Lift, squeeze, sniff. It's a ritual millions of us perform every day in the produce aisle of the grocery store, rejecting the blemished and irregular in search of an ideal seldom found on any farm.

Forty percent of all food is never eaten, and this rejection of "ugly food"—the misshapen or imperfect produce that gets thrown out before it ever hits the supermarket display—is a major contributor to food waste. Most of that waste happens on the consumer side: food rejected by shoppers or by the markets before it reaches their aisles, or rejected in restaurants before it reaches our tables. Doug Rauch, the former president of Trader Joe's, thinks he has the answer. This summer he is opening a store in Boston, called Daily Table, that will make outdated and blemished food friendly and attractive. His "hybrid between a grocery store and a restaurant"—with both fresh produce and prepared, "speed-scratch" dishes with prechopped vegetables, cooked proteins and rice that's ready to eat, requiring just sauce and seasoning—is a pilot project attempting to recast the social norms of what's fresh, desirable and edible.

The project grew out of a fellowship Rauch started at Harvard in 2010, following the end of his tenure at Trader Joe's. One in six Americans, he discovered, is not eating enough nutrients. "They can't afford to get the food they need," he explains, adding that what they eat is "calorically dense, but nutritionally stripped." The health care tsunami that follows—early-onset diabetes and heart disease, even in children and teens; additional health care costs of half a trillion dollars over the next two decades due to rising obesity—makes it everyone's problem. Malnutrition, paired with the problem of food waste that he saw firsthand at Trader Joe's, got him thinking.

At a recent conference in Washington, D.C., put on by the Partnership for a Healthier America, Rauch shared a panel called "Feed Families Not Landfills" with Tim York of Markon, a company that distributes billions of dollars worth of produce across the U.S. "He showed a photo of a field of romaine lettuce—10 acres of it, beautiful," Rauch remembers. "The photo was the field after the harvest. They'd harvested all the lettuce that was the right size for bagged lettuce, but there was a ton out there that was two inches too tall or too short, and that gets plowed under. All of the things that are not the right size, color, shape—a lot goes rotten, gets plowed under or goes to compost."

Rauch wondered if he could open an attractive retail store, partner with grocers and producers to source the surplus food that might not be perfectly beautiful, present it well and price it competitively with junk food. A dime for an apple, say, instead of a buck?

"We let perfect be the enemy of the good: If we go into store and see an avocado that is blemished or misshapen, we'll pick the one next to it," Rauch says, "but we make exceptions in two cases. One, we call it heirloom. It can be funky-looking, and should be. And two is the farmers' market. You don't expect apples to look like they do at Whole Foods. You'd be suspicious. What's interesting is that we instinctively know that things in nature aren't supposed to look like this."

The idea at Daily Table is to create an atmosphere akin to a farmers market. "In the real world, carrots will often have two legs rather than one, but you never see those in the grocery store, because they're almost always thrown out," says Nathanael Johnson, food writer for Grist and the author of All Natural, a book that debates when "natural" is really healthy. "We've become so alienated from our farms that we can no longer assess the healthfulness of our food. Instead, people gravitate toward external perfection."

Daily Table will also tackle the problem of sell-by date versus expiration date. "When a grocer sells you a gallon of milk, if it says sell by April 2, it doesn't mean that you have to go home and drink it that night," Rauch says. "Generally, it will last a week after that. Most Americans don't know that. So we are disposing of perfectly good food that's healthy and wholesome." Consumer education is part of his mission; the store will work with quality assurance food labs and manufacturers to determine conservative "use-by" dates, giving customers information on what they mean, as well as plenty of time to use products.

Europe is in the vanguard when it comes to hip-ifying ugly food. The EU has designated 2014 the "European Year Against Food Waste." After a British member of Parliament, Laura Sandys, set up a company to encourage the sale and use of oddball fruits and vegetables—food should be valued for nutrition, she said, "not whether it is fit for a catwalk"—the supermarket giant Sainsbury's changed rules governing the aesthetic appearance of its fresh produce. Last year, the rebranding of ugly food came to pass in Switzerland (with a brand called Unique) and Germany (a line called Wunderlinge, with a meaning approximating "anomaly" and "miracle"). The produce is cheaper, and goes fast. Recently, three German graduate students cooked up the idea for a trendy grocery that sells only ugly fruit.

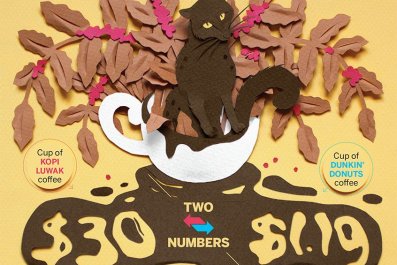

A recent report commissioned by the U.K. global food security program shows that of a given crop of fruit or vegetables grown in the country, up to 40 percent is rejected because it doesn't meet retailer standards on size or shape. That's a sizable chunk of the $31.3 billion of food that gets jettisoned in Britain every year. American supermarkets lose $15 billion each year in unsold fruits and vegetables. American consumers like their apples red and their bananas unspotted, so grocery stores comply—sometimes even dyeing and cutting to fit.

Changing mainstream culture to accept a crooked cucumber has bigger implications than just cost. Given that 20 to 30 percent of greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture, food waste is a huge piece of the global climate problem. Last month, a new study by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change revealed scientists' deep concerns about dropping agricultural production—as much as 2 percent per decade for the rest of the century. The panel's researchers have also found that though minor improvements can be made to improve efficiency in agriculture, the real game changers will lie on the consumption side.

"The best forecasts I've seen suggest that we are going to have to double agricultural production by 2050," says Johnson. "Doing that without cutting down the rain forest is going to be a tremendous challenge—especially given that climate change is actually driving farm productivity down." The single best idea for solving this problem, with the lowest costs and fewest trade-offs? Stop throwing away so much of the food we grow.

So in the short term, the issue looks skin-deep: Ugly food is just as good as pretty food, and it's easier on the wallet. In the long term, a preference for ugly may shore up our global food supply.

"Is it possible to tell the story and have people better educated and smarter about buying food?" Rauch asks. "The difference between that sell-by date and when the food is no longer edible can feed a huge population." And in an environment in which healthy food is often priced at a premium (part of why Whole Foods is sometimes called "Whole Paycheck"), he's doing it at a price affordable to people who need it most.

"The doors," he says, "are open to everyone."