The League of Extraordinary Black Gentlemen

"As an upper-middle-class black male, I am seen as part of the solution class tasked with rescuing my nation from its problem and my race from itself."

In “Strivings of the Negro People,” the seminal 1897 essay published in The Atlantic, the renowned writer W.E.B. DuBois succinctly captured the issue that’s haunted black America since before the ink dried on the Declaration: “How does it feel to be a problem?” These precise words were never spoken aloud, he explained. But they were implied every time a well-meaning white person praised an “excellent colored man” from his hometown, or went out of his way to mention his service in the Union Army. Addressing the hidden question, DuBois wrote:

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self.

For black men in America, this question has changed only slightly. Though never directly posed to me, it is enunciated in the glinting smirk of approval when people learn of my academic and professional credentials. It comes through in the nod of surprise when they learn that my black father was biologically mine, married to my mother, and as present today as he was throughout my entire childhood. It’s coded in compliments like “articulate” and “well-mannered”—neither of which is truly praise for an adult. The descendant of the DuBois question now stands as this: “How does it feel to be the solution?”

If the late 19th-century problem was that black Americans—recently emancipated and fully unassimilated—were an ill fit for full citizenship in the nation they called home, the 20th-century solution was to allow the gifted among them to develop their talents and then teach the others how to properly comport themselves.

DuBois called them the Talented Tenth—a league of extraordinary black gentlemen who would serve as an inspiration for maladroit blacks and a catalyst for acceptance by the nation’s white majority:

The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst, in their own and other races.

When America began to slowly emerge from under the cloud of Jim Crow, the idea was that fair access to the ballot box, integrated education, dignifying work, and safe housing would create a black population prepared to participate in the American experiment. The exceptional ones—the solution—would lead their people in the pursuit of these goals, steadily ascending the staircase Langston Hughes had described a generation earlier:

Well, son, I'll tell you:

Life for me ain't been no crystal stair.

It's had tacks in it, And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor—Bare.

But all the time I'se been a-climbin' on,

And reachin' landin's, And turnin' corners

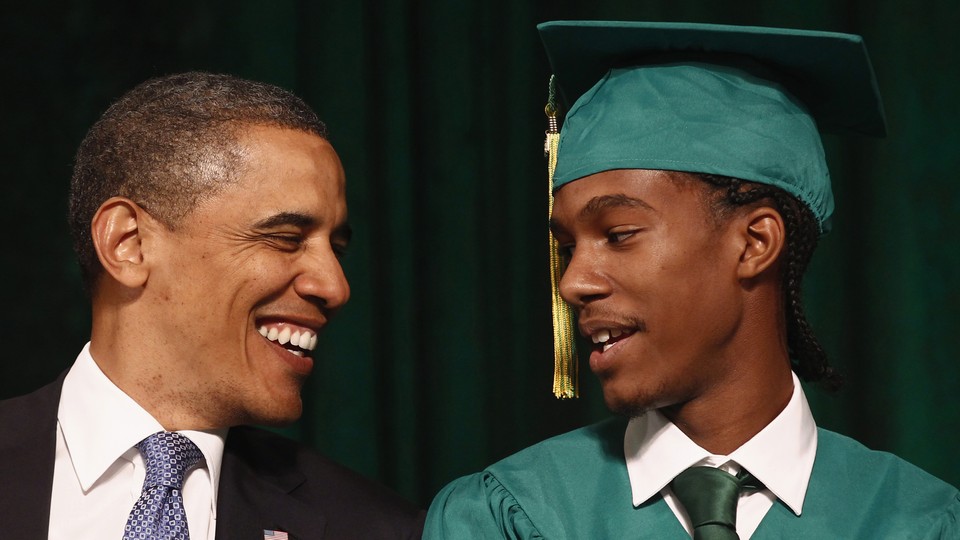

Since then, years have passed—ten, twenty, fifty. Today, blacks are more educated than they’ve ever been and occupy more of the middle class than they once did. The electorate has desegregated to the point where black voter turnout rates surpassed white for the first time in history in 2012. There are black Fortune 500 CEOs and media moguls, politicians and white-collar professionals, who have tremendous influence on American society. And yes, even our president is black. These are direct results of the value the community placed on elevating our exceptional members and making blackness palatable to the whole nation.

In the 21st century, the Tenthers—the solution class DuBois envisioned—have arrived. These college-educated, middle-class black folks have left the South and inner cities to settle in suburbia, and fashioned an identity as bound up in class as it is in race. But like DuBois himself, they struggle with a double-consciousness—a twoness that makes it possible for them to enter predominantly white spaces while still holding positions of esteem in spheres of blackness. They move about both comfortably, but don't fit neatly into either.

This is my reality: As an upper-middle-class black male, I am seen as part of the solution class tasked with rescuing my nation from its problem and my race from itself. Yet, ever since my childhood, I’ve been held at arms-length by two cultures. Many of my black peers were bused in from the other side of town; after hearing my diction and learning I lived in a suburb replete with green lawns, two-car garages, and debris-free streets, they labeled me an Oreo, a well-worn slight indicating blackness on the outside and whiteness on the inside. Meanwhile, as the only black kid in my neighborhood or honors classes, I was called a “raisin in a bowl of milk.” Some of my white friends invited me to their homes for parties and sleepovers, but introduced me as their “black friend Teddy.” I was never black enough for the ’hood, but always too black to exist without a race modifier in my own neighborhood.

As adults, we Tenthers joke about having our “black cards revoked.” And in the next breath, we trade stories of professional connections that masquerade as interracial friendships—so dependent on code-switching that we envision them telling each other, “It’s almost like he’s not really black.”

Both sides make the same basic claim about us: we are exceptional. But they don’t mean this in the usual way, as an objective observation of personal excellence or meritocratic achievement. Instead, it’s an assertion that sets us apart from the rest of black America, implying that we’re oddly different and a little less Negro than the others. We’re anomalies wherever we go, considered less authentic than the brothers in the inner city and certainly less-than-totally acceptable to the larger society. The solution is at hand, and yet, the problem remains.

And what have we accomplished? Segregated schooling and housing practices still exist, though they are now economic and social conditions instead of legal enforcements. The Tenthers haven’t been able to change the rigorous policing and biased sentencing that have imprisoned vast swaths of our communities, eroding families in the process. Despite the economic success of our privileged circles, black wealth, income, and unemployment are perpetually at recession and depression rates. Key victories for voting rights are slowly being rolled back. The results of all this include children who fall behind in school before they are even enrolled, health disparities made worse by poverty and racism, and public policy that maintains systemic inequalities.

The reality is, of course, we Tenthers were never the answer to begin with. We bought into the idea that education, personal fortitude, and hard work would be enough to overcome history and raze barriers to equality. But in the process, we’ve set ourselves apart from the two communities we were created to bring together.

How does it feel to be a solution? It feels like social carpetbagging, always code-switching to blend in with whichever environ we happen to be in. This is more than just a social survival skill; it’s become a matter of identity. There is no turning it off, only tuning the rheostat. We will never completely fit in America, and will always be confronted by preconceived notions. DuBois charged us with relieving the burdens of “an historic race, in the name of this the land of their fathers' fathers, and in the name of human opportunity.” Yet, we are an exercise in insufficiency.