America's growing force of fast-food workers may soon have a challenge on their hands greater than the inability to earn a living wage from full-time work in the industry: Much of the work they are currently doing could be taken over by machines within the coming decade or so.

While the full automation of fast-food cashiers isn't here just yet, researchers and those in the business say it's only a matter of time before ordering and payment become primarily self-service. Mobile apps and touchscreen kiosks that are already transforming the business will likely become more appealing as wages rise, and will probably take over even if they don't.

Restaurants are keeping a close eye on labor costs. Los Angeles, Seattle, and San Francisco all recently approved increasing their minimum wages to $15. On July 22, a New York wage board recommended gradually increasing wages for fast-food workers in New York City to $15 by Dec. 31, 2018, and to $15 for the rest of the state by July 1, 2021. It now awaits approval by the state's labor commissioner.

"I fully believe that it will seem crazy, even just two or three years from now, that we used to wait in long lines until we got our turn, and then told [a cashier] what we wanted, and had them punch it into a machine for us," said Noah Glass, founder and CEO of Olo, which makes mobile ordering and payment technology for restaurant chains including Five Guys and Chipotle.

The current system seems particularly outdated, he said, "in an era where 75%, 80% of us have supercomputers that are location-aware and web-enabled on our bodies at all times."

Industry groups are keen to remind workers that demands for higher pay are taking place just as labor-saving technology is making its move on a core part of their work. "You can have a $15 [minimum wage] or you can have the same number of job opportunities you have now, but you can't have both," said Michael Saltsman, research director for the Employment Policies Institute, a business-backed think tank.

A full-page ad the organization took out in the New York Post in June was less coy. "Meet the new minimum wage employee," read the text over a photo of a touchscreen ordering kiosk.

Amid these declarations, many of the country's largest fast-food chains, including Starbucks and McDonald's, have rolled out or are in the process of developing smartphone apps and in-store kiosks that shift work from the cashier to the customer. It's still early days, but if consumers show in large numbers they're willing and happy to place orders themselves — primarily as a matter of convenience — even a $7.25-an-hour worker under today's federal minimum wage could become a questionable expense.

As wages increase, "franchisees have to find a way to pay for those extra costs," Dunkin' Brands CEO Nigel Travis told BuzzFeed News. Operators of the company's Dunkin' Donuts and Baskin-Robbins outlets can offset higher labor expenses through "some form of automation" like new ordering technology, adjusting supply chains, or increasing sales, he said.

Another option, less popular with customers, would be raising menu prices. Just this month, consumers saw increased labor costs lead to higher prices at Starbucks and Chipotle.

But despite doomsday predictions from industry, labor leaders are not yet raging against the machines. Representatives from three groups that represent waitstaff and retail workers — the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC), and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) — said their members are not overly worried about the robots on the horizon, at least for the moment.

"Our membership is most concerned with wage theft, living wages, stable, full-time hours, and safety right now," said Maria Myotte, national communications coordinator for ROC, an alt-labor organization representing 13,000 restaurant workers.

Myotte described threats of automation as primarily a "scare tactic" used by the National Restaurant Association and other business interest groups. Others in labor say they're an indirect version of telling employees they'll be fired as a consequence of pressing for higher wages.

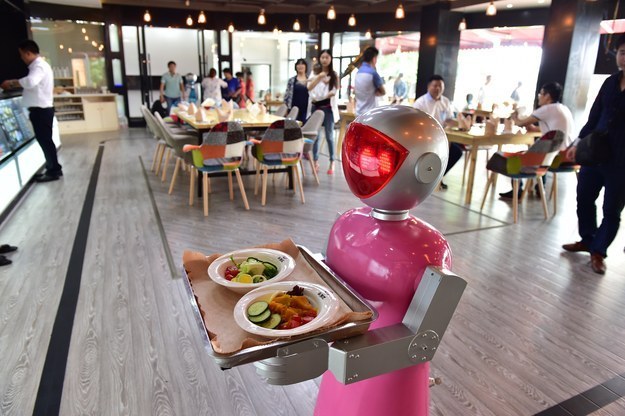

While some workers have seen tablets rolled out in places like Olive Garden, Myotte said so far screens are "augmenting workers, not replacing them — just changing what it means to be a server or host."

In retail, the slow rise of customer self-checkout hasn't yet generated grievances or notable job loss, according to Janna Pea, communications director for RWDSU, which represents 100,000 workers in retail and grocery stores, among other sectors. Tech-related worries among workers mainly stem from the use and abuse of scheduling software, in her experience.

And SEIU President Mary Kay Henry said she has only heard dire predictions about automation "from electeds, from other employers, and from media people," rather than workers themselves. For the SEIU, automation isn't something to fear, said Henry, so long as "basic respect and dignity for our humanity" are maintained as new technology enters the workplace.

Technological transitions like this happen gradually, and many believe they're inevitable regardless of pay rates. "People shouldn't get the impression that if we don't raise the minimum wage, the robots won't come," said Martin Ford, an entrepreneur and author of Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. "They're coming either way, and it's mostly a question of whether the technology is available."

Perhaps the most mature example of displacement in restaurants is the pizza business, where the longstanding convention of ordering by phone had prepped customers to order by app. Domino's now gets about half of its orders digitally, meaning from its website or app, and at Pizza Hut the rate is about 40%. At both chains, the share of digital orders has been rising.

For Domino's, the digital ordering system lets customers design and save their favorite pizzas for easy repeat orders, boosting the frequency with which they order. That higher frequency "has a much greater benefit for us than nominal ticket increases and labor cost reductions," said CEO Patrick Doyle on a recent earnings call. The system, he said, "is clearly a big part of what is driving our same-store sales growth."

That shift is happening in other restaurants, and executives (many of whom say they support a minimum wage increase) have framed the changes as improvements to the "guest experience" rather than a rethink of labor.

In April of last year, Panera announced it would bring self-service kiosks and mobile ordering to all its locations by spring of 2017. Stores will eliminate one or two cashiers each, though Panera CEO Ron Shaich told BuzzFeed News that the new technology "is not about efficiency." Since implementing the $42 million system, Panera has reassigned workers to monitor order accuracy, as the company found customers are more likely to customize sandwiches when ordering via an app.

By placing orders themselves, customers eliminate errors — and, if one orders via mobile, meals are often ready for pick up by the time one arrives at the restaurant. "We save you time, and we give it to you exactly how you want it," Shaich said.

It's this combination of advantages, in addition to potential labor efficiencies, that makes ordering apps so compelling. At Starbucks, about 20% of customer spending now comes via its mobile app, a number likely to rise as it rolls out full mobile ordering this year.

"This is just the beginning," Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz told BuzzFeed News in March, predicting that mobile ordering and payment would become a central part of the fast-food experience in the coming years. "I would say on the macro level, you can't be in any industry today, let alone a consumer business, and not integrate the business through the lens of seamless technology."

Trials of self-service technologies have so far only encouraged restaurants to move ahead with the systems, and they're discovering unexpected benefits of handing over the ordering process to consumers.

At Taco Bell, customers ordering through the app were more likely to request add-ons like onions, sour cream, nacho cheese, and creamy jalapeño sauce. The average bill for these customers was about 20% higher than orders placed via a cashier.

Higher costs "puts pressure on all aspects of your business. I don't think you can just pass along the increased cost. And for Taco Bell I want to be the value leader," Taco Bell CEO Brian Niccol told BuzzFeed News. The app "is a way for people to take a price increase with us not actually increasing prices... Mobile, digital, and new avenues like catering and delivery are places where the check is higher, which helps. No doubt about it, it helps."

Cinemark theaters learned that moviegoers eat more popcorn thanks to higher rates of impulse-buying at self-service machines, which typically don't have lines — or a human judging you for a decadent order. (The shame is real: Customers using ordering kiosks elsewhere have been found to order dessert more often. They also request more liquors with difficult-to-pronounce names, when there's no risk of mis-speaking.)

Such promising developments have McDonald's rolling out build-your-own-burger kiosks at 2,000 U.S. locations. Custom-made burgers cost more than the typical McDonald's offering and let diners pile on extras they might not typically ask a cashier for.

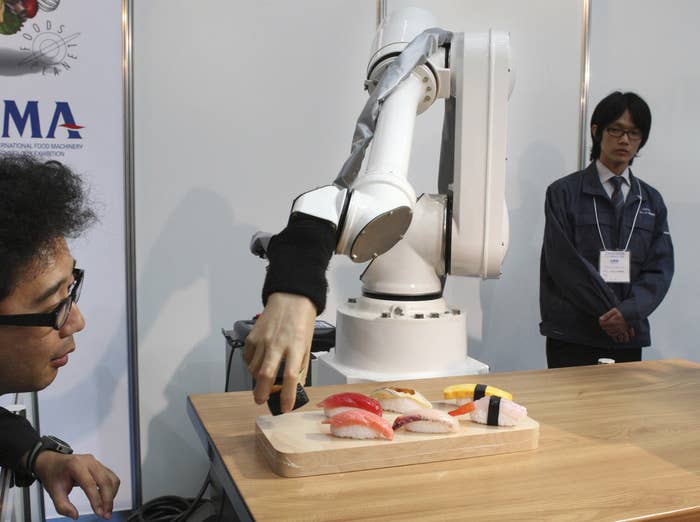

"As technology becomes cheaper and more available, especially consumer-facing technology like tablets, it's going to become pervasive," said Rajat Suri, CEO of E la Carte, which has installed more than 65,000 tablets in restaurants including Applebee's. "We've seen it in every other industry, airports, groceries, banks....I think it's reasonable to expect this to happen in restaurants as well."

The prospect of the fast-food cashier becoming as much of a relic as the taxi dispatcher or the bank teller complicates efforts to put such workers at the center of a national movement to raise wages. But one upside to workers organizing for higher wages is that their actions create unity, whether or not they ultimately result in a formal union. Such organization may help workers have more of a say in technology's introduction, said Stephanie Luce, associate professor of labor studies at CUNY.

Technology could make dangerous jobs safer, or ease arduous work, she said. A slow phase-in could shift workers' focus to better food and better service, rather than tedious order-taking and credit-card swiping, benefiting both consumers and workers. Just as few today mourn the mechanization of back-breaking agricultural labor, the decline of the order-taker could aid in the rise of a better quality of restaurant work.

"We would want to encourage innovation," said Mary Kay Henry, the SEIU president, "and figure out other things that people can do with their labor that would be more satisfying."