Sometimes it takes a dejected, long-in-the-tooth boy band to teach a country about its own corporate values.

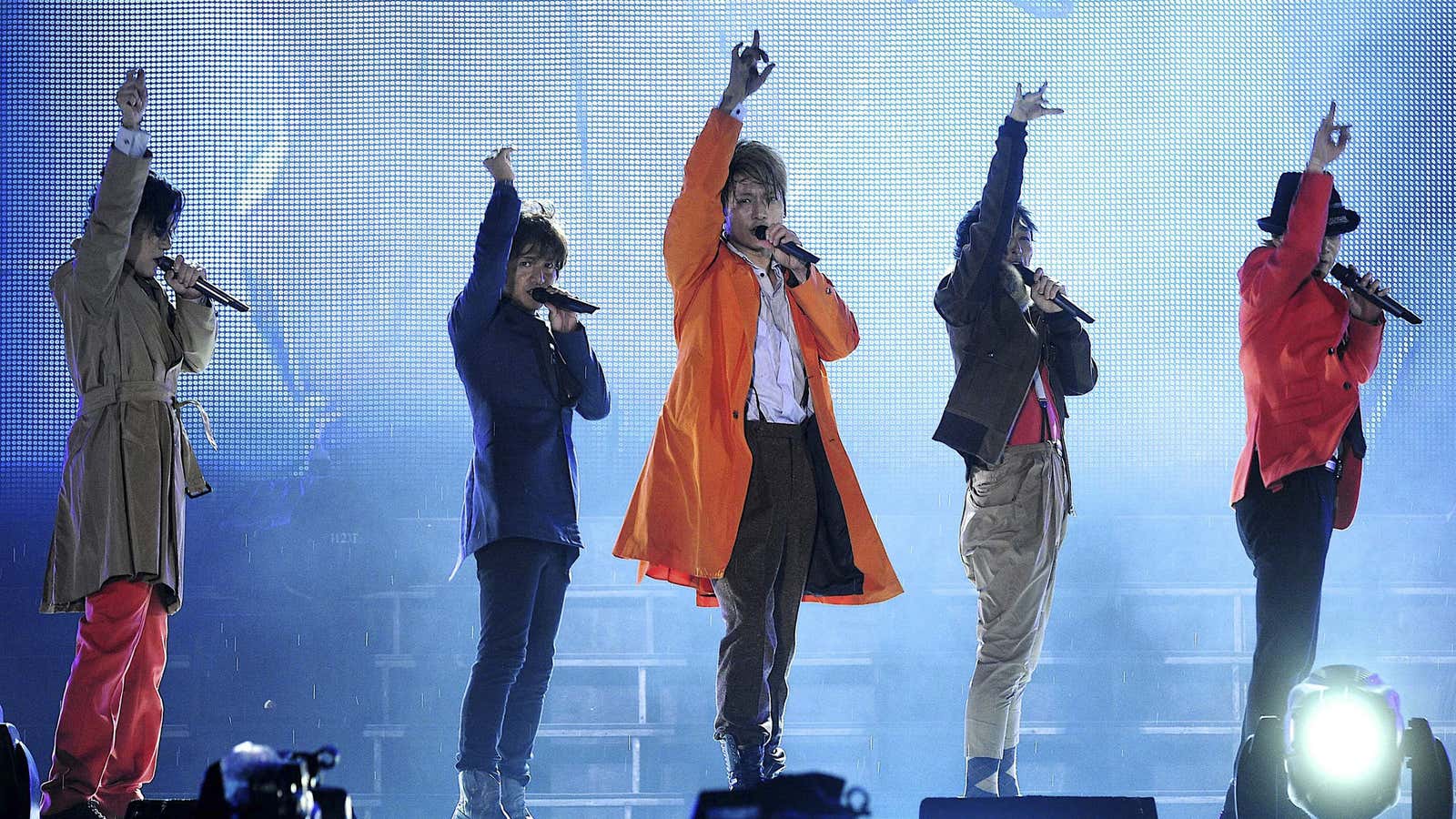

Japan was rocked in mid-January after tabloids reported that the hugely popular musical group SMAP would disband after 28 years together and more than 35 million albums sold. The media reported that four members of the group—Sports Music Assemble People, in case you were wondering—wanted to follow their longtime manager and pursue other creative outlets. The fifth, Takuya Kimura, wanted to stay with the band’s current talent agency, Johnny & Associates.

The breakup was not to be. Johnny forced out SMAP’s manager and brought the errant members to heel. In what some likened to a “public execution,” SMAP appeared on prime-time TV to issue fans an abject apology and promise more content together in the future.

News of SMAP’s attempt to break free reached the highest echelons of Japan. The day after SMAP’s apology aired, prime minister Shinzo Abe was asked what he thought of the outcome.

“Isn’t it a good thing for a group to stay together in response to their fans’ wishes and expectations?” Abe said on live TV.

Abe basically thanked SMAP for staying in a loveless marriage. But the incident brought up the peculiar dark side of Japan’s much-vaunted lifetime employment system. To paraphrase another entertainer recently in the news, Japanese salarymen are able to check into a job anytime they want. Few, however, really leave.

Japan Inc. tends to hire youngsters fresh out of college and pair them with a mentor to train them in the company’s own idiosyncratic ways. A new hire may spend years doing various jobs within the company before settling into his or her career.

There’s generally a reward for toeing the company line. Layoffs are almost unheard of in Japan. The system also breeds loyalty. More than 70% of Japanese employees who had been with their companies for at least five years will stay with the same company 10 years or more, according to a July 2015 report by Ryo Kambayashi. In the US, the figure is closer to 45%.

But as Johnny & Associates may have reminded its wayward charges, this investment can cut both ways. Employees unhappy with their present lot often find it extremely difficult to switch companies. Competitors do not want to take the time or the money to deprogram and then re-train a rival company’s castaway.

Indeed, the aversion can take on a moral tone. An ex-employee who “betrayed” one employer is unlikely to remain long at a new firm, the thinking goes. Job security for mid-career employees who jump ship is much lower than those who stay aboard, Kamabayashi’s report shows.

“This is a microcosm of Japan,” economist Ikeda Nobuo wrote on his blog of l’affair SMAP. “Companies adopt in bulk new graduates who don’t have specific skills, have them make photocopies and do so-called ‘mopping-up’ as on-the-job training. But such company-specific skills… are useless at another company.”

You can follow Ben on Twitter at @bjlefebvre.