Opinion The fading memory of amity

As Sikhs protest in Islamabad, Pakistan is forgetting what the past is trying to say.

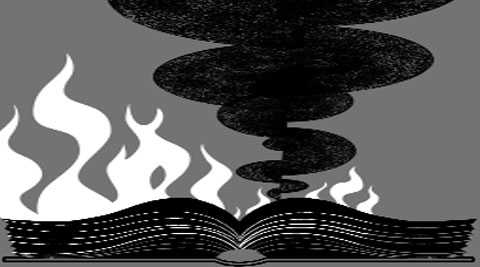

The media discussed the protest, rather than the cause of the protest, simply because a self-centred state could not understand why Sikhs from Nankana in Punjab were so agitated about the violation of Hindu temples in Sindh and referring to the desecration of their holy book.

The media discussed the protest, rather than the cause of the protest, simply because a self-centred state could not understand why Sikhs from Nankana in Punjab were so agitated about the violation of Hindu temples in Sindh and referring to the desecration of their holy book.

On May 24, 2014, about 300 Sikhs from Nankana Sahib came to Islamabad and entered the parliament to protest against the desecration of their holy book, the Granth Sahib, in Sindh and remained on the premises for several hours before being driven out by the police.

The media discussed the protest, rather than the cause of the protest, simply because a self-centred state could not spare time to understand why Sikhs from Nankana in Punjab were so agitated about the violation of Hindu temples in Sindh, referring to their holy book.

At the Karachi Press Club, Pakistan Sikh Council (PSC) patron Ramesh Singh demanded the following week that the government — comprising of the secular PPP and MQM — investigate why copies of the Sikh holy book were burnt inside Hindu temples across the province, including in Sukkur, Dadu and Shikarpur, Hyderabad, Badin, Larkana and famine-hit Tharparkar. There are only 20,000 Sikhs in Pakistan; Hindus, mainly concentrated in Sindh, number 2.5 million.

On March 31, the daily Dawn of Karachi wrote a staid editorial, half-guessing who could have done the desecration and appealing to the Sindh government to do something about it. It did not touch the issue of the Sikhs for some reason and could not connect the Granth Sahib to the violated Hindu temples. There was a moment of mystification in the country and then all was quiet again till the next outrage against the fleeing Hindus.

The tide of Islam has already reached Sindh where the public memory of Hindu-Muslim amity is still fresh. But the knowledge of Nanakshahi Hinduism is fading and temples arouse hostility among the new generations.

Sindhi scholar Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro reminds his compatriots that an Udasipanth cult was founded in Sindh by Baba Srichand, the elder son of Baba Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh religion: “It is believed that he visited Thatta and other towns of Sindh. In order to commemorate his visit, a large darbar was built in Faqir Jo Goth, a village that lies 5 km away from Thatta.”

About the presence of the Granth Sahib in Hindu temples, it is claimed that the temples of Udasis are known as darbars while Nanakshahis call them tikano. Both give the Granth Sahib the pride of place in their temples along with pictures of the Hindu pantheon.

A Sikh visiting Gujarat narrates: “When I first came to Gujarat (carved out of old Bombay State in 1960 and four times bigger than present [Indian] Punjab) in 1965, I was rather surprised to see Sindhi gurudwaras or mandirs named ‘Guru Nanak Darbar’ even in small towns. A large number of Sindhis migrated to Gujarat from the adjoining Sindh province after Partition. They were devotees of Guru Nanak Dev and Guru Granth Sahib. During the last 45 years, I find that many of these Guru Nanak Darbars have disappeared.”

Indian scholar Kothari too records the Hindu migration to Gujarat. Ships from Karachi arrived at the ports of Porbander, Veraval and Okha on Gujarat’s coast. Movement towards Gujarat also happened indirectly, especially via Rajasthan, when Sindhis arrived from Mirpurkhas. These Sindhis looked “Muslim-like” to the locals: “The Hindus of Sindh were not quite the most suitable examples of orthodox Hindus, as they were a meat-eating community in a largely vegetarian region.”

BJP leader L.K. Advani, in his autobiography My Country, My Life (2008), writes: “The Advani family belonged to the Amil branch of Sindhi Hindus. Traditionally, the Amil was a revenue official who assisted munshis in the administrative set-up of Muslim kings. It was one of the two main divisions of the Lohano clan which was linked to the Vaishya (business) community. In time, Amils came to dominate government jobs and professions in Sindh. Generally speaking, Hindus in Sindh had a strong tradition of revering the Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred scripture of the Sikhs, Guru Nanak and other Sikh gurus. There is an interesting story behind this strong Sikh influence.

“It is believed that the city of Hyderabad was destroyed by a fire in the mid-eighteenth century. The Muslim ruler of Sindh was looking for someone who could rebuild the city. His officers mentioned a person named Adiomal (founder of the Advani clan) living near Multan (now in Pakistan).

Satisfied with his credentials, the king offered him an attractive remuneration for rebuilding the city on a new site. Adiomal was a devout follower of the Guru Granth Sahib.

“Therefore, he told the king: ‘I shall rebuild this city only if you first allow me to build a gurudwara where I can read the Granth Sahib without any Muslims harassing me.’ The king agreed. For completing the task, Adiomal sought the cooperation of his fellow Amils — a civil engineer named Gidumal (of Gidwani clan) and a financial expert named Wadhumal (of Wadhwani clan). Soon Hyderabad had a large Amil population settled along Advani, Gidwani and Wadhwani streets.”

Many Gujarati-Sindhi Hindus are Lohano, descended from Loh, the younger son of Ram. There was a time when most Hindus of Sindh claimed they had come to Sindh from the north, the territory of Loh. Everyone knows that Lahore is named after Loh.

L.K. Advani would be aware that the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, was from the Lohana of Sindh. Jina was a common name among Gujaratis and also among Muslims who started settling in Gujarat in the 12th century. Many Muslims (Bohra, Khoja, Memon) included local converts, all claiming to be from the Lohana Rajput tribe.

The rise of Jainism in Gujarat took place under the Rajput dynasty of the Chalukyas (AD 942-1299), many of this faith rising to high ranks and counted among the tradesmen, shaped by the only port, Surat, on the western coast of India. Ismaili-Bohra scholar Asghar Ali Engineer once told me that Ismaili-Musta’ali Muslims called themselves Bohra after they were well-treated by a local Gujarati ruler named Vohra.

Jinnah’s Poonja family had its origins in Gujarat and could have grown to admire the non-violent Jains, also called Jinas. In Maneka Gandhi’s book of Hindu names, a dozen names starting with Jina or Jeena are all identified as being of Jain origin, meaning “victorious”. Jinnah’s father was named Jinabhai. Jinnah took his new spelling in his own eccentric fashion. From Jina, he could become Janah, which in Arabic means “wing”, and that would have been just right for the consumption of the Muslims. But he didn’t do that. He also made Jina or Jeena into Jinnah, a kind of “no” to both the communities at loggerheads in India.

As the Sikhs of Nankana Sahib protest in Islamabad, the Muslims of Pakistan are in the process of forgetting what the past is saying to them. “Nation-building” can be deceptive because of the misapplication of language. The Taliban ruled Afghanistan and destroyed Afghan culture, calling it nation-building through Islam. Now they are doing it to Pakistan in Sindh.

The writer is consulting editor, ‘Newsweek Pakistan’