This, I thought in disbelief, is really how I'm going to die.

It was the second Saturday in February, the first after the Super Bowl. I was supposed to be on a flight to New York. Instead, I was in a hospital bed in Scottsdale, Ariz., my eyes bloody from strain and sunken into my skull, lips chalky white and cracked, hands and feet swollen, skin peeling, tangled tubes snaking from my arm to a heart-rate monitor, a pouch of antibiotics and an IV bag suspended above my head. Jason Whitlock was yelling into my ear.

Two days before, Deadspin had published "The Big Book of Black Quarterbacks," a months-long project I had pitched and presided over, for which the staff and I had identified and profiled every African-American quarterback ever to play in the National Football League. In one section, I'd examined the media coverage of Washington Redskins quarterback Robert Griffin III, giving special attention to the criticisms lodged by Whitlock and then-ESPN talker Rob Parker. Parker had wondered aloud if RGIII was a "cornball brother," implying that he was somehow betraying blacks because he had a white fiancée and supposedly voted Republican.

Whitlock thought RGIII was betraying blacks, as well, only he came at the issue from the starboard side. In a series of columns appearing first on Fox Sports and then on ESPN, Whitlock had blamed the young quarterback's drab second-year performance on selfishness and a lack of humility. "RG III a victim of his own swagger," one headline had read. It was a kind of dog whistle, one that would obviously resonate a certain way with a certain segment of Whitlock's mostly white audience, and in our entry for RGIII I said as much.

Friday, gravely ill and exhausted from lack of sleep, I checked into the hospital. I had severe flu-like symptoms and had lost 10 pounds since landing in the desert. It was my third trip to the emergency room that week, but the doctors couldn't figure out what was wrong. A couple hours later, my phone rang. It was Whitlock. He'd read the piece.

Why didn't you at least call me before? he wanted to know. I told him I was sick, that I hadn't been well enough even to finish the project. Spoken aloud, the excuse sounded hollow, weak, even to my own ears. Then the paranoia hit him. Are you faking sick? Was this whole thing one long con to smear my name? Were your editors taking advantage of you, using you as a mouthpiece?

It just went on. How could I be so wrong about you, about your character? How could you be so wrong about mine? It was his job, he explained, to go against the grain. He couldn't understand how or why I had betrayed him. He thought we had big plans together.

I apologized over and over again for the better part of an hour, and then asked if I could call him back in a few days once I'd been discharged from the hospital. Reluctantly, he hung up.

I couldn't understand why Whitlock was so furious, so inconsolable. If anything, we'd gone easy on him, adducing his tired arguments in service of a broader point about the evolution of black sportswriting. The next morning, my phone rang. It was Whitlock again. Soon, he was reading me my own article, parsing, line by lonely line, exactly which phrases were mine and which were my editors'. I could tell he was offering me a way out. He just needed me to grovel, to beg his forgiveness, to massage his ego. But I was fucked up; I was all out of guilt. I finally told him the truth: I meant every word.

And that's how I fell out with Jason Whitlock, the most prominent black sportswriter in the country. It was a classic Whitlock encounter, hitting all the themes of betrayal that figure prominently not only in his life and work but in the many criticisms of both. Betrayal is what led to his defenestration from ESPN the last time around. Betrayal is why his best piece of writing never found the audience it deserved. And betrayal is at the heart of why the most prominent black sportswriter around is also the most hated sportswriter in the black community, and why, 10 months after Whitlock first announced his new endeavor, a black sports and culture site that he'll run under the aegis of his old enemy ESPN, the project is still struggling to get off the ground.

I spoke with dozens of his black colleagues over the past few months, and what struck me was how many of them outright referred to Whitlock as an "Uncle Tom," accusing him of attacking black culture generally and young black men and women specifically for personal profit and career advancement. Uncle Tom. The second-worst thing you could call a black man. How many times did I hear it? I stopped counting around 15.

"Look," one writer said to me. "I don't use the term Sambo lightly. But fuck Jason Whitlock."

You could hear Jason Whitlock smile.

"This is one of the greatest days of my life," he said. "Professionally, anyway."

It was Aug. 15, 2013, and Whitlock was a guest on the B.S. Report, Bill Simmons's podcast. This was a homecoming of sorts.

Seven years before, Whitlock, an ESPN personality at the time, had given an infamous interview in which, among other things, he napalmed colleague Scoop Jackson. ESPN fired him, and then the longtime Kansas City Star columnist got to work.

Bouncing around the internet like a loose grenade—first at AOL, then at Fox Sports—Whitlock put ESPNers like Rick Reilly, Rob Parker, Skip Bayless, Mark Schwarz, Stephen A. Smith, and many, many more to the torch. This was less a beat than a hobby, and no matter who was paying for his services, he made it his mission to harass Bristol. But now, somehow, he was back. And there was more.

"I met with John Skipper," he told Simmons. Skipper, president of ESPN, left headquarters and met Whitlock in Los Angeles, where the 47-year-old writer lives. The two broke bread, and then the president, often described as the most powerful man in American sports, gave his pitch.

"It was everything I'd wanted to hear," gushed Whitlock, who at the time of his departure from Fox Sports was developing his own show for the fledgling Fox Sports 1, called Red, White and Truth. "For lack of a better description—I hope this isn't offensive—but I'm going to get to do something along the lines of a black Grantland."

The idea, in theory, seemed natural. The network was extending its empire, monopolizing talent by launching new, semi-autonomous niche sites that would allow it to extend its coverage into new areas without diluting its core brand. First came Simmons's Grantland, the basic idea of which was to leverage Simmons's popularity to allow Bristol to lay claims on prestige longform writing and pop culture. Then, just a week before Whitlock's return, Nate Silver announced on the B.S. Report that he would be moving his own site, FiveThirtyEight, from The New York Times to ESPN, where he'd use data analysis to cover not just politics and sports, but science, economics, and more.

A third such brand, built like the others around a single strong personality and like them aimed at a specific but sizable niche audience, made sense. What Simmons had done for a certain sort of internet-native sportswriter, and Silver was doing for data journalism, Whitlock would do for black folks. This was big. But Simmons then pointed out one huge problem.

"This is something you and I have talked about a lot," Simmons said to Whitlock. "Where are the young, up-and-coming African-American sportswriters? Where are they?"

Ten months after that interview, the landscape in journalism has changed. John Skipper, it turns out, wasn't the only one who thought the Grantland model might be replicable. In October, investigative reporter and polemicist Glenn Greenwald announced that billionaire Pierre Omidyar would be staking a new project built around him. In November, The New York Times announced that it would essentially be replacing FiveThirtyEight with a new data-driven vertical—The Upshot, as it would come to be known—built around Pulitzer Prize winner David Leonhardt. In January, Ezra Klein of the Washington Post announced that he would be leaving the paper, and then did, taking a lot of its best young talent with him to found the website Vox.

The main similarity among all these projects is that they represent large companies investing in the journalist-as-brand. Another one, though, is that they don't look much like America. FiveThirtyEight and Vox both have been slammed for having overwhelmingly white, male mastheads, and The Upshot and The Intercept are similarly white and male.

Diversity in sports journalism, both print and online, is laughable and sad. In 2006, Scoop Jackson wrote an ESPN column in which he noted that there were four African-Americans among the 305 sports-desk editors in the membership of the Associated Press Sports Editors organization. Eight years later, the number is still only four. FiveThirtyEight, Vox, The Upshot, and The Intercept, meanwhile, show only one black staffer among their four mastheads, something that less reflects unique failings than those of the industry more broadly, Gawker Media included. The press, the world's watchdog industry, is also one of its most homogeneous.

This is the context within which Whitlock's new site was conceived. There have been sports websites built by and targeted toward blacks before, but none as well-funded as this, none with the freedom and possibility afforded by nigh-unlimited money. With his return to ESPN, Whitlock went from a columnist to a kingmaker.

Just as the head of Grantland handpicked his disciples, so would the head of black Grantland. Simply by existing, Whitlock's site would considerably bolster the ranks of of minorities writing on a national platform, and its founder would have the ability to select and mold the next generation of black reporters, editors, critics, and commentators. Last August, Skipper made Whitlock perhaps the most important African-American writer in the country, sports media's Black Pope.

The new year came, and then winter slowly stretched into spring, and one by one, these journalist-as-brand projects went live. But one website was missing: Whitlock's. After the Grantland and FiveThirtyEight launches, we now know how ESPN operates. First is the announcement, and then come the leaks, the press releases, the nuggets to remind everyone of the site. But since Whitlock's proclamation last August, there has been no further word from ESPN on a black Grantland, and the rumor mill was surprisingly quiet.

Whitlock wouldn't talk to me, so I called Rob King, ESPN's senior vice president of SportsCenter and news. He's the highest-ranking African-American in the company; I figured he would know if there'd been any progress. But when I asked him about black Grantland in mid-April, he said he had no news to give.

"I can't really talk to you too much about the project," he told me, "because to be perfectly candid with you, it isn't far enough along for me to speak substantially about it."

Despite the demurral, work on the site is ongoing. The site doesn't yet have a name. "Soul Food" was one candidate, according to an ESPN source. Another was "Sons of Sam," a reference not to the serial killer but to the pioneering black sportswriter Sam Lacy. (An ESPN spokesman told me today that both names are out of the running.) It will be a bicoastal operation like Simmons's site, with around a dozen people in Los Angeles, a couple working from New York, and a minder or two back in Bristol. Organizationally, however, it will not be a close sibling of Grantland, which along with FiveThirtyEight now lives under the umbrella of ESPN's new Exit 31 unit. A better comparison might be the Worldwide Leader's site for women, espnW, whose bleak example was cited by Elena Bergeron, ex-ESPN The Magazine reporter and the first editor-in-chief of Complex's basketball blog, Triangle Offense. Despite a talented lineup and the support of a number of corporate sponsors, espnW is less a pipeline of women's-interest fare to ESPN.com than a sort of ladies auxiliary, garrisoned off from ESPN's main body of work. Few espnW stories get front-page promotion, and Bergeron wondered if black Grantland was in for similar neglect. "Are you bastardizing the people who are writing about minorities and women by putting them on their own site?" she asked.

Mockups of the page have been passed around. One source explained that when you open the site, hip-hop music plays in the background, like the homepage of a multi-level nightclub or an old Myspace profile, stopping and starting when you click on different links and so forth.

We were told last month that Whitlock had almost signed an editor to manage the day-to-day goings on at the site. Recently, though, this cryptic ad for an "Executive Editor Special Project" popped up on ESPN's careers page. (It was originally titled "Executive Editor Whitlock.")

There is no staff to speak of, though I know that Whitlock has approached a diverse array of writers and editors for various positions on the site. Some names I've heard: Ayesha Siddiqi, late of BuzzFeed; former Deadspinner Emma Carmichael; former Gawker writer Cord Jefferson; former ESPN The Magazine editors Jenn Holmes and Ashley Williams; Vince Thomas and Khalid Salaam, formerly of The Shadow League, a black sports site founded with seed money from ESPN and now affiliated with Black Enterprise; and, remarkably, Ta-Nehisi Coates, one of the country's most perceptive writers, particularly on the subject of race.

None of those people has signed on, at least not yet. The names, though, might offer a clue as to what Whitlock's up to. These are mainly young journalists, both black and white—not a hot-taker among them. It seems that Jason Whitlock's ideal site is one in which nobody writes like Jason Whitlock.

Born in Indianapolis in 1967, Jason Whitlock was raised in the city's suburbs. He was a big kid before he was a large man, and in his household, fried food was a staple. Though he was both tall and wide, he was a nervous boy, so paranoid that at 10 years old, he would sit on the couch, plopped in front of the television, knife in hand until his big brother got home from school. It's a trait that has stuck with him for the rest of his life.

"Jason was always kind of scared of everything," Whitlock's mother, Joyce, would tell The University Daily Kansan in 2001.

Whitlock gravitated to youth football. In high school, he won all-state honors playing on Warren Central High School's varsity offensive line, blocking for his friend, future NFL quarterback Jeff George. He was good enough to win a football scholarship to Ball State University in Muncie, about an hour and a half from home.

Whitlock playing college ball. Video via Ball State University.

Twenty-five years later, Whitlock still makes it a point to tell people he played D-I ball, but he spent most games riding pine, and soon, his NFL ambitions began to fade. In 1989, his fifth year in school, he walked into the Ball State Daily News's office. He wanted to try sportswriting.

Whitlock had grown up reading the sports section of the Indianapolis Star, and also idolized the legendary Chicago-based columnist Mike Royko, a raconteur and irascible contrarian whose life and career were a series of fights, largely of his own picking. From the start, Whitlock used his hero's career as a benchmark; he wanted to be sportswriting's Mike Royko.

Whitlock wasn't a natural writer, but he worked hard, and had strong convictions about what sportswriting was and should be from the moment he walked in the door. As The Pitch chronicled in 2004, from the start, he hated how gentle Midwestern writers acted more as cheerleaders than critics, and thought columnists should be harder on their local teams. He also bucked against their refusal to use the first person, their pretense that they were coming at stories from some objective, omniscient perspective. When he graduated in 1990, he began a part-time fellowship at the Herald-Times in Bloomington, Ind., making $5 an hour.

Sportswriters often romantically compare their career arcs to those of athletes. Though Whitlock was just in the minor leagues and still a poor writer, he quickly showed he was a unique talent. Just a couple of years removed from Division-I football, he not only grasped the game's complexities, but also understood the lifestyle and mentality of the contemporary athlete. Whitlock was also black, a rarity in journalism in itself. At the Herald-Times, Whitlock often wrote alongside famed sportswriter Bob Hammel, and happily played the conservative foil to Hammel's liberal. But the young writer wasn't conservative so much as he was a willing, eager fighter who understood that to stand out, he had to be different.

Most important, though, was Whitlock's dedication to writing. He would stay in the office deep into the night, writing, revising, reading back issues of the newspaper to study James Kilpatrick's syndicated Sunday column, "A Writer's Art." (This was in the "beloved uncle" phase of Kilpatrick's career, in Garrett Epps's phrase. During the Civil Rights era, however, Kilpatrick was an architect of the hard-line segregationist strategy of "massive resistance.")

Whitlock soon moved on, working as a reporter first in Rock Hill, S.C. and then in Ann Arbor, Mich., where he made a name "starting all that trouble," he'd later boast, while writing about the Fab Five and Michigan football. In 1994, the Kansas City Star, then as now one of the best sports desks in the country and a breeding ground for future national writers, hired him as a full-time columnist for $60,000 a year. People work their whole lives to get their own column, and Whitlock, a 26-year-old black guy, had his own at a major paper four years after graduating. This sort of thing didn't happen.

Whether Whitlock knew it or not, the column would be a heavy burden. There are few black journalists working at major publications, and even fewer who get the chance to write columns from their own perspective, to earn a living dispensing opinion. The lucky ones who do are tasked with representing their entire race. It's a nasty paradox. Blacks aren't any more monolithic than any other group, and there's no such thing as a singular "black point of view." But because there are so few blacks writing, whichever black point of view is presented is often taken as broadly representative and whoever pens it enjoys an air of inflated authority when talking about African-Americans or racism, with little pushback from the very few minority writers or from white audiences.

Whitlock quickly found a niche at the Star writing about the intersection of race and sports. After just six months, then-editor Mark Zieman had to rip up his contract and offer him a new, $100,000 deal to keep other editors from poaching his young star.

One reason the columnist was such a draw was because he was an African-American with a sense for the theatrical, working in a marquee spot for a majority-white audience. Twenty years later, Washington Post columnist Clinton Yates described it to me simply: "White people want to be entertained by black men."

Whitlock reveled in the spotlight. Early in his time at the Star, still new to the city, he wrote an article eviscerating the Kansas City Chiefs. Many writers wouldn't even show up to the park after writing something like that, but Whitlock seemed almost to be searching for confrontation. The day the column ran, he stood in the middle of the Chiefs locker room, broad-shouldered, waiting for a player to approach him.

He approached his 800 words with monkish dedication, and the column became his entire world, his raison d'être. In 1996, the Star hired another young writer, Joe Posnanski. Though they were the same age, Posnanski was Whitlock's opposite. Joe was white; Jason was black. Joe loved baseball; Jason loved football. Joe wrote with a soft touch; Jason wrote with a sledgehammer. As Candace Buckner—currently one of the few black women covering an NBA team, and formerly a colleague of theirs at the Star—put it: "Joe Posnanski was the storyteller. Whitlock was the provocateur." The two soon formed one of the best one-two punches in the country.

In 1997, black journalist and author Ralph Wiley took notice.

Wiley was brilliant. He wrote or co-wrote 10 books, and was renowned both for his magazine features, which elevated the form to an art, and for his columns, written in rhythmic, almost singsong prose, often addressed to a ghostly third party whom readers never knew or met. But Wiley's significance extended beyond his writing. Along with Washington Post columnist Michael Wilbon, he was one of the the two most revered black sportswriters in the country. The source of their influence was simple: They actively sought out and mentored up-and-coming African-American writers. They showed younger blacks, isolated in newsrooms throughout the country, that they weren't alone.

As he did with so many others, Wiley took Whitlock under his wing. The two were fast friends. Wiley mentored him, taking time to talk with him, read over his drafts, critique his columns, massage his ego, ease his fears, and, when necessary, call him on his bullshit. Whitlock and Wiley weren't at all similar—Whitlock was a slugger while Wiley danced through his columns, and though neither flinched from talking about race, their opinions rarely overlapped. Still, Whitlock consciously modeled his writing after his hero's, and even tried a few times to wink at that mysterious third party, just over the reader's shoulder.

In 2000, ESPN launched Page 2, a sort of proto-blog that reflected much of the mordant, smart-ass sensibility now associated with sites like Grantland and Deadspin. Initially, Wiley and Hunter S. Thompson anchored the site; the following year, they were joined by Pulitzer-winner David Halberstam. In 2001, ESPN also brought on Bill Simmons, one of the most widely read sports bloggers in the country.

Whether he was an innovator or a popularizer is up for debate—Sports Illustrated's Curry Kirkpatrick was doing the sports-as-pop-culture thing long before Simmons first sat down to watch Teen Wolf—but there's no question that the Sports Guy changed the dynamic. He got to Page 2 by making his name as a superfan, an everyman who broke into journalism by having the gall to write about sports with humor and joy, and his style became the default across the sports internet. No one was more influential.

In Kansas City, meanwhile, Whitlock had turned into a bona fide celebrity. He was getting recognized on the street. He'd parlayed his column into a morning drive-time radio show. He'd taken to calling himself "Big Sexy"—and, most telling, the nickname actually stuck.

"There are few writers who own a town," Denver Post writer Woody Paige told The Pitch. "Royko owned Chicago; Jim Murray, Los Angeles; Mitch Albom, Detroit. Jason, it seems, has developed an incredible following in Kansas City."

It was time to go national. In 2002, a year after hiring Simmons, ESPN offered Whitlock a slot on Page 2. He accepted, and put in his work while continuing to churn out columns at the Star.

This put him in a special position. Running alongside Simmons, he was implicitly introduced to the country as one of the stars of a rising generation. (In addition to Page 2, he often appeared on television, on ESPN's The Sports Reporters, as the house younger guy.) But he was also being placed alongside Wiley, Halberstam, and Thompson, writers with intellectual heft, writers whose opinions mattered.

And then the legends started dying. First was Wiley, who had a heart attack in 2004; Thompson took his own life the following year. (Halberstam, who left Page 2 after a year, would die in a car accident in 2007.)

Wiley's death shook the community of black writers; it was only after he'd died that people learned just how many young minorities' lives he had touched. Whitlock was heartbroken.

And then he got angry. In March 2005, ESPN tapped Scoop Jackson to fill Wiley's spot. Whitlock thought that Jackson, four years his senior, was a poor writer and a lazy thinker. But Jackson was an important figure if for no other reason than that for years he was the de facto face of Slam magazine. He was popular because he wrote and endeared himself to a specific demographic of young, city-dwelling, basketball-loving black men. He was decidedly and, some thought, measuredly "urban," and though Whitlock still listened to rap and maintained a friendship with Kansas City-based rapper Tech N9ne, he had slowly over the course of his adulthood evolved into hating what he called "hip-hop culture," which included rap music itself, the worship of rap artists as pop idols, the genre's casual misogyny, the ubiquitous use of the word "nigga" in songs—not to mention the people he saw as pandering to the lower impulses of hip hop's audience.

Scoop represented everything Whitlock had come to identify as the undoing of black America, and now here he was, sitting in Wiley's chair. Could ESPN really not see the difference between Wiley and Scoop?

A year into his Page 2 gig, Scoop published a column titled "What I've Learned in Year 1..." It ended like this:

[A]lthough his son Cole is carrying the weight and the torch, I am carrying Ralph Wiley's legacy with every word I write. And I just hope I'm doing him justice.

This was too much for Whitlock, who thought himself a more worthy heir to Wiley's mantle. He decided the onus was on him to call Jackson out.

"It pissed me off that the dude tried to call himself the next Ralph Wiley and stated some [bleep] about carrying Ralph's legacy," Whitlock told The Big Lead in September 2006. "Ralph was one of my best friends. I hate to go all Lloyd Bentsen, but Scoop Jackson is no Ralph Wiley."

Though Whitlock was never a great wordsmith, he always knew how to throw bombs. That was his strength. Over the years he earned a reputation, and a lot of attention, as a serial feuder who would hop capriciously from beef to beef with other media personalities around the country—everyone from Charlie Pierce to Deadspin's editors to ESPN's Keith Clinkscales to Mike Lupica to Joe Posnanski. Even today, no one really knows why Whitlock does this. Maybe he just gets bored; maybe, as someone close to him suggested to me, it's his paranoia—the belief that colleagues are forever trying to undermine him, to betray him; maybe he just knows that people like to watch him fight. (He can also be generous with his colleagues. Bomani Jones, one of ESPN's brightest bulbs, called Whitlock a great champion of his work. He added: "Anyone who has a blanket negative view of Jason Whitlock doesn't know him well.")

In any case, Whitlock lit up his ESPN colleague in an interview with The Big Lead. He said Jackson's writing was "fake ghetto posturing … an insult to black intelligence." He said Jackson was "bojangling for dollars." He all but called him an Uncle Tom.

Whitlock was summoning all sorts of ugliness, striking many of the same sour notes that his own detractors would hit a few years later. Black men in America are often depicted in a very specific way, as inarticulate, unread, impulsive, violent, and altogether unrefined. When blacks show traits that run counter to this depiction, they're often seen—by whites and blacks alike—as somehow faking it, ashamed of their blackness, or else removed from black culture.

One's perceived "blackness," then, generally runs parallel to how recently removed they appear to be from a violent, impoverished life. It's a false stereotype, but one that many, like corrections officer-cum-rapper Rick Ross and ESPN personality Stuart Scott, consciously play to in various ways with their tone, vocabulary, and mannerisms. Jackson, Whitlock thought, was exaggerating his connection to the hood.

Maybe Jackson's writing was a kind of public performance, but so, unquestionably, was Whitlock's interview. He was appointing himself high priest of blackness with his charge that Jackson was "bojangling for dollars." This wasn't even a dog whistle; it was a direct callback to a time when black men were jesters who literally danced for white folks' scraps. Whitlock surely knew what he was doing. He could have said any of this privately to Jackson, and that would've been that. But words and context matter. Going public in front of audience principally made up of white men, Whitlock may as well have been standing in a crowd, pointing and saying, "Look at this nigger here."

ESPN fired Whitlock soon after. And then his career exploded.

When I heard Whitlock announce his site on the B.S. Report, I was already packing my bags. This was my chance, I thought, even though all I knew about Whitlock at that point was that he was a popular black sportswriter. As a college jock, I was a latecomer to journalism, not seriously considering it as a profession until my junior year of college. I decided I wanted to write magazine features, and then decided I wasn't good enough. So in the fall of 2010, I enrolled in graduate school at New York University and walked out a year and a half later with a master's degree, a student-loan debt in the six figures, and a job making about $400 a week writing 5,000-word cover stories at a ridiculously good, ridiculously understaffed alt-weekly in Dallas.

After six months I transferred to the Village Voice, its sister paper in Manhattan, where I worked for seven more months before parting ways.

I think about this now when I think about Bill Simmons's question to Whitlock. Where are all the young black writers, he'd wondered. Woodshedding, like anyone else. That's how it was for me. That's how it was for Joel D. Anderson, who'd spent over a decade grinding away at newspapers in Houston, Shreveport, Dallas, Oklahoma City, and Atlanta before being hired by BuzzFeed's since-scaled-back sports vertical. For others, writing was an avocation, to be done on the side when the bill-paying work was finished. Ayesha Siddiqi, whom Whitlock recently tried to hire to run his site, was a Twitter personality with little writing experience. (She had taken a job at BuzzFeed as editor of their "Ideas" vertical in January, and since she didn't follow sports, she felt unqualified to accept his offer.) When I called Eddie Maisonet, the founder and editor of The Sports Fan Journal, he was squatting in an unused conference room on Google's campus in Mountain View, Ca., where he works on the Google Places team, and blogs during lunch and on the company shuttle to and from work.

These are the realities of being a young writer. But in his interview with Simmons, Whitlock seemed blind to them. "Some of those opportunities are limited for African-Americans," he said, "or they limit themselves."

It was classic Whitlock, placing structural barriers on the same plane as the personal failings of young black people. Whatever he thought he was saying, what younger writers heard was, They don't want it enough. When I talked to Anderson, he pointed out this quote specifically.

Whitlock knew me from Deadspin, for which I began freelancing in February 2013. He met some of the Deadspin staff in August of that year and mentioned something about wanting to meet me, but I'd already left New York and moved home. Soon after, I sent him an email introducing myself. We spoke on the phone a couple times. In late October, broke and considering a new career, I sent Whitlock a résumé and some clips, thus beginning a decidedly unconventional vetting process.

Whitlock seemed to be trying to take the measure of my blackness. I'd grown up firmly middle class in a three-story house on a half acre with two parents, two siblings, two dogs, and two cats. Whitlock was impressed to learn that I hadn't set foot inside a private or majority-white school until college, and that, yes, I had black friends. When he asked me about my favorite writers, I named David Foster Wallace and Ta-Nehisi Coates. When he asked me about my favorite sportswriters, I told him Whitlock. We got along just fine.

Honestly, though, I didn't know anything about Jason Whitlock. I'd never read his columns, and I'd rarely spoken to anyone who had. In our conversations, he didn't divulge much of anything about himself. Instead, he spent his time laying out a vision for me and for his site that was too good to pass up. I could write at length about whatever I wanted. I pitched him shit that I'd figured would be deemed outlandish, stories that would require things like access, air travel, hotel rooms, months of reporting, piles of someone else's money, and Whitlock said of course. He then asked me if I was fine leaving Deadspin and writing for a "black website," and I said of course. Just in case, he assured me my best work would get on ESPN's front page. He liked that I had no interest in television, and that at my core, I thought of myself as a writer, but he told me I'd be invited on Outside The Lines anyway. I'd been broke for every single second of my adult life; Whitlock had Disney money. The whole thing felt like a joke, but he was serious. And if that wasn't enough, Whitlock struck me in our conversations as a generous, genuine, genuinely decent guy who didn't really know me, but already trusted me more than nearly anyone else I'd worked with. I decided I liked him right back.

By the new year, I was fully ready to sign on once the site had become official. He kept me updated with his meetings with the top brass in Bristol, and told me I was his "number-one pick" (a compliment I now know he lavished on at least one other recruit).

He just had to settle on a managing editor who'd actually run the site day to day. The plan was for ESPN to make its first black Grantland announcement at NBA All-Star weekend in mid-February. The site would be fully staffed by April, and it would launch in August, just in time for NFL preseason.

We lived on opposite coasts and never shook on it, but I was ready. There would be interviews, of course, but he told me I was in unless he found out I was a "mass murderer or something." I laughed and told him I hadn't killed anyone yet.

We texted or spoke every couple of weeks. I gave Whitlock recommendations for hires. I was looking into buying a car, bookmarking Los Angeles apartment ads. Though we were never friends and though we'd never even met, Whitlock and I had seduced each other. I can see now that he saw something of himself in me. I figure he saw me as one of the good ones—someone who was talented and, who, like him, really wanted this.

And then, in January, Deadspin offered me a full-time job; I'd so completely given up on the idea of working full-time at Gawker Media that the offer actually shocked me. They wanted me to start Feb. 1. I immediately called Whitlock. He told me he'd understand if I took the position temporarily. Formal interviews, he said, were supposed to start soon, but they were lagging behind, and he knew I needed the security that came with a full-time salary. I felt squeamish about taking a position with one foot already out the door, so he offered to help me out in the interim if I turned Deadspin down.

In the end, I decided to sign on at Deadspin. They were offering a salary, benefits, and a chance to return to New York, while Whitlock's site had yet to materialize. Anything could happen, I thought. Whitlock could get hit by a car tomorrow, or else find someone he likes better. Also, it was harder than I thought to leave Deadspin's large, diverse readership for the unknown waters of a black startup. I accepted the offer, then flew out to Arizona for one last weeklong vacation before giving up all the freedom that came with being an underemployed freelancer.

Then I got sick—a severe allergic reaction, it turned out, to the medicine that I'd been given to treat a staph infection. We published "The Big Book of Black Quarterbacks," and soon enough I was in a hospital wasting away while Jason Whitlock screamed at me about my lack of character.

Though I didn't know it then, that would be the last I heard from Whitlock. He was on a mission to save black sportswriting, and after some time had passed, I realized that he intended to do it without me.

In April 2007, Jason Whitlock made it to a stage even ESPN couldn't match. He was a guest on two episodes of The Oprah Winfrey Show, just days after writing the column that had turned him into a household name.

On April 4, cranky old radio personality Don Imus had taken up the subject of the previous night's NCAA women's championship basketball game between Tennessee and Rutgers. He called the Rutgers team some "rough girls." His executive producer, Bernard McGuirk, called them "some hardcore hoes." Imus laughed.

"Those are some nappy-headed hoes, right there," he said.

The country flipped out. Blacks and women called for Imus to be suspended, and he eventually was. He also gave a half-apology, with the caveat that his comments were somehow a result of black culture.

"I know that that phrase [nappy-headed ho] didn't originate in the white community," he started. "That phrase originated in the black community. I'm not stupid. I may be a white man, but I know that these young women, and these young black women all through that society are demeaned and disparaged and disrespected by their own black men, and they are called that name."

Columnists lined up to write about the imbroglio, the signal difficulty being that there's really only so much to say about a white man calling young black women "nappy-headed hoes." Whitlock—now writing for AOL and the Star—managed to find a unique angle. It was a tour de force of shit-stirring.

Thank you, Don Imus. You extended Black History Month to April, and we can once again wallow in victimhood, protest like it's 1965 and delude ourselves into believing that fixing your hatred is more necessary than eradicating our self-hatred.

While we're fixated on a bad joke cracked by an irrelevant, bad shock jock, I'm sure at least one of the marvelous young women on the Rutgers basketball team is somewhere snapping her fingers to the beat of 50 Cent's or Snoop Dogg's latest ode glorifying nappy-headed pimps and hos.

I ain't saying Jesse, Al and Vivian are gold-diggas, but they don't have the heart to mount a legitimate campaign against the real black-folk killas.

It is us. At this time, we are our own worst enemies. We have allowed our youths to buy into a culture (hip-hop) that has been perverted, corrupted and overtaken by prison culture. The music, attitude and behavior expressed in this culture is anti-black, anti-education, demeaning, self-destructive, pro-drug dealing and violent.

Where most writers were railing against Imus's open expressions of racism and sexism, and some were drawing a line between an irrelevant shock jock feeling free to use these kind of words and a culture of white supremacy, Whitlock saw the opportunity to separate himself. He didn't exactly defend Imus so much as write him out of the scandal, instead chastising blacks for "wallowing in victimhood." In just under 800 words, Whitlock found a way to berate 50 Cent, Snoop Dogg, Kanye West, Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, Rutgers head coach Vivian Stringer, hip hop, athletes who listen to hip hop, prison culture, black self-hatred, Dave Chappelle, BET, MTV, black-owned radio stations, crack cocaine, black-on-black crime, absent fathers, and black school bullies.

It was a hit. Television producers flocked to Whitlock. He went on air with cartoonish conservative pundit Tucker Carlson to explain that the real problem here was black people:

We keep deluding ourselves and getting caught up in distractions that have nothing at all to do with what's really holding black people back, and it's our own self-hatred.

Don Imus is irrelevant to what's going on with black people. Don Imus is no threat to us. Don Imus will not shoot one of us in the street, he will not impregnate our daughter or our sister and abandon that kid and that woman.

Whitlock continued on, chiding Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson for refusing to accept Imus's apology. This was fair enough, even though chiding the two had long ago become an empty ritual, a way of signalling one's "seriousness" about racial issues in the whiter, starchier precincts of the media. But then, later in the interview, he referred to them as terrorists.

"That's a very brave point of you to make," Carlson said, "particularly right now when almost nobody is saying that out loud."

Whitlock then hopped on The Oprah Winfrey Show, where he railed against hip-hop culture before an audience of six million whites. "We've allowed our children to adopt a hip-hop culture that's been perverted and corrupted by prison values," he declared. "They are defining our women in pop culture as bitches and hoes. … We are defining ourselves. Then, we get upset and want to hold Don Imus to a higher standard than we hold ourselves to. That is unacceptable."

Whitlock was paraded around the major networks; along with Oprah, he appeared on The Today Show and agreed to a sparring match on CNN with Al Sharpton, the whole while saying that the problem wasn't Imus, that black people were the reason white people were being racist.

Carlson called Whitlock brave, and it was a compliment that aligned with how Whitlock saw and sees himself. In truth, it was the opposite. Whitlock, in the name of "telling it like it is," was merely flattering the prerogatives of white people who preferred that any discussion of race begin with the pathologies of black people and their culture, not with the de jure and de facto system of oppression in America and its residue. Whitlock was chickenshit. He took the easy way out. He did what comes easiest to an American, even in the 21st century, even—especially—now in the age of Obama, himself no stranger to this sort of ahistorical rhetoric. He blamed the black folks.

It may not have been a cynical performance along the lines of the ones David Webb and Dinesh D'Souza give today when minorities dare to air racial grievances, but for white reactionaries Whitlock was offering the same sort of shallow expiation. He was the ever-valuable black friend, the Acceptable Negro.

Just days after turning up on Oprah, Whitlock again wrote cultural conservatives into orgasmics, penning another column in which he warned parents of the looming danger of pop culture as a whole. In July, Whitlock appeared on an episode of the The O'Reilly Factor talking about Michael Vick's dogfighting ring.

"It has made destructive behavior normal," Whitlock said, blaming Vick's torture and murder of dogs on hip hop. "This hip-hop culture is destructive to young people, and if you want to stay in that culture, it will lead you to a coffin, a jail cell or major embarrassment."

That was the year Whitlock became a phenomenon. He'd endeared himself to a certain kind of reader as black culture's starkest critic. He was the racist right's unwitting attack dog, here to explain how black people were the problem. He became a bona fide, nationwide cash cow, even as his credibility as a writer and a thinker was beginning to crumble.

The problem wasn't really that Whitlock was preaching social conservativism or criticizing blacks. His views weren't so far removed from W.E.B. Du Bois's "Talented Tenth" theory or even the Nation of Islam's "Do for self" tenet, and they lined up neatly with those of Bill Cosby, or The Boondocks's Uncle Ruckus, or your own uncle, sparring across the table with you at Thanksgiving dinner. They weren't all that crazy.

The difference between Whitlock and your uncle sitting next to you at Thanksgiving dinner, though, is that your uncle doesn't influence shit. He doesn't have so much as a megaphone to voice his opinions, let alone a website with national reach. And more important, your uncle isn't belting out his antiquated, inaccurate beliefs to a mostly white, mostly male audience of millions.

He isn't hanging out with Bill O'Reilly, talking about how records—not the legacy of slavery and terrorism and redlining, but pop records—are the real issue. He isn't getting patted on the head by Tucker Carlson for being brave enough to say that the problem with black people is black people. If he were, though, and if he were saying these things for the sake of going against the grain, he would be hurting the very same people to whom he claimed to be doling out some well-meaning tough love.

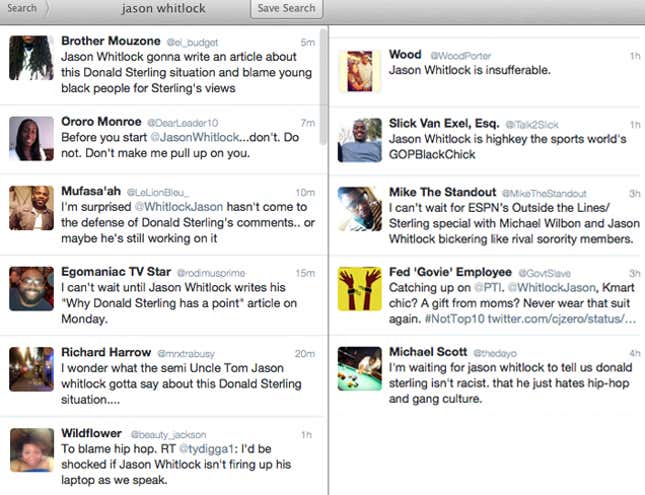

While Whitlock has lashed out at everyone over the years, his greatest hits have all had something in common: They involve him criticizing some combination of women, young black men, and black culture. There was the Serena Williams is fat column. There was the let's all leer at Erin Andrews and Elisabeth Hasselbeck "catfighting" column. There was the Serena Williams crip walked at Wimbledon because black people don't demand she act better column. There was the Jay-Z shouldn't be a sports agent because he is a rapper who says "nigga" column. There was the Lolo Jones needs to stop crying when she loses at the Olympics column. There was the Robert Griffin III needs a lesson in humility column. It's so routine that when Donald Sterling was caught on tape talking about how he didn't want his mistress bringing black people to Los Angeles Clippers games, blacks took to Twitter to speculate on just how Whitlock was going to use this opportunity to explain that black people are the problem.

They weren't even wrong. When Whitlock weighed in on Sterling, the piece was strong in places, and—perhaps because it came out not hours but days after the news broke—uncharacteristically measured. Whitlock was dead-on when he wrote this:

Sterling adheres to a pervasive culture, the hierarchy established by global white supremacy.

"I don't want to change the culture because I can't," Sterling says. "It's too big."

This was Sterling's one moment of clarity. The culture of white supremacy created Donald Sterling. He did not create the culture.

Even here, though, Whitlock couldn't help but explain how the real issue here was black pathology:

He is adhering to the standards of his peer group. He is adhering to the standards of the world he lives in. It's a world inhabited by all of us. It's a culture that shapes everyone's worldview on some level. It fuels the black self-hatred at the core of commercialized hip hop culture, and is at the root of the NAACP's initial plan to twice honor an unrepentant bigot with a lifetime achievement award.

Whitlock was writing about an evil and indefensible man—not some unfortunate nobody caught in a moment of oafish racism, but a powerful real estate baron expressing the logic of the plantation, of segregation, of redlining. These were beliefs Sterling had apparently acted on before, as a landlord who, as two multimillion-dollar housing discrimination lawsuits alleged, refused to rent to blacks and Latinos. And yet, in the midst of making a point about structural racism, Whitlock somehow found a way to bring the issue back to the depredations of hip-hop culture, of how hip hop is destroying blacks.

The problem with all this, of course, is that hip hop isn't destroying blacks any more than Hank Williams's songs about boozing and womanizing destroyed white people. An article on The Wire, published earlier this year, showed that as hip-hop music became more popular, more mainstream, overall and violent crime rates both dropped.

But who cares about evidence when there is a false equivalence to strike? On the one hand, he wrote, in effect, Donald Sterling looks at black men as cattle, as his personal property who can play for him and earn money for him, but who aren't worthy of coming to his games or living in his apartments. On the other, black self-hatred is why people curse and use misogyny in rap, and black self-hatred is why the NAACP took bribes from Sterling.

The two have nothing to do with one another. Blacks didn't enable Sterling, just like blacks didn't enable Imus. Still, when the devil himself was caught on tape, Whitlock looked at blacks and said, Something has to change.

There are two distinct readings of the history of blacks in America.

The first describes the United States of America as a nation that by design practices and profits from racial inequality. It traces the continuity between slavery and Jim Crow, and Jim Crow and redlining, and redlining and the drug war, and so sees a direct line between the original sin of slavery and the present condition of our worst-off black neighborhoods. It doesn't argue that the individual isn't responsible for the consequences of his actions, but rather that at the population level, black Americans are the victims of systemic racism—conscious public policy that has made black communities and institutions weaker and more vulnerable than those of other groups, and has so set black Americans up for failure. It recognizes that the history of blacks in this country is not a tangent from or parallel to the history of the United States, but the very reason why America is America.

The second locates the differences between blacks and other groups not in ongoing political violence, but in a unique black pathology. This is the ideology of the respectable center in American politics, offered in various guises by figures as different as Paul Ryan …

We have got this tailspin of culture, in our inner cities in particular, of men not working and just generations of men not even thinking about working or learning the value and the culture of work, and so there is a real culture problem here that has to be dealt with.

… and Barack Obama:

If Cousin Pookie would vote, if Uncle Jethro would get off the couch and stop watching SportsCenter and go register some folks and go to the polls, we might have a different kind of politics.

This was essentially what Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jonathan Chait were wrestling over in their recent debate, with Chait siding with Ryan and Obama in claiming that the "cultural residue" of hundreds of years of oppression has become a self-sustaining and distinct impediment to black success for which black Americans need to take responsibility, and Coates more convincingly claiming that American democracy was and is designed to exclude blacks from the main line of public life.

Whitlock, unsurprisingly, sided with Chait, even bringing him on to his podcast to talk Michigan football.

He particularly enjoyed when Chait analogized black history and ongoing systemic racism to a basketball game, and then advised blacks how to deal:

A person worries about the things that he can control. If I'm watching a basketball game in which the officials are systematically favoring one team over another (let's call them Team A and Team Duke) as an analyst, the officiating bias may be my central concern. But if I'm coaching Team A, I'd tell my players to ignore the biased officiating. Indeed, I'd be concerned the bias would either discourage them or make them lash out, and would urge them to overcome it. That's not the same as denying bias. It's a sensible practice of encouraging people to concentrate on the things they can control.

This is a trivializing and worthless metaphor, and it commits the fundamental error of positioning the beneficiaries of systemic injustice (Team Duke) as distinct from its enforcers (the refs). But even on its own terms it falls apart. Chait was saying that the members of Team A—faced with referees who are knowingly, purposely cheating them out of a fair shot to succeed, and in this case for something as arbitrary and as capricious as the idea of race—should play on valiantly. Instead of despairing, or refusing to play altogether, Team A's players should keep their heads down, work hard, and play by a set of rules designed specifically to deny their team victory, hoping that a player or two will manage to fluke a double-double. Chait was underestimating and, more importantly, discounting the sheer amount of rage that Team A would experience every day and would have every right to experience. He was telling Team A's players to just get on with this sham, to ignore how fucked they are, how it's in the officials' interest to keep fucking them, and how this is why Team A will remain fucked as long as it agrees to play this game. In the face of blatant injustice, he was telling Team A to pretend it didn't exist.

It was fascinating to watch Chait stumble along blindly through his own fog of good intentions and unexamined privilege—proof that even among our most hardened liberal champions and leading political writers, white privilege endures. Team A's actions in this metaphor are the very definition of black respectability politics.

Many dismissed Chait after this, but Whitlock emerged as more or less the only prominent person who thought Chait had the better of the debate, because Chait was articulating Whitlock's fundamental beliefs.

On his podcast, Whitlock praised the writer, telling him, "the analogy you gave was beautiful."

Whitlock believes in the black version of the American dream, that if only African-Americans would just pull themselves up by their bootstraps, educate themselves, and work hard, there would be equality in this country—that if only blacks were better, more worthy, their democracy would include them.

Respectability politics and claims about black pathology are at best well-intentioned racism, and bullshit besides. They're the basis of Whitlock's view of race relations, though, and they explain his sense of mission and self-appointed position as moral arbiter. He wants to change blacks, to civilize them, to save them from themselves.

The single most prominent black sportswriter in the country, then, is not only engaged in a campaign of denigration against African-Americans, but in a rewriting of knowable—and known—history. Every time he blames Jay Z for issues more properly attributed to governmental policies of housing discrimination, every time he claims that young black men using the word "nigga" are the functional equivalent of a mass campaign of ethnic cleansing, every time he treats alleged self-hatred as more consequential than a political system whose essence is the denial of equal opportunity, he is distorting the truth.

This isn't just a moral failure; it's a journalistic one. And when you look back over his past, it appears that one reason he's gotten away with it is that the writer who rose so quickly was answering to no one, all along.

"I don't think Jason Whitlock has ever had an editor who has ever pushed back and said, 'You can't say this, or you shouldn't say this,'" said one ESPNer.

A source inside Fox Sports went even further: "He was working with guys named Matt and Kyle and Bryan! The people at Fox Sports needed to edit him better, but no way people were going to touch his shit."

This is the source of the most severe charge leveled at Whitlock by his black colleagues: that he's an Uncle Tom—a black person who, by the strictest definition, wilfully takes damaging action against other African-Americans for personal gain and/or the approval of whites.

"I mean, I respect his hustle, I guess," one writer said, grudgingly. "But he's an Uncle Tom. The reason he's a notable writer is because of his ability to stir up things. He always talks about black apology."

"It's hard," another admitted, "to see him as anything but a race traitor."

I tend to subscribe to a different theory on Whitlock. What people see as his self-serving imposture is in fact little more than political and historical illiteracy, mingling with a hack columnist's instinct for provocation. (Whitlock essentially copped to it during the 2008 presidential election, when he wrote a guest column for The Huffington Post entitled "I Owe My Interest in American Politics to Sarah Palin." The piece isn't nearly as bad as the headline would indicate, but in it Whitlock comes off like your libertarian college friend explaining why he doesn't vote.)

Whitlock isn't a Tom; he's a low-information guy, infinitely suggestible, learning on the fly, joining in on a conversation in a language he has no interest in learning. After declaring Chait the winner in the Great American Black Pathology Debates, he turned around and praised Coates's epic case for reparations in the Atlantic, which relied on many of the same arguments he'd made with Chait. "Brought me to tears," Whitlock tweeted.

Given his lack of intellectual curiosity, the astonishing thing with Whitlock is that he's ever right at all. And yet he is, often. To explain this, we can look to the third of his journalistic heroes, the man who, along with Royko and Wiley, "most influenced my career and perspective," according to Whitlock: David Simon.

Simon is an author and journalist who started off as a police reporter at the Baltimore Sun, where he covered crime. He parlayed his reporting experience and expertise into The Wire, HBO's epic series about the decline of Baltimore in particular and the American city in general. The drug war, the police, the dockworkers, the schools, City Hall, the media—all were part of the same narrative about the way institutions, in their brute efforts to perpetuate themselves, fail the people they're intended to serve.

Whitlock looks as The Wire as a text—he's called it his Bible. He still references The Wire in his articles, and he sends fans entire boxed sets that he buys himself. The show changed how he sees the world. Growing up and through most of his adulthood, for example, Whitlock was a self-proclaimed homophobe, but on a 2012 podcast with Simon, the columnist revealed that Omar, a gay stickup man on the show, was what turned his bigotry on its ear.

"Nobody has more influenced me and brought me to a healthier understanding of homosexuality and just the character of homosexual people than the character Omar," Whitlock told Simon. "To me, he was just the highest-character person on the show, the person I would choose to be friends with from the show."

The Wire is all over Whitlock's smartest work, even when it's not explicitly referenced. It's there in his columns about the futility of our war on PEDs; it's there whenever he writes about the NCAA, the perfect illustration of David Simon's model of institutional failure; it was there when he wrote about ESPN and its opportunistic coverage of Bernie Fine.

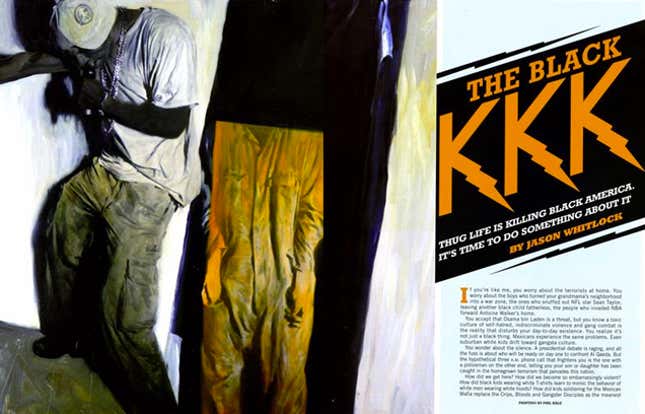

And it was there in what one friend of Whitlock called "maybe the best piece he's ever written in his life." In 2008, Whitlock addressed himself at length to the drug war, the country's prison-industrial complex, and their effects on the country's black population. He worked on the story for months. He bled into it, ultimately producing 5,000 reported words on the subject for Playboy. The magazine ran it in its June issue, and teased it on the cover, and that's where things went to shit.

"The Black KKK," it read. Whitlock's name, in neon, was just beneath. Inside the magazine, a sub-headline read, "Thug life is killing black America. It's time to do something about it."

Whitlock was pissed. "The story isn't about the Black KKK," he wrote in the Star, before the magazine had hit newsstands. "The words do not appear in the 5,000-word column. None of the sources quoted in the story or spoken to on background ever heard those words come out of my mouth, and they never spoke them to me." He accused Playboy's editorial director, Chris Napolitano, of "stirring a racial controversy." Another betrayal.

He had a point. The story was about mass-incarceration approach to drug policy and its trickle-down effects on black people and their culture, and for the most part it was a good, holistic examination of an ongoing national scandal. But it was also a Jason Whitlock story. If there's one thing that consistently characterizes Whitlock's writing about race, it's his dumb and fundamentally patronizing insistence that pop culture is the governing force in the lives of black people, not the residue. The causations start running backward. And so, in the Playboy piece, there were the usual allusions to a "culture of self-hatred" and "gangsta rap and the glorification of prison values." Having correctly identified the violent imagery of certain kinds of hip hop as a symptom of the country's bad policy, he turned around and suggested that the music alone had the power to "define black people and black culture as criminal and worthy of mass incarceration."

Whitlock also wrote, in what was apparently a "spicier lead" than the one he'd originally filed, "How did black kids wearing white T-shirts learn to mimic the behavior of white men wearing white hoods?" He didn't quite say black KKK—a term he'd used before, in reference to Sean Taylor's killers, to the polite applause of conservative writers—but he came close enough that it's hard not to feel, perhaps a little unfairly, that the shit-stirrer got exactly the shitty headline he deserved.

The more people I spoke with for this story, the more I became convinced that the problem with black Grantland, the reason for its sluggish start, the reason it's talked about in some corners of ESPN as John Skipper's unaccountable folly, is the larger-than-life writer at the core of the project. I talked to a dozen writers and editors whom I'd heard were being recruited. Over and over they related the same story, of young talent having to decide between taking the opportunity and paycheck of a lifetime, and working for a man who made his bones disparaging people like them to an audience of approving racists.

That's the bitch of it for Whitlock. Only someone like him, a black pundit with acceptably heterodox views on race who prescribes a sort of cultural austerity program for his own people, thus telegraphing his seriousness on the issue, would have gotten an opportunity like this. He rose to a position where he gets to speak for black people largely by being the kind of commentator black people would never want speaking for them.

"Being a [minority] sportswriter sucks," said one writer. By hiring Whitlock to run his own site, the writer went on, "ESPN found a way to make it more demeaning."

This wasn't an easy story either to write or report. Few people were willing to talk on the record, partly out of a fear of antagonizing a famously vindictive man who now possesses hiring and firing power at one of the country's most powerful media companies. There is also an unspoken rule among blacks in media that you don't bag on one another in public, and it's certainly not lost on me that I'm now several thousands words deep on the wrong side of the taboo.

What I keep going back to, though, is those last couple of conversations with Whitlock, to the feeling he left me with. His first instinct, in trying to dope out a grand conspiracy against him, was to think I was merely a sockpuppet for my editors. He was disregarding or outright denying my own agency. Out of some personal insecurity, he was reducing me to a non-entity, to the sum of other people's dark self-interest, which I was apparently too stupid to see for myself. In the casual dehumanization of it all, in his eagerness to shrink me down to the size and shape of some stock character in the psychodrama in his head, it was a little like being trapped inside a Jason Whitlock column. You might also call it a betrayal.

It's almost certain I won't ever be a part of black Grantland, whatever form it takes. But I want the site to succeed. I want the site to become something like what Rembert Browne, a black writer at Grantland, described for me. "I would love if a site full of black people was writing about everything, writing about stuff that is not a pointedly black, race issue," he said. "That's new. That's not, 'Oh, this is a black site, black people.' It's not, 'Let's talk about rap. Let's talk about racial profiling.'

"Black people are interested in everything," he went on, laughing. "Real talk, we are so dynamic. We're interested in so much stuff."

I want a site that acknowledges that, one that offers a platform and the resources for black editors and black journalists to stretch out and exercise their own agency. I want a site that helps change the conditions that create and nurture and reward hacks like Whitlock. I want Whitlock to succeed so that one day, maybe, there will be no more Whitlocks.

Top image by Jim Cooke.