Ocean plants 'can help freeze clouds'

- Published

Scientists say tiny ocean plants could play a significant role in the formation of ice in clouds.

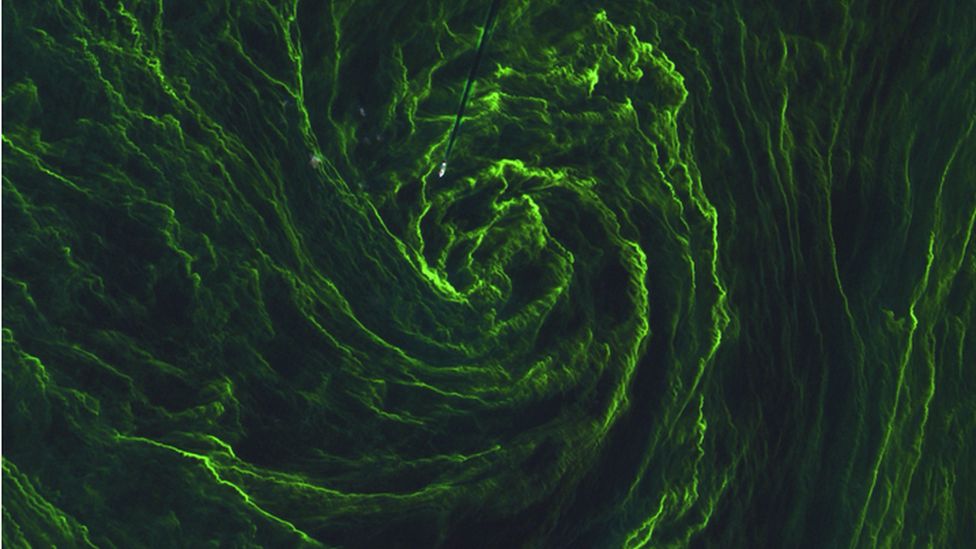

An international team has shown that the top few millimetres of the sea is rich in secretions from phytoplankton.

The group’s tests demonstrate that this microscopic material can nucleate ice crystals if lifted into the atmosphere by crashing waves and sea spray.

If this is a very prevalent process, it likely alters cloud properties, the researchers tell the journal Nature.

A greater or lesser abundance of ice will affect the clouds’ lifetimes, their precipitation potential, and whether they behave as a blanket to warm the atmosphere, or as a bright shield to reflect sunlight, thus having a cooling effect.

It is yet another factor that climate models will have to consider, says study lead Dr Theo Wilson from the University of Leeds, UK.

"Our understanding of cloud formation is actually pretty poor, and we need to understand better how ice is made so that modellers can better represent it," he told BBC News.

Wilson’s team visited the Arctic, the northwestern Atlantic and the northeastern Pacific.

The scientists used a remote-controlled boat to trawl the top "microlayer" of these waters to see what sort of organic material it held.

Phytoplankton are clearly present, but these organisms, as small as they are, are really too big to be wafted high into the sky.

However, the plants also excrete matter. These "exudates", as they are known, are gel-like, and their scale is on the order of 0.2-0.02 micrometers.

This means they are capable of being carried skyward.

"This 'goo' is the sort of material that will get into the fine fraction of sea spray aerosol, which is the part of the sea spray that is going to make it high into the atmosphere," explained Dr Wilson.

His team shows that the exudates can become Ice Nucleating Particles (INPs) in the atmosphere.

"Exactly why they’re good at making ice is still not clear," said co-researcher Dr Luis Ladino from the University of Toronto, Canada.

"It could be because their structure is similar to ice; it could be because they have some affinity to have hydrogen bonds; or some other favourable chemistry at their surface. There are probably many components, and you can’t say it’s just one."

The effect of organic INPs is most relevant in those parts of the globe where desert dusts or pollution particles - long-recognised triggers for ice formation in clouds – are much reduced.

These locations would be the more remote regions on Earth, such as at the poles or in the Southern Ocean. Here, organic INPs could be playing a much more significant, and hitherto unrecognised, role in the freeze-up of clouds.

Modellers will need to be aware of this as they simulate future climate scenarios, says the team.

In the Arctic, for example, the well-documented reduction in sea-ice is opening up ocean water for longer periods of the year, allowing winds to more freely act on the surface to produce waves and sea spray. The open ocean is likely also to boost phytoplankton production with more sunlight getting into the top water layers.

"And in the Southern Ocean, a big fraction of the clouds exist in a super-cooled state with liquid water below zero degrees. So, if you had a situation where climate change causes a big increase in the flux of these INPs then that might start glaciating these clouds, which would have a knock-on effect on their optical and precipitation properties. These are the kinds of feedbacks we need to understand," said Dr Wilson.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos