Joe Marston’s legacy runs deep. Craig Johnston called Marston his inspiration, and Tim Cahill in turn referred to the former Liverpool midfielder as his role-model.

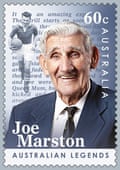

Since Marston’s sad passing on Sunday at the age of 89 – he was Australia’s oldest surviving national team player – the eulogies have been high in praise, albeit mostly modest in their size despite the breadth of his achievements.

Marston has been described as a “ground-breaker”, “pioneer” and the “grandfather of Australian football”. He was all these things and much more.

In most countries, Joe Marston would be a household name and a sporting icon. In Australia that level of veneration is mostly reserved for cricketers and Australian rules football players, and could simply never be attained by a footballer from that era.

Oddly enough, Marston himself would never have had it any other way. Those that met Marston – and I consider myself hugely fortunate to be among those – uniformly refer to him as a gentleman of great humility, one who took pride in an egalitarian nature. Visitors to the Marston home in Umina on the NSW central coast were greeted with copious amounts of teacake and genuine warmth.

Asked in an interview a few years ago how he would like to be remembered, Marston replied: “Oh, just as a fair player and an honest player.” That simple line spoke volumes.

Yet Marston’s achievements were truly remarkable and set the standard for decades to come. His move to England in 1950 pre-dated the current trend, yet his journey was as unlikely as it was ground-breaking.

Marston spent five hugely successful years at Preston North End as a central defender, helping the club win the Second Division, and then reach the 1954 FA Cup final, which his side lost 3-2 to West Bromwich Albion. No Socceroo repeated the latter achievement until Cahill exactly 50 years later, although Johnston famously scored in the 1986 final.

Marston ended his time in England with selection for the England League XI that faced their Scottish counterparts at Hampden Park. His room-mate in Glasgow was Manchester United’s Duncan Edwards, the bright young star of English football who was to be killed in the Munich air disaster a few years later.

A hugely popular figure for the club in the heart of defence, Marston finished his tenure at Deepdale serenaded to the tune of Waltzing Matilda played by the local brass band and backed by an admiring 30,000 crowd.

Marston was later named fourth on the list of the club’s top 100 players, a list headed by the legendary Tom Finney, from whom the Australian assumed the captain’s armband.

Marston won 37 caps during his 11-year national team career – a significant number in an era when Australia played few internationals. Marston is even considered by many to be Australia’s first homegrown coach, after being appointed to lead the team on and off the field in their home series against New Zealand in 1958. He is also one of only two Australian footballers, along with Johnny Warren, to be awarded an MBE.

Disappointments were few, though Marston was deemed ineligible to represent Australia in the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne due to his time as a professional in England.

Ted Smith, one of the younger members of the ‘56 generation, says coverage of Marston’s achievements at the time were scant at best, and that many local players would not have even been aware that Marston featured in the FA Cup final.

“Mainstream coverage of football [in Victoria] was minute at best, and Australian rules dominated everything,” said Smith. “I remember sitting through a couple of hours of newsreels just for a chance to see brief highlights of the FA Cup final run again.”

Growing up in Lilyfield in Sydney’s inner west, Marston started out with local club Leichhardt-Annandale and immediately made the transition to the senior team despite the presence of numerous internationals. He met life-long partner Edie in the club’s Lambert Park grandstand, which has since been rebuilt as a pavilion and named in his honour.

Marston’s life changed in the final days of the 1940s. His other passion was the surf, and in summer he could be found at Whale Beach on Sydney’s northern outskirts as a volunteer lifesaver. One weekend the call came through to the clubhouse that Marston had been offered a trial at Preston, based on the contacts and recommendation of a well-regarded English Leichhardt supporter. The apprenticeship at a local paint-brush manufacturer could wait. Within two months Marston found himself in postwar England playing football amid snow and slush. It was a world away in every sense.

Partly due to a warm welcome in Lancashire, and partly due to an honest work ethic – one that survived throughout his latter years – Marston made a success of his extraordinary opportunity.

His achievements were acknowledged in varying ways over the years. Most notably, the game recognises his contribution annually with the Joe Marston Medal for best player of the grand final.

A tiny and now dilapidated bar at Parramatta Stadium was also named in honour of Marston, but it pales in comparison to the grander edifices at the stadium named after local rugby league identities whose impact on their particular sport is not nearly as great. Such is football’s traditional status on the Australian sporting landscape.

“Josa” would undoubtedly be unbothered. Tall and upright with a firm handshake even throughout his latter years, Marston was rightly proud of his landmark achievements. But hubris and self-importance were not part of the Marston character. Simple family values and just being a good bloke were far more important.

“His inspiration and legacy was, and still is, tremendous,” says Smith. “And that is still being felt today and will continue long into the future.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion