“When the sixties finally ended in Berkeley, sometime around 1994, the only thing left standing from that bygone era was the Cheese Board.”

— Alice Kahn, as quoted in The Cheese Board Collective Works

***

Even on a Wednesday afternoon, the Cheese Board pizza shop does brisk business.

The line stretches around the block. But if you check the restaurant’s reviews, or just get in line, you’ll discover that this line moves very, very fast. A jazz trio noodling in the dining area entertains the waiting patrons. At the register, a smiling young Mexican man takes your order and then asks you to stand to the side. Seconds later, a woman with intricately-tattooed arms hands you your half-pie.

You sit down and realize she’s given you a few extra slivers to munch on while waiting for your friend. You nibble one and decide you should have ordered a whole pie. (“I live in New York and already miss this pizza,” one online reviewer wrote.) Maybe if your friend is late enough, you will. But who would have thought roasted sweet potato, pasilla pepper, lemon zest, and hard goat cheese would make such a winning topping combination? You were skeptical when you heard it was the only option today.

It shouldn’t surprise you that the pizza is so good or that the line moves so fast or that the service is so friendly. The woman who handed you the pizza is one of the owners — she left a corporate job to run the place.

The young man at the register is an owner, too, and the pizza you’re eating is his recipe. He’s watching you out of the corner of his eye; if customers like the recipe enough, he and the other owners will discuss adding it to the regular menu. A third owner sits a few tables down. She made the dough for the crust this morning. Now she’s here off-shift, grabbing lunch and checking out the band she booked.

The woman asking if she can bus your now-empty pizza tray is also an owner, as is the guy refilling the hot sauce and the man running pizzas back and forth between the oven and the counter. The young woman who will sweep up your crumbs when the store closes at 3pm, shortly before it opens again for equally bustling dinner hours at 4:30pm, is an owner in-training.

The Cheese Board currently has dozens of owners. And within the San Francisco Bay Area, over one hundred of the hippest, hardest-working foodies around own and operate another six affiliated bakery/pizzerias.

Not Your Average Hippie Entrepreneurs

The cheese branch of the Cheese Board Collective (SloopRiggedSkiff)

Elizabeth and Sahag Avedisian could have been moguls if they wanted.

In 1967, the married couple opened the Cheese Board as a simple cheese shop on a “quiet corner of a small college town” that didn’t yet serve pizza. At first it appeared ill-advised: the Avedisians didn’t have any experience in retail, and they didn’t know very much about cheese.

But this was Berkeley’s bourgeoning “Gourmet Ghetto.” There was a popular grocery co-operative a few blocks away from the shop in one direction. Two blocks in the other direction, the world’s first Peet’s Coffee & Tea — now a national chain and publicly-traded company — was just getting started. Most importantly, there was a growing market for the “authentic and imported” cheeses the Avedisians quickly learned about and stocked.

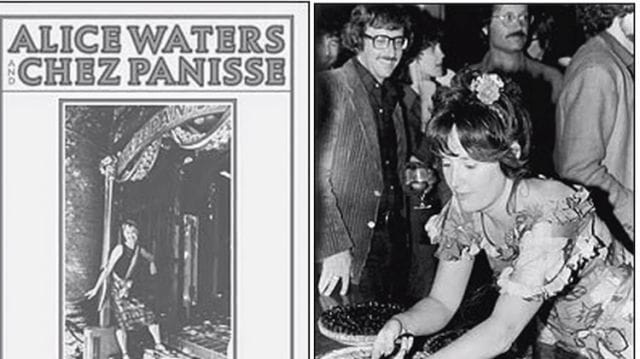

In 1971, Alice Waters opened Chez Panisse in the same neighborhood. Today, many consider Chez Panisse the best restaurant in the world, and Waters is a full-on celebrity. Not only has she written best-selling books, she’s had best-selling books written about her. In 1992, she became the first woman named “Best Chef in America,” and she has been hailed as the “mother of American cooking.”

But in 1971, Waters was a fresh college grad who wanted to run a “little restaurant” and make a “good living.” She has said that when she opened Chez Panisse, she “made sure the Cheese Board would be nearby, because I knew I would be among friends.”

Alice Waters in the 1970s (DarkBlueImaginarium)

While Waters remained an artisan through her success, plenty of other hippie entrepreneurs grew companies like Peet’s, Burt’s Bees, and Ben & Jerry’s into multi-million dollar corporations. But the Avedisians didn’t want to run a multi-million dollar corporation. They didn’t want to “run” anything, at least not by themselves or as executives.

Utopian ideas held sway in the 1960s and the 1970s, and many popular visions of utopia involved non-hierarchical power structures. In other words, people dreamed of a world without bosses. The grocery store up the street was a consumers’ co-operative. Sahag Avedisian had lived on a kibbutz in Israel, and the Avedisians had mostly staffed the Cheese Board with their friends and patrons. As Alice Waters’ statement implied, by 1971, the Cheese Board was more than just a cheese shop. It was a cornerstone of the community.

So, in 1971, the Avedisians sold their cheese shop to its six employees at cost. “It felt to me that Sahag and Elizabeth were just giving the place away,” Tessa Morrone, a former member of the co-operative said. “I had never heard of anything like that.”

Pat Darrow, the Cheese Board’s first employee, recalled, “We were marching for peace, but we had not heard anyone say the owner should not make money off the workers. That was amazing to me!”

That same year, Waters opened her restaurant, and the Cheese Board helped inaugurate it. Waters described the moment in the foreword she wrote for The Cheese Board Collective Works cookbook:

“I know I will never forget the astonishing night when the merry collectivists, having stripped themselves naked, burst through the front door in the midst of dinner service and streaked through the restaurant, the very embodiment of ecstatic, anarchic nature, if not anarcho-syndicalism.”

By then, the Cheese Boarders were “collectivists,” and the Cheese Board was a “collective.” The pay structure was completely egalitarian: Everybody earned the same wage, no matter how senior they were. They made decisions about the shop’s operations through some form of consensus, even if it made for some very long meetings. This operating model and pay structure remain the same today.

Cheese Shop + Bread + Toppings = Pizza

Television footage of the Cheese Board in the 1970s (JJNoire)

Through its early years, the Cheese Board sold only cheese. Authentic, imported cheese.

Then, in the mid-1970s, a few members of the collective started making bread to occasionally serve with cheese samples. Baking bread requires a completely separate skill set from buying and selling cheese, so for a while the quality of the loaves hovered between “interesting” and “terrible.” But flour is cheap, and as the bread was free, customers couldn’t complain. And the bakers didn’t have to worry about the management yelling at them, because they were the management.

They kept baking, and they got better. Eventually they made loaves good enough to sell, and just like that, the Cheese Board was a bakery. A popular bakery. An early Cheese Board member has recalled, “Back when we first started making baguettes, almost nobody [in Berkeley] knew what a baguette was. Ten years later, you would see as many people walking around with a baguette under their arm as you would in Paris.”

Once you have cheese and bread dough in the same kitchen, it’s only a matter of time before somebody makes pizza. It happened in 1985, when business was slow and pocket change was scarce. As The Cheese Board Collective Works tells it, the first Cheese Board pizzas were made as an economical staff lunch:

“Someone grabbed cheese from the case, someone else would run next door to the Produce Center for vegetables. A half hour later, pizza was served. Customers noticed and wanted a piece, too. Before we knew it, we were selling slices for lunch.”

Today’s recipes echo these beginnings: fresh vegetable toppings and high-quality, exotic cheeses on a sourdough crust. Sauce is usually only included as a garnish, to taste. The bakery only offers one combination of toppings each day, though the pizza-of-the-day varies widely within a given week.

Broccoli, red onion, fontina, mozzarella, cheese, garlic oil, gremolata. (Sherrymain)

Pizza sales pulled the Cheese Board out of a recession-era slump and turned business around in a big way. Pizza was such a financial boon that the Cheese Board opened a dedicated pizzeria in 1990. This pizzeria now has a space of its own, adjacent to the cheese shop and bakery. The members opted to take a temporary pay cut so they could have the funds to acquire and remodel the space when it became available. Even though the line for pizza moves very fast, it often curls round the block.

Business is booming, but as explained in The Collective Works, the Cheese Board owners aren’t interested in expanding further:

“We want to promote worker cooperatives, but not at the risk of changing our own scale or culture. Some of our lack of ambition can be attributed to a philosophical distaste for society’s dependence on and glorification of growth and expansion, and some can be because of our natural inclination to take it easy, and keep things on a smaller scale.”

Still, it’s hard to keep something so successful from spreading — in one way or another.

A Cooperative of Cooperatives

Arizmendi Bakery (Granite Porch Productions)

In 1995, one of the Cheese Board’s owners wanted to open his own bakery pizzeria that followed the same, co-operative model. Along with a lawyer and a professor, he approached the Cheese Board asking for a loan and the advisory support to start a new bakery and pizzeria. The Cheese Board owners agreed.

“It’s not really in a cooperative’s interest to expand,” says Maddy Van Engle, who helps run a network of cooperative bakeries that now includes the Cheese Board and this bakery.

There are no high-pay, top-level executives at the Cheese Board, pushing for major expansion. Everybody is both a top-level executive and a bottom-level laborer. A coop may aim to maximize profits, but its main motive is for its owners to sustainably earn a good living, on their terms. Sometimes, expansion is a threat to that goal. Consensus meetings of the 50 current Cheese Board owners are already a challenge — 50 more would likely require restructuring the organization.

But even though the Cheese Board owners didn’t want to grow larger, they did want more worker co-ops to exist. “This was a way for them to help create new jobs and spread their business model,” Van Engle explains, “without making their own operation too large to function.”

They established the new bakery pizzeria (opting to stay out of the cheese retail business) in the adjacent city of Oakland in 1997. They named it “Arizmendi,” after Jose Maria Arizmendiarrieta Madariaga, a Spanish priest who founded the Mondragon network of cooperatives, which today have a collective workforce of over 100,000 and comprise the seventh-largest corporation in Spain.

Arizmendiarrieta with the Mondragon Cooperative (Universidad MONDRAGON UCO)

Arizmendi, the Oakland pizza bakery, was a success, and the owners paid back their loan to the Cheese Board. In 2000, a mere three years after the first loan, the two bakeries decided to do it again, and opened a second Arizmendi in nearby San Francisco.

Today, the Arizmendi Association of Cooperatives is made up of six cooperative bakery pizzerias distributed across the San Francisco Bay Area. Taking their inspiration from the Mondragon Corporation, the Arizmendi Association is essentially a cooperative of cooperatives. One function of the Association is to help develop new cooperatives — historically, more bakery pizzerias on the Cheese Board model. Member cooperatives also pool their resources to support one another.

“The bakeries are all separately owned and run, so they all run differently,” Van Engle explains. “Some of the older ones have a little bit less structure, the newer ones have the most structure — as the bakeries have been created, more and more lessons have been learned.” Each cooperative has its own staff (who own the bakery they work at), its own menus (some sell more than one kind of pizza, for example), and its own wages (mostly a function of how well the individual bakery is doing). Not every bakery discloses wage information, but at the time of writing, owners of the Arizmendi in San Francisco’s Mission district make around $20 an hour in wages (there’s also a tip jar).

When it comes to decisions like whether to start a new bakery or change policies that affect more than one member bakery, they are made by the Association’s “Development and Support Cooperative” board. Besides Van Engle and two more full-time members, the board of the Association consists of two bakers from each bakery (12 bakers total). The member bakeries pay dues to the Association to support “new jobs in the future, and to fund legal, financial and personnel support, whenever it’s needed.”

A band plays at the Cheese Board pizzeria (DarkBlueImaginarium)

Van Engle was once a baker, too. She started working for Arizmendi bakery in 2010 as a baker without any baking experience. “Before that, I taught cooking and gardening to kids,” Van Engle says. “All of the work that I’ve done had to do with food justice.” She became deeply involved in the organizational aspects of the bakery, so much so that she was elected by the existing board to work for the Association full-time.

In her four years with the network, Van Engle says she’s learned a lot — and not just about pizza. “Not having a boss is challenging, in a really interesting way,” she says. “Most jobs involve trying to appease your boss, and bosses are supposed to manage workers below them to prevent conflict. But in a co-op, in a way, you have 20 bosses telling you 20 different ways to do things. And all the conflict comes up to the surface.” When it does, members have to learn how to deal, or else the bakery can’t function.

Van Engle says conflicts like these are more easily solved when everyone has a common cause they care about — in a cooperative’s case, that cause is the continued success of the coop. It also helps that virtually everyone has a deep understanding of the business. “Everyone’s doing everything,” she says, referring to the fact that each baker/owner is trained for, and often rotates into, many different aspects of running the company. “Everyone’s washing dishes, everyone’s management, everyone’s front and back of the house. People feel a lot of ownership,” she says. “People really care.”

In our next post, we use data to identify the world’s best and worst airports. To be notified when we post it, join our email list.

***

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here.