The Traveling Salesmen of the Nuclear-Industrial Complex

A new book collects their business cards in all their well-designed detail.

How do you tell the story of nuclear weapons?

One way is to focus on the vast system that produced them. “The atomic industry is a continental industry, with global implications,” says Matthew Coolidge, the director of the Center for Land Use Interpretation. It was “an industry that was built very quickly, from Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to Hanford Site, Washington, basically creating a federally subsidized machine that was landscape in size and continental in scale.”

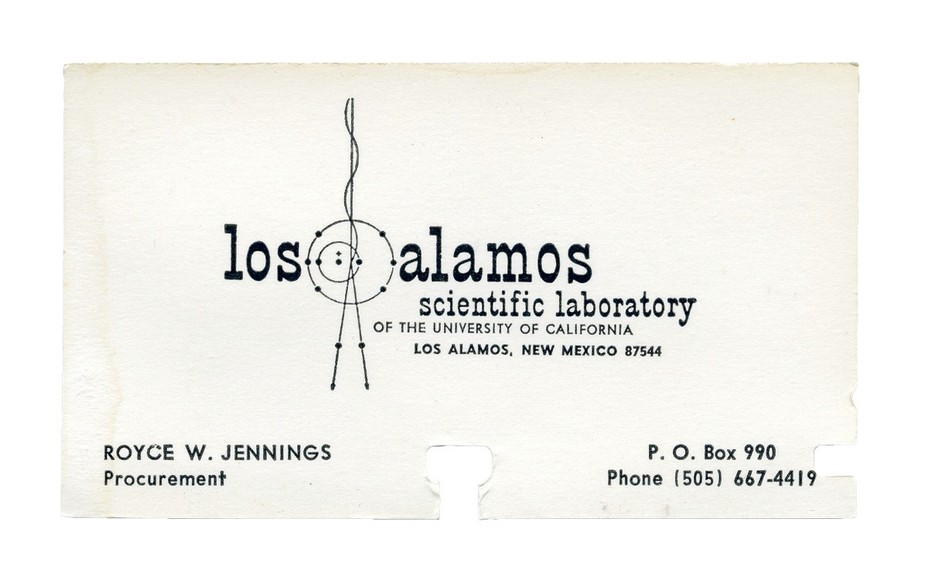

Another way is to focus on the people who worked inside the system—salesmen who traveled to Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, one of the two laboratories that worked (and still works) on nuclear weapons, and see what they left behind:

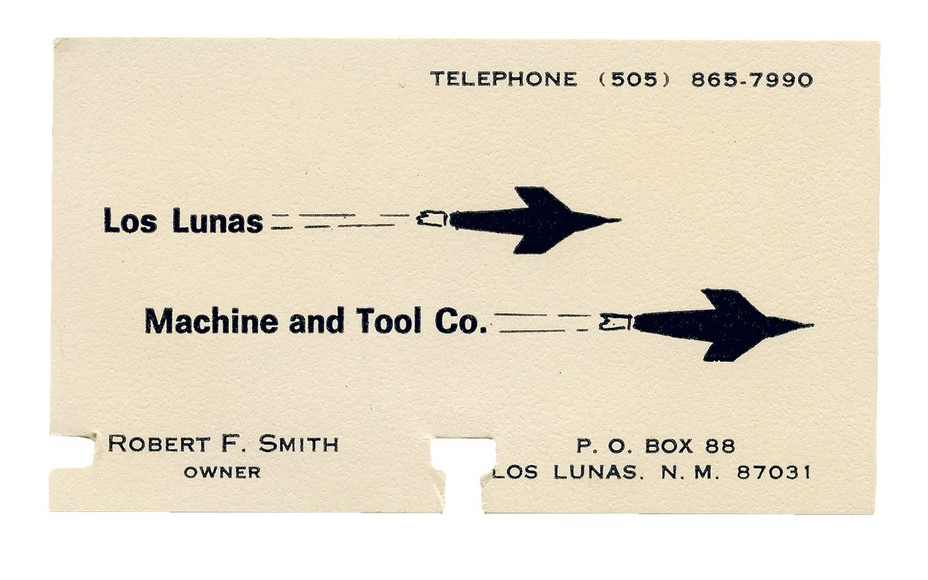

That’s the tack taken by Los Alamos Rolodex, a new book from the Center for Land Use Interpretation. Rolodex reproduces more than 100 calling cards left at the national laboratory between 1967 and 1978. Coolidge wrote the introduction to the book, and he also founded the Center, which has offices across the American West and focuses on “human interaction with the earth’s surface.”

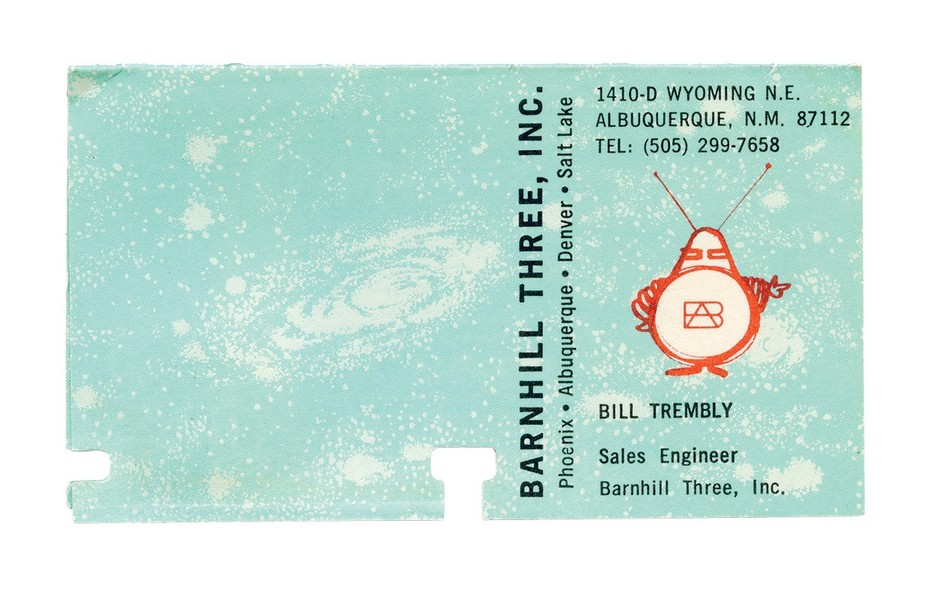

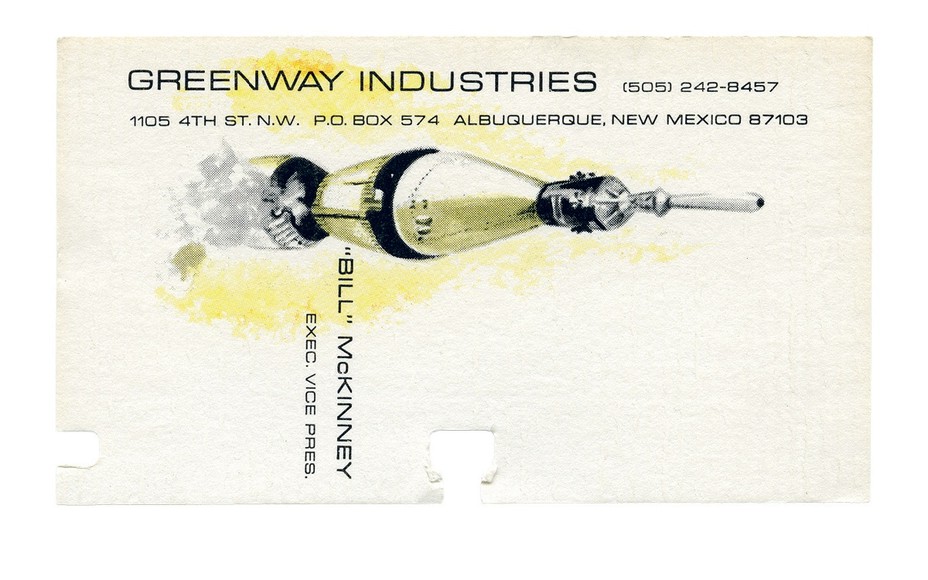

Though its concept might sound a little odd, flipping through Los Alamos Rolodex turns out to be oddly pleasing. Coolidge calls the cards “raw material”: not stories in themselves, but pointers to hundreds of individual stories. In a way, Los Alamos Rolodex takes the two approaches at once: We see people as professionals, glimpsing both them as individuals and their role in the machine.

And in book form, the cards feel like seeing a URL that can’t be followed, or coming across a bibliography that cites only made-up books. The cards reference a reality that no longer exists, but they also let you glimpse the human network that gave rise to the atomic industry.

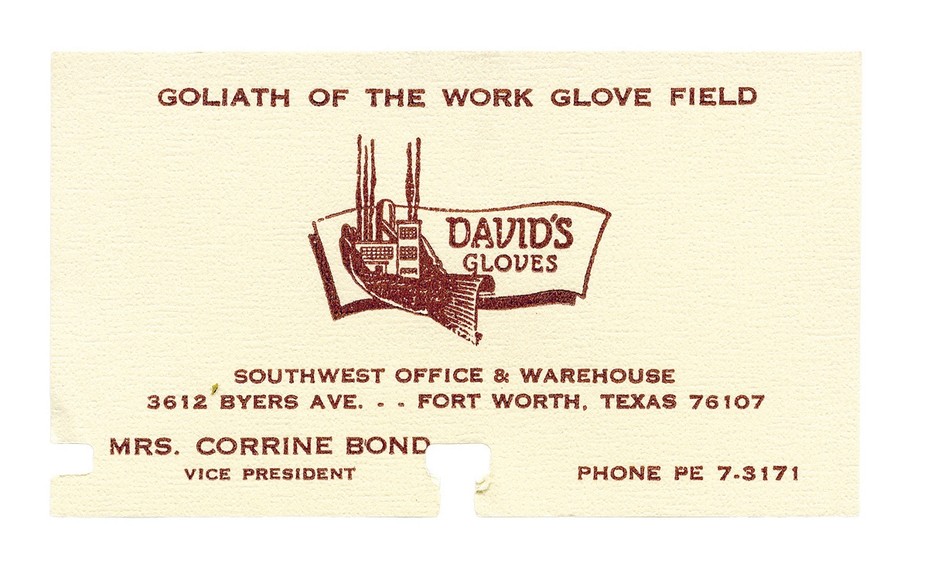

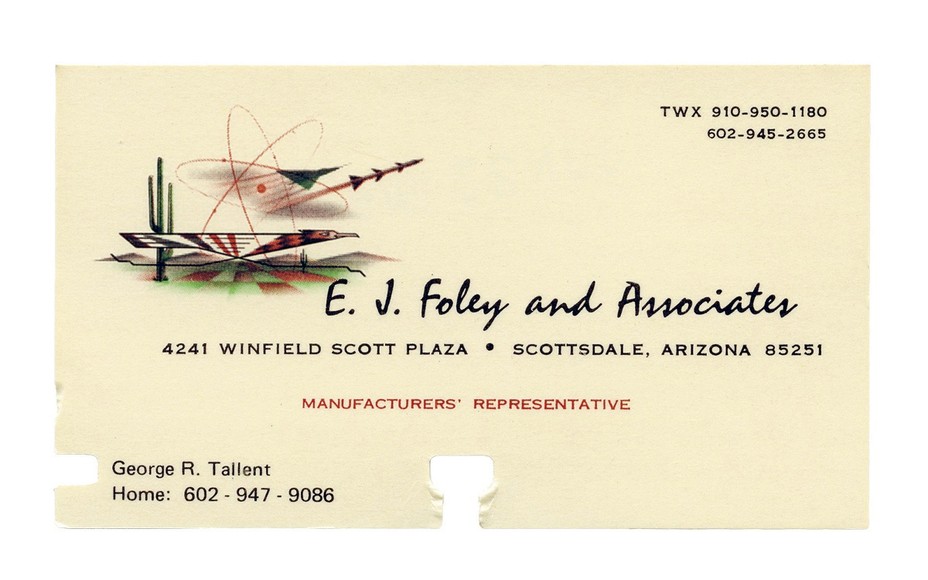

On top of that weighty goal, Rolodex is also gorgeous. This is midcentury American design—the school of flat sans-serifs and frontiers of white space—in all its regional peculiarity. No card looks quite like the others, and even cards from the most seemingly mundane companies boast a quirky logo or turn a phrase in an odd way. Coolidge told me that he was fond of the card from David’s Gloves, “THE GOLIATH OF THE WORK GLOVE FIELD”:

The cards came to the Center via Ed Grothus, an anti-nuclear activist who operated a museum cum military-surplus store for decades in the city of Los Alamos. Grothus and his wife ran that store—called “the Black Hole”—out of an abandoned Piggy Wiggly supermarket. Visitors could walk through the shelves, full of old scientific equipment and used computer arrays, with shopping carts, but only some of the items were on sale.

But while the cards sat in the Black Hole, no one much noticed them. Only after Grothus’s death in 2009, when most of the contents of the Black Hole were being sold off, did they catch the attention of Aurora Tang, an artist and program manager at the Center, Coolidge said.

That rolodex contained hundreds of cards. Not all made it into the book, but more than 500 are on display at the Center’s Los Angeles gallery.

“We did incidentally look up and call the numbers, and some of the companies are of course well known and are still extant. Some disappeared or were bought by other companies,” Coolidge told me.

But the cards do not only depict an entirely lost world. Much of the computer equipment appears to have come from companies based in Silicon Valley. (Many of those firms actually made silicon back then.) Siliconix Incorporated, which left calling cards at Los Alamos, was based in Sunnyvale, California. A few years ago, Atlantic contributing editor Alexis Madrigal deduced that the “center of Silicon Valley” was in Sunnyvale.

Some cards, meanwhile, boast even more familiar tech industry names:

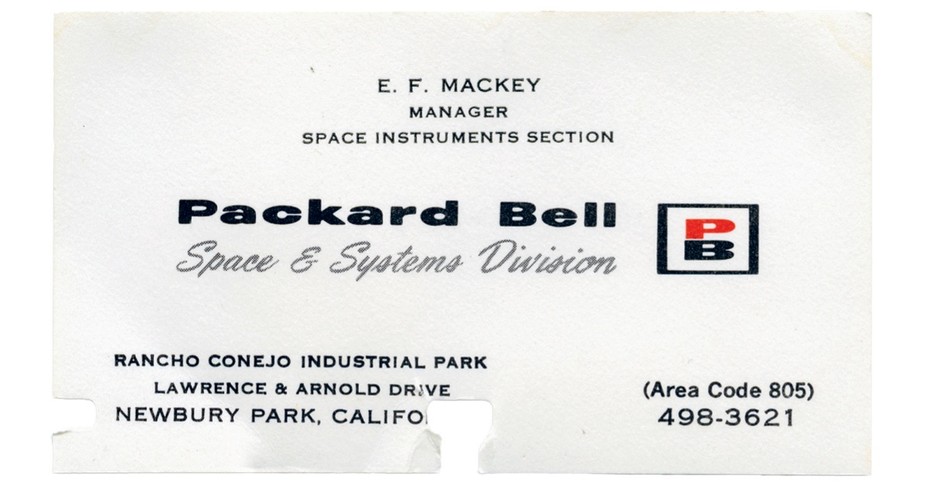

Others seem quite pleased about their proximity to the military-industrial complex:

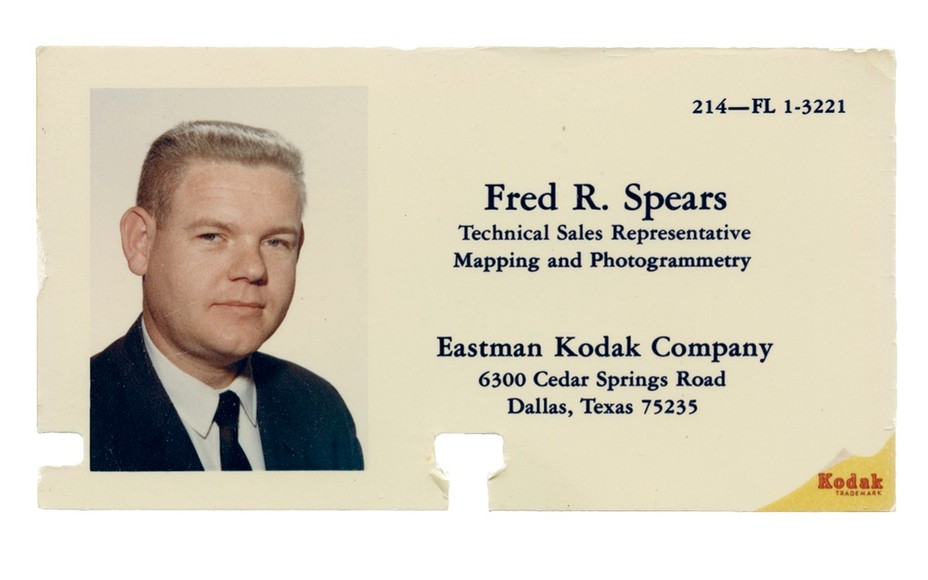

“I love the human quality, because each of these cards is very personal,” Coolidge said. “So you have even, in some cases, people on them—the two Kodak cards we included had pictures of the sales representatives. Kodak is of course well known for creating a consumer photography industry, but it was also deeply involved with government work at every level.”

You can also find other companies involved in the vagaries of pre-computational electric memory, like this one hawking magnetic tape:

I asked Coolidge if we should draw any conclusions about the names on the cards. Were these salesmen complicit, somehow, in the creation of one of the most fearsome weapons of all time? He didn’t think so.

“Like anything that happens in this country, [the atomic industry] was done by people who are trying to make a living,” he told me. “I think the people on the cards are just representatives of a larger phenomenon they couldn’t really do anything about. I don’t think there’s any kind of culpability or involvement—at least, we’re not trying to suggest that.”

“Each card is a mirror in a way, but each card is also a star gate or wormhole that represents a whole series of questions,” he said.

Maybe the only pat conclusions we can draw are smaller, tidier, then—like noticing that only one woman’s name appears on the more than 150 cards. (Coolidge pointed out that, while it was in use, the rolodex might have sat on a female secretary’s desk.) Instead, we have to grapple with the messy work of human networks, with the expansiveness and power of, as Coolidge put it, “ideas that are almost fiction like in their magnitude.”