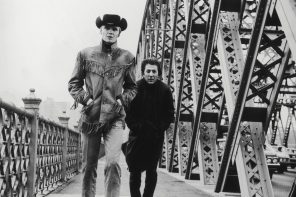

After Sam Peckinpah angered the studio with his Ballad of Cable Hogue, where he went 19 days over schedule and more importantly 3 million dollars over budget, he had a tough time finding a gig, so he decided to go to England to make Straw Dogs, a film based on Gordon M. Williams’ 1969 novel The Siege of Trencher’s Farm. “I’m like a good whore,” allegedly said Peckinpah at the time. “I go where I’m kicked.” Years later it turned out the filmloving community had much to be thankful for to Hollywood for forcing Peckinpah to move to Europe. Straw Dogs, as controversial and underappreciated as it was back in those days, is one of the great filmmaker’s career’s highlights and an extremely accomplished landmark of the seventies. The story of an American mathematician who moves to a small British village with his sexy young wife, only to be met with extreme hostility and brutal violence, is a thoughtful, full-blooded analysis of the dark side of human nature. Dustin Hoffman’s protagonist is full of repressed emotion, the release of which is triggered by the danger he finds his family to suddenly be in. The magnificently filmed festival of violence and blood-spilling was largely understood as fascist glorification, while the much debated rape scene caused shock and controversy mostly thanks to the ambiguous response from the victim, the mathematician’s wife played by the wonderful Susan George, who screams ‘no,’ but then seemingly enjoys the intercourse. Peckinpah made perfectly sure the audience understands her trauma and shock, but this was enough not only to create the label of notoriety, but also to ban it from the British audience’s view for a very long time.

The cuts made for American distribution, which were made to reduce the duration of the sequence, therefore tended paradoxically to compound the difficulty with the first rape, leaving the audience with the impression that Amy enjoyed the experience. The Board took the view in 1999 that the pre-cut version eroticised the rape and therefore raised concerns with the Video Recordings Act about promoting harmful activity. The version considered in 2002 is substantially the original uncut version of the film, restoring much of the unambiguously unpleasant second rape. The ambiguity of the first rape is given context by the second rape, which now makes it quite clear that sexual assault is not something that Amy ultimately welcomes. —The British Board of Film Classification

But the brilliant screenplay that Peckinpah co-wrote with David Zelag Goodman makes it clear that the film’s intentions are not voyeuristic as much as scientific or philosophical—Straw Dogs perfectly demonstrates the inner demons present in all of us, waiting for the right time and the suitable circumstances to emerge to the surface in an overwhelming bloodbath. Straw Dogs is thrilling, with carefully built, chilling atmosphere, it’s exciting, well-acted and much deeper than one would suspect. It’s one of Sam Peckinpah’s greatest films, and in the 45 years that passed since its release, its blade hasn’t lost any of its sharpness.

Dear every screenwriter/filmmaker, read David Zelag Goodman & Sam Peckinpah’s screenplay for Straw Dogs [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

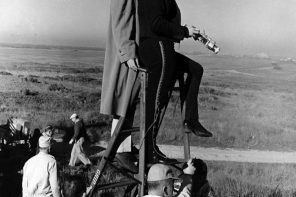

The director’s role was one accepted ambivalently by Sam Peckinpah, so much so that much of his work aimed to reconcile his positions as artist, employer and businessman, and entertainer. In his August, 1972, Playboy interview, he likened himself to a hired hand and a whore. It was just a job, directing, lucrative after some successes; on the other hand, writing was the most painstaking activity ever undertaken by a man. He seemed to denigrate his status and to knock his artistic capabilities; however, a look at The Wild Bunch, The Ballad of Cable Hogue, and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia reveals that whores, most of all, have a monopoly on humanity, nobility, and common sense among Sam’s characters. Furthermore, he who hired most of the film crew willfully opposed the demands and decisions of other bossmen: studio heads and the producers. Their interference left him with unequivocal feelings: “There are people all over the place, dozens of them, I’d like to kill, quite literally kill.” Metaphorically, he got his chance to kill them. —The Film Journal

Loading...

Loading...

SAM PECKINPAH’S 2 HOUR FILM SCHOOL

The track provides a two-hour film course on both film and filmmaker (unfortunately, the Criterion edition is out-of-print). Stephen Prince thoroughly analyzes each scene and performance while sprinkling his comments with nuggets of information about Peckinpah himself, and the result is an engrossing and exhaustive discussion about what makes the film so relevant four decades after its initial release. Prince is also the author of Savage Cinema: Sam Peckinpah and the rise of ultraviolent movies, among many other books and articles about film.

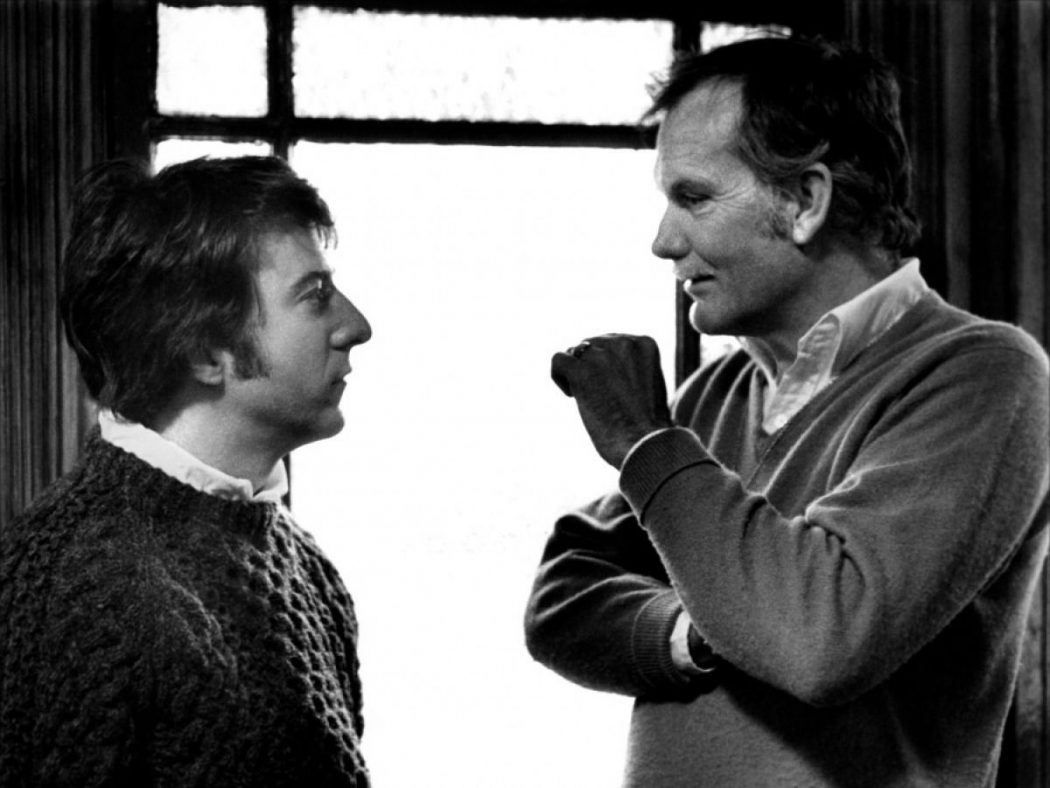

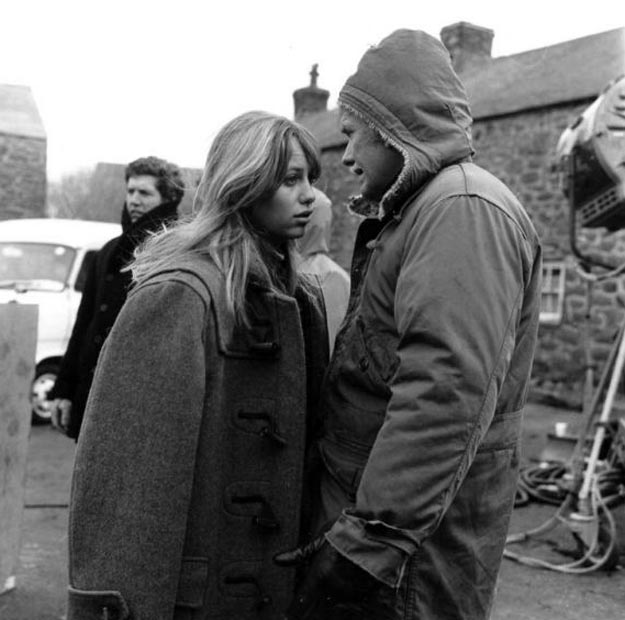

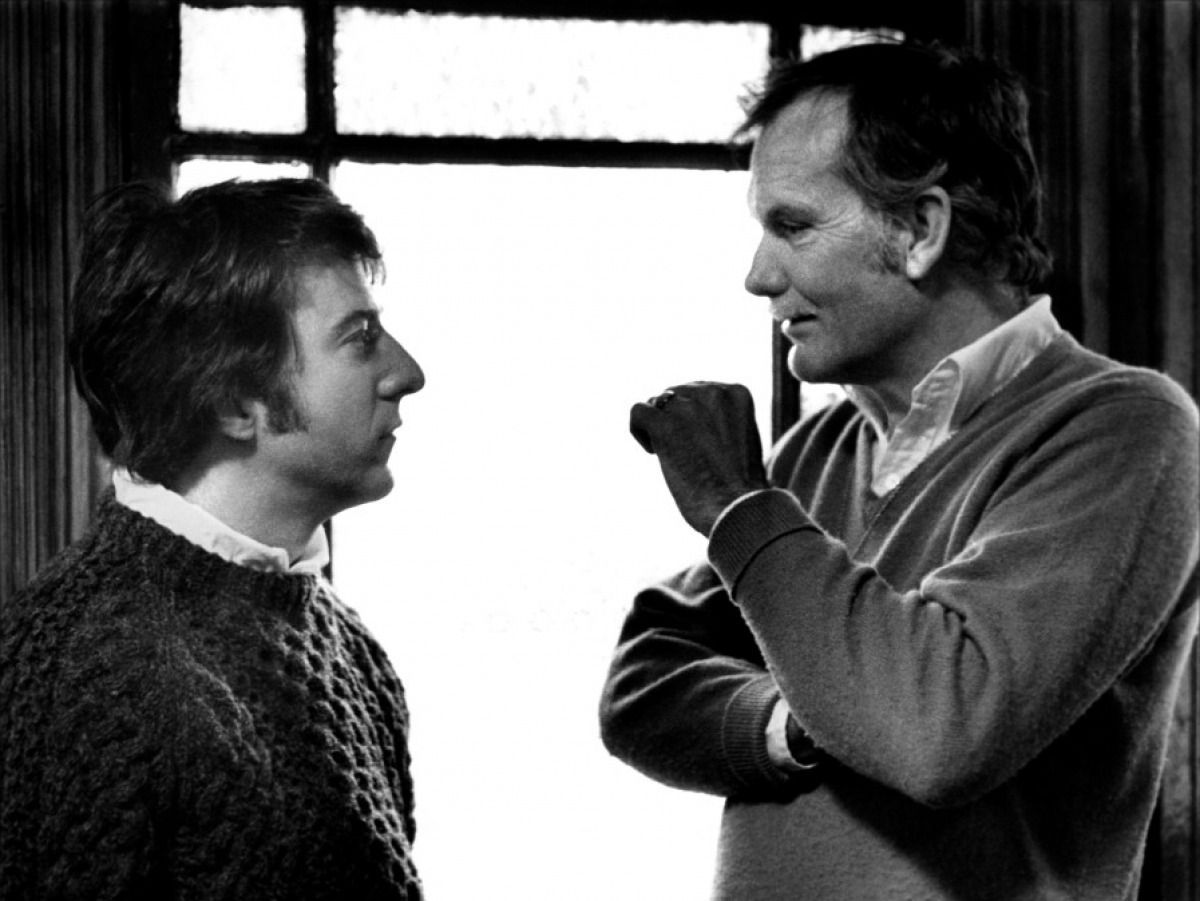

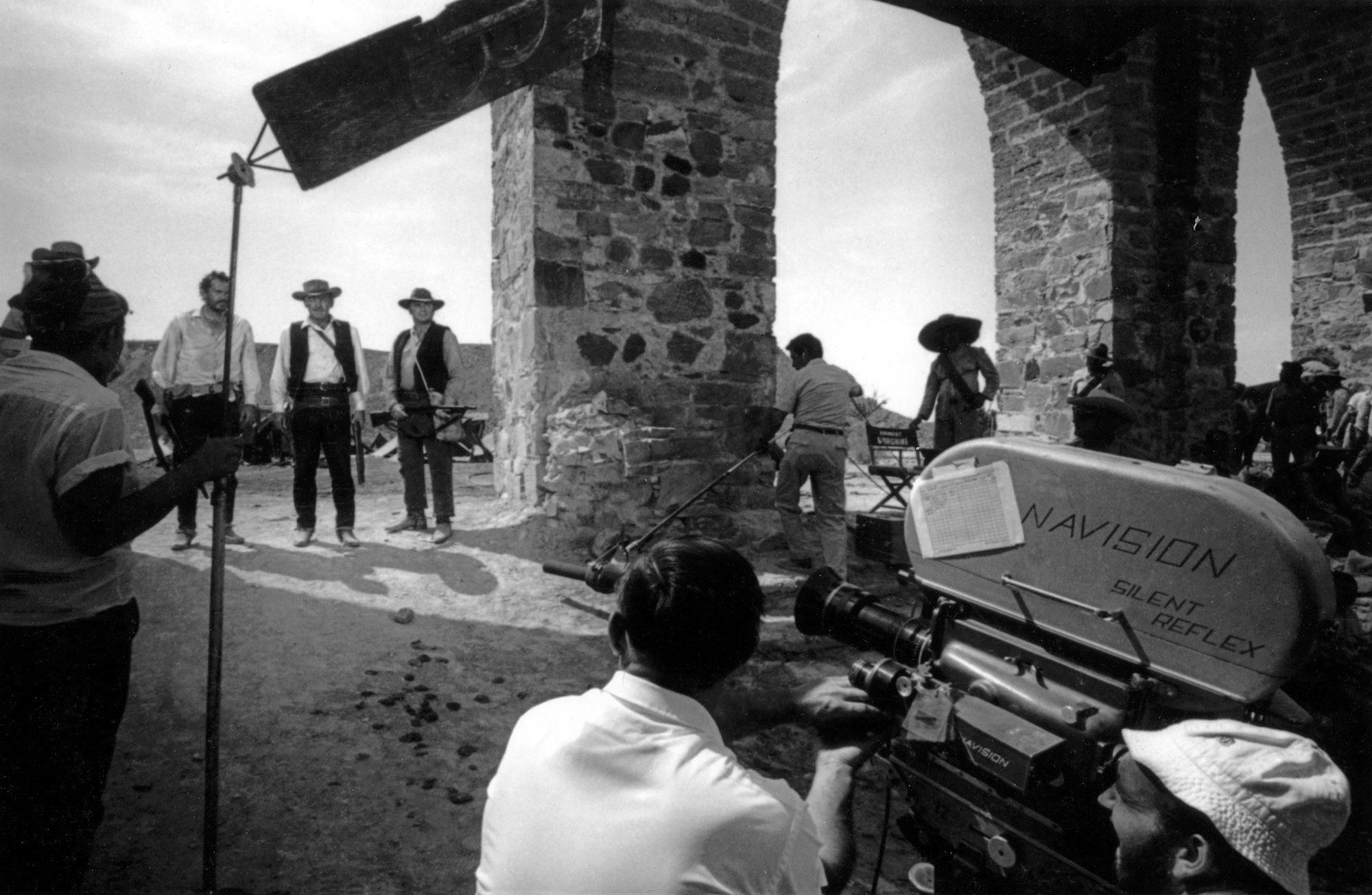

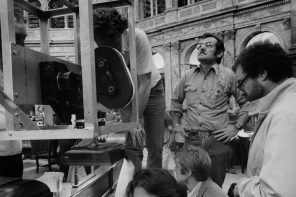

Black & white behind-the-scenes footage shot in 1971 on location of Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs. Interviews with Sam Peckinpah, Dustin Hoffman and Susan George.

A look behind the scenes of Peckinpah’s 1971 film, Passion & Poetry—Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs.

Man Trap: Straw Dogs: The Final Cut is Mark Kermode’s attempt to unravel the secrets of Sam Peckinpah’s most controversial film.

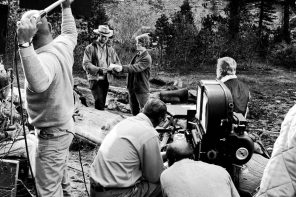

The making of Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs. Still photographer: John Jay. ABC Pictures, Talent Associates, Amerbroco. Straw Dogs director, Sam Peckinpah, goes over a production point with Dustin Hoffman as T.P. McKenna looks on. In the film, McKenna’s character wears his arm in a sling, though the sling was for real, his shoulder had been badly dislocated at a pre-shoot party organised by the director. Peckinpah looks very old Hollywood here with the cloth cap reversed and a cigarette hanging louchely from his mouth. His relaxation during set-up changes was knife-throwing. A version of this picture hung for many years in Luigi’s of Covent Garden which was London’s premiere restaurant for the theatre fraternity. Courtesy of tpmckgallery.blogspot.com

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in