Its therapeutic use is banned in the United States, as is its use in animals raised for human consumption. It is also banned by WADA.

Under the WADA prohibited list, no amount of clenbuterol is allowed in a competitor’s body. The measure is qualitative, not quantitative. Either clenbuterol is there or it is not.

According to a report in the New York Daily News, after Morales was confronted with the positive test results, he claimed a USADA official suggested that he might have inadvertently ingested clenbuterol by eating contaminated meat. Meanwhile, the New York State Athletic Commission issued a statement referencing a representation by Morales that he “unintentionally ingested contaminated food.”

However, no evidence was offered in support of the contention that Morales had ingested contaminated meat.

Nor was any explanation forthcoming as to why USADA kept taking samples from Morales after four tests (two “A” samples and two “B” samples from separate collections) came back positive. Giving Morales these additional tests was akin to giving someone who has been arrested for driving while intoxicated a second and third blood test a week after the arrest.

The moment that the “B” sample from Morales’ first test came back positive, standard testing protocol dictated that this information be forwarded to the New York State Athletic Commission. But neither USADA nor Richard Schaefer did so in a timely manner. Rather, it appears as though the commission and the public may have been deliberately misled in regard to the testing and how many tests Morales had failed.

New York State Athletic Commission sources say that the first notice the NYSAC received regarding Morales’ test results came in a three-way telephone conversation with representatives of Golden Boy and USADA after the story broke on Halestorm Sports. In that conversation, the commission was told that there were “some questionable test results” for Morales but that testing of Morales’ “B” sample would not be available until after the fight.

Travis Tygart has since said, “The licensing body was aware of the positive test prior to the fight. What they did with it was their call.”

That’s terribly misleading.

This writer submitted a request for information to the New York State Athletic Commission asking whether it was advised that Erik Morales had tested positive for Clenbuterol prior to the Oct. 18, 2012, revelation on Halestorm Sports.

On Aug. 10, 2015, Laz Benitez (a spokesperson for the New York State Department of State, which oversees the NYSAC) advised in writing, “There is no indication in the Commission’s files that it was notified of this matter prior to October 18, 2012.”

The Garcia-Morales fight was allowed to proceed on Oct. 20, in part because the NYSAC did not know of Morales’ test history until it was too late for the commission to fully consider the evidence and make a decision to stop the fight. Since then, people in the PED-testing community have begun to openly question the role played in boxing by USADA. What good are tests if the results are not properly reported?

Don Catlin founded the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory in 1982 and is one of the founders of modern drug testing in sports. Three years ago, Catlin told this writer, “USADA should not enter into a contract that doesn’t call for it to report positive test results to the appropriate governing body. If it’s true that USADA reported the results [in the Morales case] to Golden Boy and not to the governing state athletic commission, that’s a recipe for deception.”

When asked about the possibility of withholding notification because of inadvertent use (such as eating contaminated meat), Catlin declared, “No! The International Olympic Committee allowed for those waivers 25 years ago, and it didn’t work. An athlete takes a steroid, tests positive, and then claims it was inadvertent. No one says, ‘I was cheating. You caught me.’”

Victor Conte is in accord and says, “The Erik Morales case was a travesty. If you’re doing honest testing, you don’t have a positive “A” and “B” sample and then another positive “A” and “B” sample and keep going until you get a negative result.”

In the absence of a credible explanation for what happened or an acknowledgement by USADA that there was wrongdoing that will not be repeated, the Erik Morales matter casts a pall over USADA.

The way things stand now, how can any of USADA’s testing in any sport be trusted by the sports establishment or the public? Would USADA handle the testing of an Olympic athlete the way it handled the testing of Erik Morales?

That brings us to Floyd Mayweather and USADA.

Mayweather has gone to great lengths to propagate the notion that he is in the forefront of PED testing to “clean up” boxing. Beginning with his 2010 fight against Shane Mosley, he has mandated that he and his opponent be subjected to what he calls “Olympic-style testing” by USADA.

At a media “roundtable” in New York before the June 24, 2013, kick-off press conference for Mayweather vs. Canelo Alvarez, Mayweather Promotions CEO Leonard Ellerbe declared, “We’ve put in place a mechanism where all Mayweather Promotions fighters will do mandatory blood and urine testing 365-24-7 by USADA.”

But neither Mayweather nor the fighters that Mayweather Promotions has under contract have undergone 365-24-7 testing - tests that can be administered any place at any time and would make it more risky for an athlete to use prohibited PEDs.

Drug testing for a Mayweather fight generally begins shortly after the fight is announced. Mayweather and his opponent agree to keep USADA advised as to their whereabouts at all times and submit to an unlimited number of unannounced blood and urine tests. That sounds good. But in effect, USADA allows Mayweather to determine when the testing begins. That leaves a long period of time during which there are no checks on what substances he might put into his body.

For example, Mayweather didn’t announce Andre Berto as the opponent for his upcoming Sept. 12 fight until Aug. 4, only 39 days before the fight. That didn’t leave much time for serious drug testing. From the conclusion of the Pacquiao fight until the Berto announcement, Mayweather was not subject to USADA testing.

Here, the thoughts of Victor Conte are instructive.

“Mayweather is not doing ‘Olympic-style testing,’” Conte states. “Olympic testing means that you can be tested twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year. If USADA was serious about boxing becoming a clean sport, it would say, ‘We don’t do one-offs. If you sign up for USADA testing, we reserve the right to test you at any time 365-24-7.’ But that’s not what USADA does with Mayweather or any other fighter that I know of.”

“The benefits that an athlete retains from using anabolic steroids and certain other PEDs carry over for months,” Conte continues. “Anybody who knows anything about the way these drugs work knows that you don’t perform at your best when you’re actually on the drugs. You get maximum benefit after the use stops. I can’t tell you what Floyd Mayweather is and isn’t doing. What he could be doing is this. The fight is over. First, he uses these drugs for tissue repair. Then he can stay on them until he announces his next fight, at which time he’s the one who decides when the next round of testing starts. And by the time testing starts, the drugs have cleared his system.

“Do I know that’s what’s happening? No, I don’t. I do know that the testing period for Mayweather’s fights is getting shorter and shorter. What is it for this one? Five weeks? The whole concept of one man dictating the testing schedule is wrong. But USADA lets Mayweather do it. USADA is not doing effective comprehensive testing on Floyd Mayweather. Testing for four or five weeks before a fight is nonsense.”

As noted earlier, USADA CEO Travis Tygart declined to be interviewed for this article. Instead, senior communications manager Annie Skinner emailed a statement to this writer that outlines USADA’s mission and reads in part, “Just like for our Olympic athletes, any pro-boxing program follows WADA’s international standards, including: the Prohibited List, the International Standard for Testing & Investigations (ISTI), the International Standard for Therapeutic Use Exemptions (ISTUEs) and the International Standards for Protection of Privacy and Personal Information (ISPPPI).”

Skinner’s statement is incorrect. This writer has obtained a copy of the contract entered into between USADA, Floyd Mayweather, and Manny Pacquiao for drug testing in conjunction with Mayweather-Pacquiao. A copy of the entire contract can be found here.

Paragraph 30 of the contract states, “If any rule or regulation whatsoever incorporated or referenced herein conflicts in any respect with the terms of this Agreement, this Agreement shall in all such respects control. Such rules and regulations include, but are not limited to: the Code [the World Anti-Doping Code]; the USADA Protocol; the WADA Prohibited List; the ISTUE [WADA International Standard for Therapeutic Use Exemptions]; and the ISTI [WADA International Standard for Testing and Investigations].”

In other words, USADA was not bound by the drug testing protocols that one might have expected it to follow in conjunction with Mayweather-Pacquiao. And this divergence was significant vis-a-vis its rulings with regard to the IV that was administered to Mayweather on May 1.

In evaluating USADA’s conduct with regard to Mayweather’s IV, the evolution of the USADA-Mayweather-Pacquiao contract is important.

It was announced publicly that the bout contract Mayweather and Pacquiao signed in February 2015 to fight each other provided that drug testing would be conducted by USADA. But the actual contract with USADA remained to be negotiated. In early March, USADA presented the Pacquiao camp with a contract that allowed the testing agency to grant a retroactive therapeutic use exemption (TUE) to either fighter in the event that the fighter tested positive for a prohibited drug. That retroactive exemption could have been granted without notifying the Nevada State Athletic Commission or the opposing fighter’s camp.

Team Pacquiao thought that was outrageous and an opportunity for Mayweather to game the system. Pacquiao refused to sign the contract.

Thereafter, Mayweather and USADA agreed to mutual notification and the limitation of retroactive therapeutic use exemptions to narrowly delineated circumstances. With regard to notice, a copy of the final USADA-Mayweather-Pacquiao contract provides: “Mayweather and Pacquiao agree that USADA shall notify both athletes within 24 hours of any of the following occurrences: (1) the approval by USADA of a TUE application submitted by either athlete; and/or (2) the existence of and/or any modification to an existing approved TUE. Notification pursuant to this paragraph shall consist of and be limited to: (a) the date of the application; (b) the prohibited substance(s) or method(s) for which the TUE is sought; and (c) the manner of use for the prohibited substance(s) or method(s) for which the TUE is sought.”

How was Mayweather’s IV handled by USADA?

As previously noted, the weigh-in and IV administration occurred on May 1. The fight was on May 2. For 20 days after the IV was administered, USADA chose not to notify the Nevada State Athletic Commission about the procedure.

Finally, on May 21, USADA sent a letter to Francisco Aguilar and Bob Bennett (respectively, the chairman and executive director of the NSAC) with a copy to Top Rank (Pacquiao’s promoter) informing them that a retroactive therapeutic use exemption had been granted to Mayweather. The letter did not say when the request for the retroactive TUE was made by Mayweather or when it was granted by USADA.

Subsequent correspondence in response to requests by the NSAC and Top Rank for further information revealed that the TUE was not applied for until May 19 and was granted on May 20.

In other words, 18 days after the fight, USADA gave Mayweather a retroactive therapeutic use exemption for a procedure that is on the WADA “Prohibited Substances and Methods List.” And because of a loophole in its drug-testing contract, USADA wasn’t obligated to notify the Nevada State Athletic Commission or Pacquiao camp regarding Mayweather’s IV until after the retroactive TUE was granted.

Meanwhile, on May 2 (fight night), Pacquiao’s request to be injected with Toradol (a legal substance) to ease the pain caused by a torn rotator cuff was denied by the Nevada State Athletic Commission because the request was not made in a timely manner.

A conclusion that one might draw from these events is that it helps to have friends at USADA.

“It’s bizarre,” Don Catlin says with regard to the retroactive therapeutic use exemption that USADA granted to Mayweather. “It’s very troubling to me. USADA has yet to explain to my satisfaction why Mayweather needed an IV infusion. There might be a valid explanation, but I don’t know what it is.”

Victor Conte is equally perturbed.

“I don’t get it,” Conte says. “There are strict criteria for the granting of a TUE. You don’t hand them out like Halloween candy. And this sort of IV use is clearly against the rules. Also, from a medical point of view, if they’re administering what they said they did, it doesn’t make sense to me. There are more effective ways to rehydrate. If you drank ice-cold Celtic seawater, you’d have far greater benefits. It’s very suspicious to me. I can tell you that IV drugs clear an athlete’s system more quickly than drugs that are administered by subcutaneous injection. So why did USADA make this decision? Why did they grant something that’s prohibited? In my view, that’s something federal law enforcement officials should be asking Travis Tygart.”

Bob Bennett (who worked for the FBI before assuming his present position as executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission) has this to say: “The TUE for Mayweather’s IV - and the IV was administered at Floyd’s house, not in a medical facility, and wasn’t brought to our attention at the time - was totally unacceptable. I’ve made it clear to Travis Tygart that this should not happen again. We have the sole authority to grant any and all TUEs in the state of Nevada. USADA is a drug-testing agency. USADA should not be granting waivers and exemptions. Not in this state. We are less than pleased that USADA acted the way it did.”

If Bennett looks at what transpired before he became executive director of the NSAC, he might have further reason to question USADA’s performance.

The use of carbon isotope ratio (CIR) testing as a means of identifying the presence of exogenous (synthetic) testosterone in an athlete’s body was developed in part under the direction of Don Catlin. It has been used in conjunction with Olympic testing since the 1998 Winter Games in Nagano.

As noted earlier, USADA often declines to administer CIR testing to boxers on grounds that it is unnecessary and too expensive. The cost is roughly $400 per test, although VADA CEO Dr. Margaret Goodman notes, “If you do a lot of them, you can negotiate price.”

If VADA (which charges far less than USADA for drug testing) can afford CIR testing on every urine sample that it collects from a boxer, then USADA can afford it too.

“If you’re serious about drug testing,” says Victor Conte, “you do CIR testing.”

But CIR testing has been not been fully utilized for Floyd Mayweather’s fights. Instead, USADA has chosen to rely primarily on a testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio test to determine if exogenous testosterone is in an athlete’s system.

Testosterone and epitestosterone are naturally occurring hormones. Testosterone is performance enhancing. Epitestosterone is not.

A normal testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio is slightly more than 1-to-1. Conte says that one recent study of the general population “placed the average T-E ratio for whites at 1.2-to-1 and for blacks at 1.3-to-1.”

Under WADA standards, a testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio of up to 4-to-1 is acceptable. That allows for any reasonable variation in an athlete’s natural testosterone level (which, for an elite athlete, might be particularly high). If the ratio is above 4-to-1, an athlete is presumed to be doping.

Some athletes who use exogenous testosterone game the system by administering exogenous epitestosterone to drive their testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio down beneath the permitted ceiling. This can be done by injection or by the application of epitestosterone as a cream. In the absence of a CIR test, this masks the use of synthetic testosterone.

But there’s a catch. If an athlete tries to manipulate his or her testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio, it is difficult to balance the outcome. If an athlete uses too much epitestosterone - and the precise amount is difficult to calibrate - the result can be an abnormally low T-E ratio.

“In and of itself,” Conte explains, “an abnormally low T-E ratio is not proof of doping. The ratio can vary for the same athlete from test to test. But an abnormally low T-E ratio is a red flag. And if you’re serious about the testing, the next thing you do [after a low T-E ratio test result] is administer a CIR test on the same sample.”

Earlier this year, in response to a request for documents, the Nevada State Athletic Commission produced two lab reports listing the testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio on tests that it (not USADA) had overseen on Floyd Mayweather. In one instance, blood and urine samples were taken from Mayweather on Aug. 18, 2011 (prior to his Sept. 17 fight against Victor Ortiz). In the other instance, blood and urine samples were taken from Mayweather on April 3, 2013 (prior to his May 4 fight against Robert Guerrero).

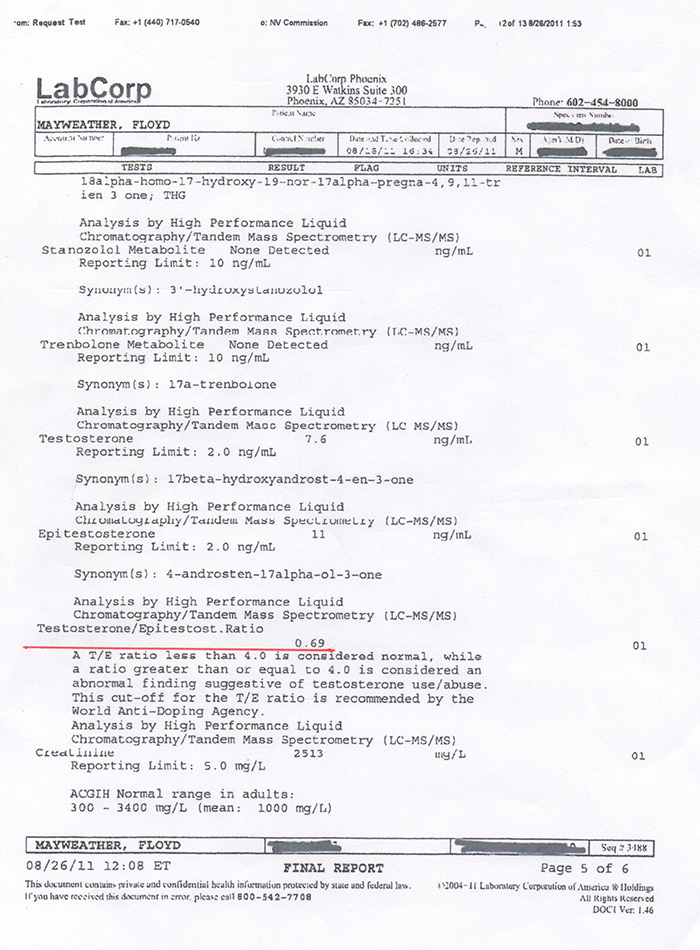

Mayweather’s testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio for the April 3, 2013, sample was 0.80. His testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio for the Aug. 18, 2011, sample was 0.69.

“That’s a warning flag,” says Don Catlin. “If you’re serious about the testing, it tells you to do the CIR test.”

The Nevada State Athletic Commission wasn’t as knowledgeable with regard to PED testing several years ago as it is now. Commission personnel might not have understood the possible implications of the 0.69 and 0.80 numbers. But USADA officials were knowledgeable.

Did USADA perform CIR testing on Mayweather’s urine samples during that time period? What were the results? And if there was no CIR testing, what testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio did USADA’s tests show? At present, the answers to these questions are not publicly known.

Note to investigators: CIR tests can be performed retroactively on frozen samples.

All of this leads to another issue. As noted by NSAC executive director Bob Bennett, “As of now, USADA does not give us the full test results. They give us the contracts for drug testing and summaries that tell us whether a fighter has tested positive or negative. It is incumbent on them to notify us if a fighter tests positive. But no, they don’t give us the full test results.”

Laz Benitez reports a similar lack of transparency in New York. On Aug. 10, Benitez advised this writer that the New York State Athletic Commission had received information from USADA regarding test results for four fights where the drug testing was conducted by USADA. But Benitez added, “The results received were summaries.”

Why is that significant? Because full test results can raise a red flag that’s not apparent on the face of a summary. Once again, a look at the relationship between USADA and Floyd Mayweather is instructive.

On Dec. 30, 2009, Manny Pacquiao sued Mayweather for defamation. Pacquiao’s complaint, filed in the United States District Court for Nevada, alleged that Mayweather and several other defendants had falsely accused him of using, and continuing to use, illegal performance enhancing drugs. The court case moved slowly, as litigation often does. Then things changed dramatically.

As reported by this writer on MaxBoxing in Dec. 2012, information filtered through the drug-testing community on May 20, 2012 to the effect that Mayweather had tested positive on three occasions for an illegal performance-enhancing drug. More specifically, it was rumored that Mayweather’s “A” sample had tested positive three times and, after each positive test, USADA had given Floyd an inadvertent use waiver. These waivers, if they were in fact given, would have negated the need to test Floyd’s “B” samples. And because the “B” samples were never tested, a loophole in Mayweather’s USADA contract would have allowed testing to continue without the positive “A” sample results being reported to Mayweather’s opponent or the Nevada State Athletic Commission.

Pacquiao’s attorneys became aware of the rumor in late-May. On June 4, 2012, they served document demands and subpoenas on Mayweather, Mayweather Promotions, Golden Boy (Mayweather’s co-promoter), and USADA demanding the production of all documents relating to PED testing of Mayweather in conjunction with his fights against Shane Mosley, Victor Ortiz, and Miguel Cotto. These were the three fights that Mayweather had been tested for by USADA up until that time.

The documents were not produced. After pleading guilty to charges of domestic violence and harassment, Mayweather spent nine weeks in the Clark County Detention Center. He was released from jail on Aug. 2. Then settlement talks heated up.

A stipulation of settlement ending the defamation case was filed with the court on Sept. 25, 2012. The parties agreed to a confidentiality clause that kept the terms of settlement secret. However, prior to the agreement being signed, two sources with detailed knowledge of the proceedings told this writer that Mayweather’s initial monetary settlement offer was “substantially more” than Pacquiao’s attorneys had expected it would be. An agreement in principle was reached soon afterward. The settlement meant that the demand for documents relating to USADA’s testing of Mayweather became moot.

If Mayweather’s “A” sample tested positive for a performance-enhancing drug on one or more occasions and he was given a waiver by USADA that concealed this fact from the Nevada State Athletic Commission, his opponent, and the public, it could contribute to a scandal that undermines the already-shaky public confidence in boxing. At present, the relevant information is not a matter of public record.

USADA CEO Travis Tygart (through senior communications manager Annie Skinner) declined to state how many times the “A” sample of a professional boxer tested by USADA has come back positive for a prohibited substance.

What is clear though, is that USADA is not catching the PED users in boxing. Tygart says that’s because his organization’s educational programs and the knowledge that USADA will catch cheaters deters wrongdoing. But the changing physiques and performance levels of some of the elite fighters tested by USADA suggest otherwise.

A simple comparison will suffice. As of Aug. 1, 2015, VADA had conducted drug testing for 18 professional fights. Three of the fighters tested by VADA (Andre Berto, former IBF-WBA 140-pound champion Lamont Peterson, and former 135-pound WBA titleholder Brandon Rios) tested positive for a banned substance.

Contrast that with USADA. Annie Skinner says that Mayweather-Berto will be the 46th fight for which USADA has conducted drug testing. In an Aug. 14, email she acknowledges, “At this time, the only professional boxer under USADA’s program who has been found to have committed an anti-doping rule violation is Erik Morales.”

One can speculate that, had Halestorm Sports not broken the Morales story, USADA might not have “found” that Morales committed an anti-doping violation either.

“USADA’s boxing testing program is propaganda; that’s all,” says Victor Conte. “It has one set of rules for some fighters and a different set of rules for others. That’s not the way real drug testing works. Travis Tygart wants people to think that anyone who questions USADA is against clean sport. But that’s nonsense.”

After Lance Armstrong’s defoliation for illegal PED use, Tygart was interviewed by Scott Pelley on 60 Minutes. Armstrong, Tygart declared, was “cowardly” and had “defrauded millions of people.”

Pelley then asked, “If Lance Armstrong had prevailed in this case and you had failed, what would the effect on sport have been?”

“It would have been huge,” Tygart answered, “because athletes would have known that some are too big to fail.”

“And the message that sends is what?” Pelley pressed.

“Cheat your way to the top. And if you get too big and too popular and too powerful, if you do it that well, you’ll never be held accountable.”

USADA is the dominant force in American sports insofar as drug testing is concerned. But it is not too big and powerful to be held accountable.

The essence of boxing is such that all participants are at risk. The increasing use of performance enhancing drugs makes these risks unacceptable.

Fighters are entitled to an initial presumption of innocence when questions arise regarding the use of performance enhancing drugs. Based on their performance, Muhammad Ali (blessed with preternatural speed and stamina) and Rocky Marciano (who absorbed incredible punishment and seemed to grow stronger as a fight wore on) might have been suspected of illegal drug use had PEDs been available to them.

But fighters who are clean are also entitled to know that they’re not facing an opponent who has augmented his firepower through the use of performance enhancing drugs. And any state athletic commission that fails to limit the use of PEDs within its jurisdiction is unfit to regulate boxing.

Richard Pound was one of the founders and the first president of the World Anti-Doping Agency. On May 13, 2013, a committee that Pound chaired submitted a report entitled “Lack of Effectiveness of Testing Programs” to WADA.

In part, that report states, “The primary reason for the apparent lack of success of the testing programs does not lie with the science involved. While there may well be some drugs or combinations of drugs and methods of which the anti-doping community is unaware, the science now available is both robust and reliable. The real problems are the human and political factors. There is no general appetite to undertake the effort and expense of a successful effort to deliver doping-free sport. This applies with varying degrees at the level of athletes, international sport organizations, national Olympic committees, national anti-doping organizations, and governments. It is reflected in low standards of compliance measurement, unwillingness to undertake critical analysis of the necessary requirements, unwillingness to follow-up on suspicions and information, unwillingness to share available information, and unwillingness to commit the necessary informed intelligence, effective actions, and other resources to the fight against doping in sport.”

A website and those who write for it are not the final arbiters of whether USADA has acted properly insofar as drug testing in boxing is concerned. Nor can they fully investigate USADA. But Congress and various law enforcement agencies can.

There’s an open issue as to whether USADA has become an instrument of accommodation. For an agency that tests United States Olympic athletes and receives $10 million a year from the federal government, that’s a significant issue.

Meanwhile, the presence of performance enhancing drugs in boxing cries out for action. To ensure a level playing field, a national solution with uniform national testing standards is essential. A year-round testing program is necessary. It should be a condition of being granted a boxing license in this country that any fighter is subject to blood and urine testing at any time. While logistics and cost would make mandatory testing on a broad scale impractical, unannounced spot testing could be implemented, particularly on elite fighters.

All contracts for drug testing should be filed upon execution with the Association of Boxing Commissions and the governing state athletic commission. Full tests results, not just summaries, should be disclosed immediately to the governing commission. A commission doctor should review all test results as they come in.

As the Pound Report states, “The objective is to improve the efficacy of testing procedures and other anti-doping activities, not merely to rely on having performed a certain number of tests.” Also, as recommended by the Pound Report, “CIR testing for artificial testosterone should be increased forthwith.”

Ten years ago, John Ruiz lost a 12-round decision to James Toney in a heavyweight championship fight at Madison Square Garden. Then Toney tested positive for nandrolone. The outcome of the fight was changed to no decision. Toney was suspended for 90 days, and Ruiz was reinstated as champion.

“The only sport in which steroids can kill someone other than the person using them is boxing,” Ruiz said afterward. “You’re stronger when you use steroids. You’re quicker and faster. If a baseball player uses steroids, he hits more home runs. So what? I’m not saying that it’s right, but you’re not putting anyone else at risk. When a fighter is juiced, it’s dangerous.”

Then Ruiz observed, “People go crazy about the effect that steroids have when a bat hits a ball. What about when a fist hits a head?”