When news broke that the mayor of Peoria, Illinois, had called upon his town's police force to shut down a fake Twitter account opened in his name; that local police had responded with search warrants against Twitter, Comcast, and Google; that they had at last raided a local home and seized four iPhones, four computers, two Xbox game consoles, an iPad, and a "large gold gift bag with five sandwich bags containing a green leafy substance;" that the homeowner hadn't created the account but was ultimately suspended from his job as a result of that "green leafy substance;" that Peoria's next city council meeting descended into outright acrimony over the heavy-handedness of the entire episode; and that the entire episode turned out to be a colossal waste of time and resources in which no one but the pot owner was ever charged with a crime—well, that's the moment at which a curious reporter files a public records act request to get a glimpse of how such a trainwreck got underway.

So I filed one—and the backstory I found was fascinating.

Could your town's mayor spark a police investigation into your activities that ends with town cops rifling through your mobile phone, your laptop, and the full contents of your Gmail account—all over an alleged misdemeanor based on something you wrote on social media? Not in America, you say? But you'd be wrong. Here, based on e-mail records provided by the city of Peoria to Ars Technica, is what that sort of investigation looks like.

Shut it down

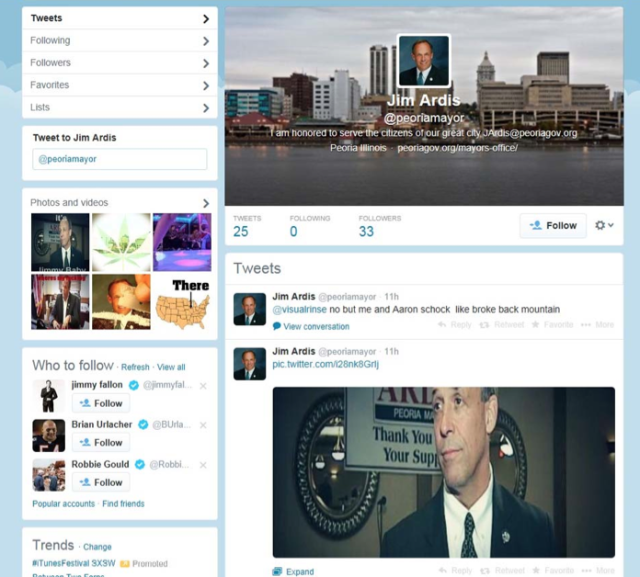

The name on the @peoriamayor account read simply "Jim Ardis"—the actual name of Peoria's mayor—and it featured Ardis' official city headshot. Its content was less than mayoral, however, most of it devoted to not particularly clever ways of suggesting that Ardis liked booze, drugs, and prostitutes and that he "woke up with pussy on my breath and blood shot eyes."

@peoriamayor was never popular; when it first came to the attention of city staffers, the foul-mouthed account was tweeting out bile like "I'm bout to climb the civic center and do some lines on the roof who's in?" to just 33 people and had been active for just two days. But it was public enough for someone to alert Patrick Urich, Peoria's city manager, who runs the city's day-to-day affairs and oversees its $169 million budget and 700 employees.

On March 11, 2014, Urich was working early. "Someone is using the Mayor's likeness in a twitter account," he wrote to Peoria's Chief Information Officer Sam Rivera at 6:06am. "It's not him. @Peoriamayor. Can you work to get it shut down today?"

Rivera filed an impersonation complaint with Twitter and got Ardis to scan a copy of his driver's license to convince the Internet service of the mayor's identity. While Rivera was working to get the account taken down and hopefully transferred to city control, Urich kicked off an ultimately more important line of action, asking Peoria Police Chief Steve Settingsgaard to put a detective on the case. Shutting down the account might be useful, but the ultimate goal was "to find out who might have set up this bogus account of the Mayor."

Urgency was the watchword; Settingsgaard almost immediately assigned the matter to Detective James Feehan of the Computer Crimes Unit, and Feehan just as quickly got to work. By 11:00am that morning, he wrote back to his chief that nothing in the @peoriamayor account added up to a criminal act—though "there are tweets posted by the individual which amount to defamation," he said. Should Ardis want to pursue that angle, he could do so through a civil lawsuit, but the police would have no involvement.

At 11:21am, Settingsgaard passed the bad news back to Ardis. No crime had been committed, and indeed, even the possible defamation angle raised by Feehan might be problematic. "I'm not an expert in the civil arena but my recollection is that public officials have very limited protection from defamation," he concluded. Case, apparently, closed.

But the @peoriamayor account continued to tweet away.

The next morning, Ardis e-mailed Settingsgaard about getting the account shut down. "Any chance we can put a sense or [sic] urgency on this?" he wrote. Three minutes later, City Manager Urich added, "Quickly please."

City Hall staffers were busy learning the hard way that Internet companies like Twitter don't "do" phone support, however. "I tried to contact Twitter today," wrote the assistant city manager that evening, as he, too, requested that the police get more involved, "but there is literally no one to answer the phone except a machine. That machine tells you that they don't do support over the phone. There also seems to be no way to check on the status of a case. But maybe they will respond to the Police more than [Sam Rivera] and the Assistant City Manager."

Back at police headquarters, Detective Feehan began getting more heat from his boss. "Jim, do you have a way to make this happen faster?" Settingsgaard wrote.

But, like Rivera, Feehan had already filed an online impersonation complaint with Twitter support, and he could do little else to make Twitter move more quickly. As Settingsgaard noted later that morning in an e-mail to Mayor Ardis, "Feehan is working on this and he has thus far been unable to penetrate Twitter's wall. The telephone numbers lead to dead ends and it keeps pushing you back to online reporting."

What Feehan could do with his downtime was further investigate Illinois law. If the cops could convincingly claim that a criminal act had taken place, they had far more resources to bring to bear on the matter: subpoenas, search warrants, and even arrests. Feehan combed the statutes and, remarkably, found a new Illinois law that had gone into effect in January 2014.

720 ILCS 5/12-2 covers "false personation" and bans people from pretending to be police officers or firefighters. Tucked in its many provisions is this broad one: "A person commits a false personation if he or she knowingly and falsely represents himself or herself to be… a public officer or a public employee or an official or employee of the federal government." Could the @peoriamayor account be an act of "false personation"? It wasn't a major charge—just a misdemeanor—but it was a crime, which is all that mattered.

Settingsgaard and Feehan did plan to check with the local state's attorney to "make sure we are interpreting and applying this new statute correctly," but both thought they were in the clear. All they needed was for Ardis to give the word that he wanted to press charges, and the muscle of the state would start to flex.

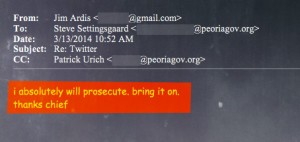

On March 13 at 10:52am, Ardis wrote back to Settingsgaard: "i absolutely will prosecute. bring it on. thanks chief"

reader comments

219