Early on the last morning of CES, I found myself in a Las Vegas parking lot signing a liability waiver. I was there for a ride in a modified Ford Taurus carrying what could be the future of driving in America: a system that alerts drivers of potential accidents by talking to other cars.

After going through a number of scenarios, the driver of the Taurus pulled up to a simulated intersection. As the light changed and the driver went to pull through, an alarm sounded on the dash and he braked—just as another car in the demo, previously blocked from view by a parked container, shot through its red light.

In the real world, I would have been praying that the side-impact airbags would protect me. But in this version of a future US roadway, I was saved by radio signals sent by the car running the light, alerting the Taurus that a collision was imminent. “When you look at what causes accidents, about 90 percent are due to driver error,” said Michael Schulman, the technical leader for vehicle communications in Ford’s Active Safety Research and Advanced Engineering group. “Mostly drivers are distracted, or they just have bad judgment, or they’re impaired. So this is meant to be a first step to see how we can warn them. The car is always exchanging messages with other cars, and just in that rare case when I need it, I get a warning.”

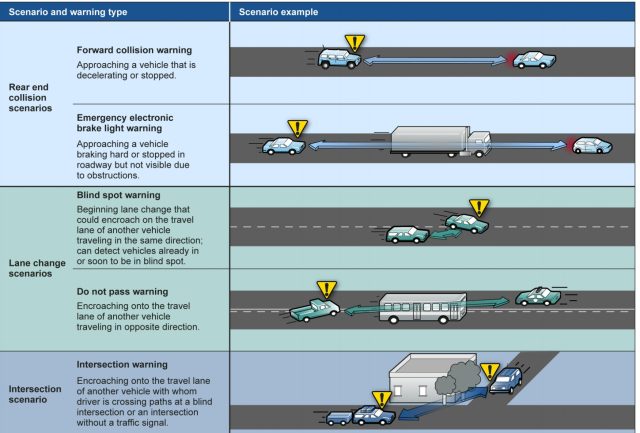

For the past decade, engineers from a host of auto companies—including Ford, GM, Honda, Toyota, Nissan, Daimler, Volkswagen Group, and Hyundai Kia—have been collaborating on the next step in vehicle safety. The system, called vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communications, or Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC), will allow cars to share data that can alert drivers to prevent the most common—and most fatal—multi-vehicle accidents on American roads.

The idea behind V2V is fairly simple, and it's based on technology that is already part of many new cars—it's just put together in a different way. Tested in a 3,000 car trial in Ann Arbor, Michigan over the past three years, the system uses a variant of Wi-Fi technology, GPS data, and vehicle data already collected by sensors in many vehicles to broadcast information that can warn other vehicles of a potential crash.

Just how soon this technology will hit the streets is still an open question, however. V2V is largely ready to go. And last year, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) seemed poised to mandate the technology in every vehicle. “NHTSA has to make a decision about [if it's] going to proceed toward a regulation that would require this on new cars,” said Schulman.

But that announcement has been held up. And part of the reason may be the leaks from former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden and the heightened awareness among both citizens and legislators of government surveillance. “Given what’s happened with the NSA,” Schulman said, “I think they felt, ‘If an announcement came out tomorrow, people are going to freak out.’”

The unfinished roadmap

Officially, the NHTSA would only issue the following statement on V2V: “The Department of Transportation and NHTSA have made significant progress in determining the best course of action for proceeding with additional vehicle-to-vehicle communication activities and expect to announce a decision in the coming weeks." Sources at the NHTSA say that the agency simply hasn’t finished all of the supporting work needed to support a decision on V2V yet.

When that decision does come, many in the industry believe it will be the first step in a much broader transformation of the nation’s transportation system. It will seed the creation of a network that not only prevents automobile accidents but also turns vehicles into data collectors. It would make it possible for traffic management systems to use vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communications to monitor congestion and deliver information to vehicles that improves traffic flow.

V2V and V2I are also seen as a necessity in the development of truly autonomous cars, allowing robotic vehicles to negotiate with each other to handle traffic flow. They could improve public transportation and provide countless other benefits to both drivers and governments.

But what worries some is that the system could be used to target “bad actors” on the highways, as they were referred to in a recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) report. Cars may become informants on drivers who speed or drive erratically, though the Department of Transportation says that the data will be purely anonymous and not used for those purposes.

There are already some with privacy concerns about location and other data being collected by automakers. Senator Al Franken of Minnesota recently wrote a letter to Ford executives requesting clarification on the company’s practice of collecting GPS data from vehicles. That request came after Ford Global Vice President of Marketing Jim Farley said that for drivers in Ford vehicles equipped with GPS and Sync, "We know everyone who breaks the law, we know when you're doing it. We have GPS in your car, so we know what you're doing. By the way, we don't supply that data to anyone." That came at CES, but Farley has since said that Ford does not track customers in their cars without their approval or consent. But the capability to do so still exists, as systems like Sync and GM’s OnStar collect more data behind the scene as part of navigation and safety features.

V2V ups privacy concerns because it essentially broadcasts a vehicle’s location and speed, as well as some information about where a vehicle has been previously, to anyone within range. And while Department of Transportation officials told the GAO that “V2V communication security system would contain multiple technical, physical, and organizational controls to minimize privacy risks—including the risk of vehicle tracking by individuals and government or commercial entities,” regulating who can use V2V data and for what would fall outside the Department of Transportation’s span of control. It would essentially require legislation by Congress.

And even after the NHTSA makes a decision on a way forward with V2V—if it decides there is a way forward—privacy concerns aren’t the only problems left to overcome.

Integrating V2V systems with new car designs may be relatively simple. The current platform for V2V is based on well-understood technology, such as automotive-grade GPS, radio technology based on the underlying standards of Wi-Fi, and event sensors that already report data such as a car’s pitch and yaw. A vehicle's current warning systems—lights, alarms, and in some cases “haptic feedback” systems such as vibrating seats—are already in production in vehicles equipped with anti-collision radar and other sensors. But integrating V2V into existing vehicles could be complex and expensive.

reader comments

109