In 1989, an eighteen-year-old South African named Elon Musk approached a girl at a party in Canada, where he was attending college, and said, “I think a lot about electric cars. Do you think about electric cars?” That anecdote, one of scores that make up Ashlee Vance’s chatty, eponymous biography of the forty-four-year-old entrepreneur, is telling. Long before Musk parlayed the $165 million he made for his part in developing the Internet banking giant PayPal into the more than $11 billion that underwrite Musk Industries today, he was thinking ahead, envisioning a world that merged science with science fiction, a real world that he, the hero of this story, would bring to fruition.

In the decades since, Musk has built the world’s leading electric car company, Tesla Motors, beating Detroit at its own game: in November 2012, the Tesla Model S, a seven-seat sedan that sold for as much as $100,000, was named Motor Trend magazine’s car of the year. At the same time, Musk founded, funded, and runs the aeronautics company SpaceX, and he conceived and is the board chairman of SolarCity, “the country’s premier solar services company.”

Though they are distinct businesses, run independently, the three are connected, in ways big and small. Tesla cars are sold with the guarantee of free fuel in the form of solar energy from charging stations powered by solar panels supplied by SolarCity. And the lithium-ion battery technology that allows a Tesla car to go from zero to sixty miles per hour in less than five seconds and travel three hundred miles on a single charge was instrumental in solving one of solar power’s biggest obstacles—its unreliability due to cloudy days, the dark of night, and latitude. This past spring, Tesla unveiled a stylish, compact, affordable home battery called Powerwall that stores the sun’s energy and kicks in when the solar panels are unproductive. “Our goal here is to fundamentally change the way the world uses energy,” Musk declared at the product launch. “The goal is complete transformation of the entire energy infrastructure of the world.” (Another synergy, reported by Bloomberg: the Powerwall battery will be available in colors “similar to the paint used for Tesla’s Model S sedan.”)

An even more significant connection is this: while Musk is working to move people away from fossil fuels, betting that the transition to electric vehicles and solar energy will contain the worst effects of global climate change, he is hedging that bet with one that is even more wishful and quixotic. In the event that those terrestrial solutions don’t pan out and civilization is imperiled, Musk is positioning SpaceX to establish a human colony on Mars. As its website explains:

SpaceX was founded under the belief that a future where humanity is out exploring the stars is fundamentally more exciting than one where we are not. Today SpaceX is actively developing the technologies to make this possible, with the ultimate goal of enabling human life on Mars.

“The key thing for me,” Musk told a reporter for The Guardian in 2013,

is to develop the technology to transport large numbers of people and cargo to Mars…. There’s no rush in the sense that humanity’s doom is imminent; I don’t think the end is nigh. But I do think we face some small risk of calamitous events. It’s sort of like why you buy car or life insurance. It’s not because you think you’ll die tomorrow, but because you might.

To be clear, Musk is not envisioning a colony of a few hundred settlers on the Red Planet, but one on the order of Hawthorne, California, the 80,000-plus industrial city outside of Los Angeles where SpaceX has its headquarters.

Until Elon Musk and his billion or so dollars came along around the turn of the century, space exploration in the United States had largely stalled. Musk recalls checking the NASA website for the space agency’s schedule for a Mars mission, not finding one, and assuming he was simply looking in the wrong place. When he realized he wasn’t, and that the government was unlikely to fund such a project, he decided to take it on himself. As he told Wired’s Chris Anderson a decade later, in 2012:

I started with a crazy idea to spur the national will. I called it the Mars Oasis missions. The idea was to send a small greenhouse to the surface of Mars, packed with dehydrated nutrient gel that could be hydrated on landing. You’d wind up with this great photograph of green plants and red background—the first life on Mars, as far as we know, and the farthest that life’s ever traveled. It would be a great money shot, plus you’d get a lot of engineering data about what it takes to maintain a little greenhouse and keep plants alive on Mars. If I could afford it, I figured it would be a worthy expenditure of money, with no expectation of financial return.

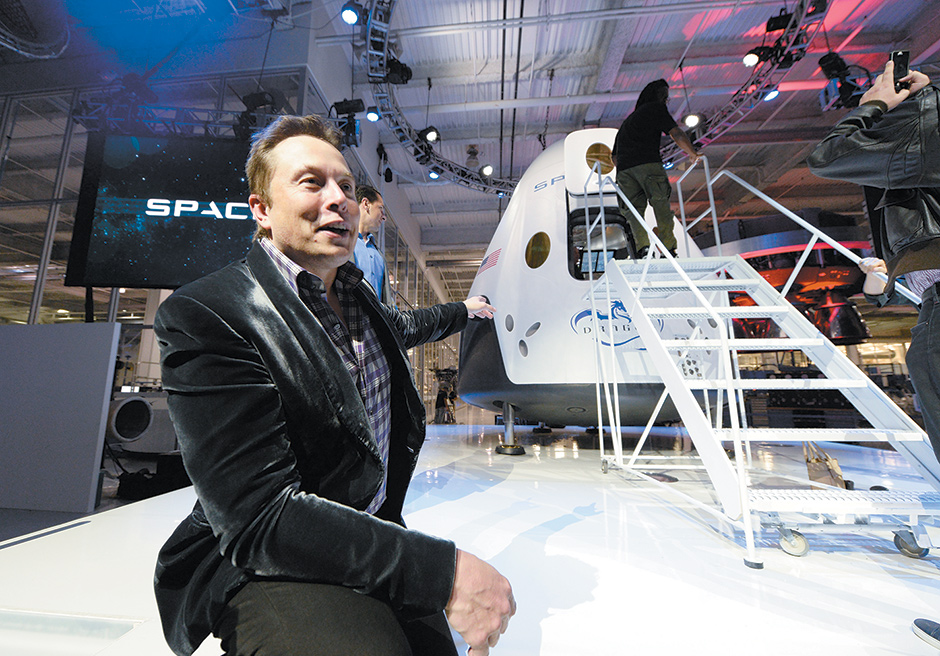

Musk, it should be noted, had no experience building rockets. All he knew about space exploration had been gleaned from books and training manuals. Vance describes in gleeful detail Musk’s improbable quest to build a NASA-worthy rocket essentially from scratch. “I am a billionaire. I am going to start a space program,” Vance reports him saying to the man he enlisted to go with him to Moscow to persuade the Russians to sell him an intercontinental ballistic rocket, which he planned to use as a launch vehicle. When that didn’t work out—Musk thought the Russians were trying to get him to part with too many millions of his billion-plus fortune—he crunched some numbers and determined that it made more sense to build the rocket himself. It would be low-cost, low-orbiting, and designed to ferry satellites into space on a regular schedule. The idea, he told the first employees of his new company, Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX), was to become the “Southwest Airlines of Space.”

Advertisement

As a private company, SpaceX could operate lean, absent the bloated bureaucracies and cost overruns of government contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin. It would embody the spirit of a Silicon Valley start-up—learn by doing and do it around the clock—and like those start-ups, it would take advantage of exponential increases in computing power. Software developers would tap into that power to design and build the company’s avionics, while the rocket’s components would be assembled, as much as possible, from equipment purchased off the shelf. But when suppliers couldn’t deliver a product fast enough, or when it didn’t meet Musk’s standards, he would declare that SpaceX could make the same part quicker, better, and cheaper. And then, invariably, because of Musk’s relentless and successful pursuit of the best young engineers and coders and the unremitting demands he placed upon them, it would be made. Before long, in-house development became an integral part of the SpaceX mission, vital to keeping costs low enough to make a private enterprise space program workable.

What was not workable was the schedule Musk set when he announced the creation of the company in 2002—a first rocket launch fifteen months later, and a Mars expedition seven years after that. It took more than four years for SpaceX to send its first rocket aloft, in March 2006; it fell to earth and crashed in less than half a minute. To get even that far, the SpaceX team had had to design, manufacture, and assemble the rocket’s engine, its fuselage, and the avionics software that was driving the whole operation. They were also tasked with building a launch pad and control tower on Kwajalein, a remote atoll in the Marshall Islands.

After the failure of the first rocket, it took a full year to analyze what went wrong, correct for it, construct a new spacecraft, and send it skyward. Though this one flew longer than the first, it, too, fell back to earth. The company was burning through Musk’s money; its margin for error was narrowing while Musk’s reputation as yet another rich guy with a vanity space program was growing. Finally, in 2008, six years after Musk declared his galactic intentions, and four and a half years after he said it would happen, the SpaceX Falcon 1 became the first privately constructed rocket to reach orbit. As Vance tells it, the human costs were at least as high as whatever number of dollars had come from Musk’s pocket (one estimate put it at $100 million):

Some of these people had spent years on the island going through one of the more surreal engineering exercises in human history. They had been separated from their families, assaulted by the heat, and exiled on their tiny launchpad outpost—sometimes without much food—for days on end as they waited for the launch windows to open and dealt with the aborts that followed. So much of that pain and suffering and fear would be forgotten if this launch went successfully.

Maybe. Possibly. Probably not. The portrait of Elon Musk that emerges from these pages is of a man of visionary intellect, fierce ambition, and fantastic wealth, who is emotionally bankrupt. “Many of us worked tirelessly for him for years and were tossed to the curb like a piece of litter,” one former employee told Ashlee Vance. “What was clear is that people who worked for him were like ammunition: used for a specific purpose until exhausted and discarded.”

Vance tells the story of Mary Beth Brown, Musk’s longtime personal assistant and one of the first SpaceX hires—the woman who scheduled his meetings, picked out his clothes, did public relations, ran interference, and made executive decisions, logging twenty-hour days when necessary—who lost her job when she asked for a raise:

Advertisement

Musk [told her, when she asked for more money] that Brown should take a couple of weeks off, and he would take on her duties and gauge how hard they were. When Brown returned, Musk let her know he didn’t need her anymore….

So it went for many of Musk’s most devoted employees. Loyalty was expected but not honored. Fear of getting publicly dressed down by Musk—or worse—was rampant. “Marketing people who made grammatical mistakes in e-mails were let go,” Vance reports, “as were other people who hadn’t done anything ‘awesome’ in recent memory.” And then there was the employee who “missed an event to witness the birth of his child. Musk fired off an e-mail saying, ‘That is no excuse. I am extremely disappointed. You need to figure out where your priorities are. We’re changing the world and changing history, and you either commit or you don’t.’”

Musk’s severe rationality and emotional detachment, as well as his preternatural ability to master complex subjects quickly, have led to an ongoing joke among denizens of certain Internet forums that he must be an alien, beamed down from space. (No wonder he’s so keen to colonize Mars!) In fact, the man has all the attributes of a classic narcissist—the grandiosity, the quest to be famous, the lack of empathy, the belief that he is smarter than everyone else, and the messianic plan to save civilization. Steve Jobs comes to mind, though Jobs’s ambitions were pedestrian compared to Musk’s. Still, by now the fabulously wealthy, fabulously self- justifying Silicon Valley CEO has become a familiar figure. It’s as if inhumane behavior were a necessary and expected part of the tech narrative. Without it, the story loses its frisson. Would a biography like this be half as thrilling if its protagonist were not a colossal jerk?

This is not to deny that the achievements of Musk Industries have been considerable. Tesla Motors produces cars that have shown the viability of long-distance electric vehicles. Combine that with SolarCity’s ever-expanding solarization of the energy grid and suddenly a post-carbon future that does not require a diminution of our standard of living seems within reach. While being able to maintain a relatively upscale lifestyle in the absence of fossil fuels may sound frivolous, it performs the psychological trick that has so far eluded environmentalists, that of making a fossil-free world sound appealing and familiar and not reflexively scary.

Though so far Tesla cars are only available to the monied few, the cars, as proof of a concept, have had an impact beyond their numbers, not only because they have been so well received by both consumers and the automobile industry, but because they have inspired other car manufacturers to move toward electric power. Twelve electric vehicles besides the Tesla Model S were brought to market in 2014 and fourteen were released in 2015. One of them was conceived and designed in Croatia. If any of these companies can make an affordable, long-distance electric car, then electric vehicles could, in the not too distant future, become the new normal, relegating the internal combustion engine, with its pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, to the junk heap of history. Musk himself promises such a car within two years.

Similarly, Musk’s Powerwall is another proof of concept. It may not change the way electricity is generated, at least not in developed countries with existing infrastructure, but it does make going off the grid more feasible and affordable. In developing nations, it has the potential to offer electrification without the monetary and health costs of constructing coal-fired power plants or large-scale dam projects. Right now, the large factory Musk is building in Nevada to produce these batteries cannot keep up with demand. This is a good sign, and not just for Musk. Given the opportunity to switch to renewable energy, consumers are taking it.

This is how markets are supposed to work. Last year Musk did an about-face and made all of Tesla’s automobile patents open-source, available to anyone to use “in good faith,” in an effort to spur more electric vehicle development. But even if he is not directly inviting competitors, other manufacturers are following Musk’s lead. Shortly after Musk launched the Powerwall, Daimler, the parent company of Mercedes-Benz, announced its own wall-mounted home battery pack. This was no coincidence. In 2009, Daimler bought a 10 percent stake in Tesla, and Tesla, which already had provided battery packs for a fleet of Mercedes A Class cars, agreed to make them for Daimler’s Smart cars, too.

SpaceX, which is the first private company to deliver supplies to the International Space Station, and which in 2017 plans to bring astronauts there, has inspired aerospace giant Airbus to develop its own reusable launch vehicle similar to a SpaceX system now being tested that would make spacecrafts more like airplanes. (SpaceX was able to land one of its Falcon rockets on water in 2014 and is getting close to being able to guide one down to the launch pad. However, a major setback occurred on June 28 when a Falcon 9 rocket bound for the International Space Station exploded and disintegrated less than three minutes after launch, taking 4,300 pounds of cargo with it. It was the first Falcon 9 failure in nineteen flights.)

And it’s not only industry responding to Musk’s initiatives. Two years after the creation of SpaceX, President George W. Bush announced an ambitious plan for manned space exploration called the Vision for Space Exploration. Three years later, NASA chief Michael Griffin suggested that the space agency could have a Mars mission off the ground in thirty years. (Just a few weeks ago, six NASA scientists emerged from an eight-month stint in a thirty-six-foot isolation dome on the side of Mauna Loa meant to mimic conditions on Mars.) Musk, ever the competitor, says he will get people to Mars by 2026. The race is on.

But how are those Mars colonizers going to communicate with friends and family back on earth? Musk is working on that. He has applied to the Federal Communications Commission for permission to test a satellite-beamed Internet service that, he says, “would be like rebuilding the Internet in space.” The system would consist of four thousand small, low-orbiting satellites that would ring the earth, handing off services as they traveled through space. Though satellite Internet has been tried before, Musk thinks that his system, relying as it does on SpaceX’s own rockets and relatively inexpensive and small satellites, might actually work. Google and Fidelity apparently think so too. They recently invested $1 billion in SpaceX, in part, according to The Washington Post, to support Musk’s satellite Internet project.

While SpaceX’s four thousand circling satellites have the potential to create a whole new meaning for the World Wide Web, since they will beam down the Internet to every corner of the earth, the system holds additional interest for Musk. “Mars is going to need a global communications system, too,” he apparently told a group of engineers he was hoping to recruit at an event last January in Redmond, Washington. “A lot of what we do developing Earth-based communications can be leveraged for Mars as well, as crazy as that may sound.”

And then—talk about crazy—there is the hyperloop, a super-fast transportation system (San Francisco to Los Angeles in thirty minutes at more than seven hundred miles per hour) in which passengers travel in pods through something like pneumatic tubes that Musk has described as “a cross between a Concorde, a railgun and an air hockey table.” He started imagining this “fifth mode of transportation,” he said, in response to a plan by the California Department of Transportation to build a bullet train that, by his estimation, would be one of the most expensive and slowest fast trains in the world. Musk’s idea was to

mount an electric compressor fan on the nose of the pod that actively transfers high pressure air from the front to the rear of the vessel. This is like having a pump in the head of the syringe actively relieving pressure.

Because, he said, he was too busy making rockets and electric cars, he released his technical paper, “Hyperloop Alpha,” to the public, hoping that others would pursue it.

They have. There are at least two groups with similar names, Hyperloop Technologies and Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, the first with a roster of Silicon Valley venture capital all-stars, the other raising money by crowdsourcing, who have set up shop—both in Los Angeles—and are working on the hyperloop in earnest. In recent months, Musk has jumped back on board, pledging to build a test track adjacent to SpaceX, and announcing a contest, open to students and independent engineering teams, to design and construct prototypes of the system’s passenger pods. They will be put to the test next summer. So far over seven hundred contestants have entered.

Musk’s critics—and he has many—are quick to point out that he is merely piggy-backing on existing technologies, not inventing them. There were electric cars before there was Tesla, rockets before there was SpaceX, solar panels before there was SolarCity, and even pneumatic tube travel has a long, if spotty, history. Yet as true as this is, it misses the point of what Elon Musk is doing. By now it is a cliché to put the words “Silicon Valley” and “disruptive innovation” in the same sentence, but disruption is precisely the point of every one of Musk’s ventures. He has made disruption itself his business plan and it is working. It required a lot of hubris to take on the aerospace industry and the automobile industry and the utilities, but he did, and he is, with precipitous consequences. Will they be precipitous enough to catapult the man to Mars, ten years hence?