Only God Can Stop Public Urination

How ceramic tiles could keep Indians from treating the streets as a urinal

I recently noticed something curious as I drove out of my neighborhood in South Delhi. The road had just been redone and now, on the stone walls that run along either side of the street, about knee-high off the ground, I spotted ceramic tiles with pictures of Hindu gods. There were images of Lakshmi, Shiva, Saraswati, Hanuman, and others of the pantheon, along with saints like Shankaracharya and Sai Baba of Shirdi.

Why, I wondered, were these god tiles there? Perhaps they were intended to beautify; placed about three feet apart, they certainly brightened up the otherwise nondescript walls. Or maybe they were inspired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent election and the corresponding swell of Hindu pride. Or they could have been spare gifts for the Hindu festival of Diwali—even donated leftovers from someone’s home renovation.

Then a wise, old soul, in the guise of a neighbor, gently explained their purpose to me. The tiles were there to address a problem that has long plagued India, from Kashmir in the north to Kanyakumari in the south: public urination.

It’s a public-health hazard and a ubiquitous eyesore that has invited corrective measures ranging from fining offenders to beating drums at those caught in the act to spraying them with water cannons, with limited success. And it’s a fact of life in India that initially shocked me when I moved here some nine years ago, but one I’ve gradually learned to ignore. Chalta hai. Whatever.

Some defend the practice, arguing that it stems from India’s severe lack of toilets (nearly half of Indian households don’t have access to a toilet, and figures such as Modi and Bill Gates have pledged to rectify the shortage). But that’s only partly true. Most visible roadside urinators are men. And even when women do pee in public, they often aim into the ground. Men, it seems, prefer to have something solid to relieve themselves against—perhaps for the reassurance that they’re not merely pissing into the wind.

That’s where the god tiles come in. I found out that my local residents’ association was responsible for installing the tiles in our neighborhood, in the hopes that people would refrain from peeing on a picture of a god or within the god’s benevolent but omniscient gaze. It’s an ingenious way to keep the roads—or at least that particular stretch of road—free of pee. The tiles are durable, inexpensive, difficult to steal, and easy to clean and install. The psychology behind why they work is complex. It could be a combination of fearing the wrath of God (especially when one’s pants are down, or even just open) and wanting to seem RC (religiously correct).

I’ve since learned that god tiles aren’t only deployed to stop public urination. In some office buildings, for example, god tiles have been installed in stairways to keep people (OK, mostly men) from spitting on walls. They’ve also been used to prevent people from throwing garbage in certain places.

If these tiles are indeed effective in deterring public urination (solid evidence of their success is difficult to come by, though some seem convinced of their value), could they help discourage other bad behaviors? Imagine installing god tiles on the desk of every politician in parliament to prevent corruption, or in the offices of government servants to ensure that they actually serve. Or at traffic lights, just above the countdown clock, to encourage people to spend that red-light minute in quiet prayer, rather than plotting how to break all the traffic rules.

My daughter, a firm believer in national integration, has suggested that these god tiles also include Muslim, Christian, and Sikh iconography. After all, if there’s one thing Indians have in common, it’s their god-fearing—or at least god-respecting—nature (polls reveal that roughly 90 percent of Indians view religion as an important part of their lives). I wonder what would happen if I placed a few god tiles around my daughter’s room; after all, messiness cannot be next to godliness.

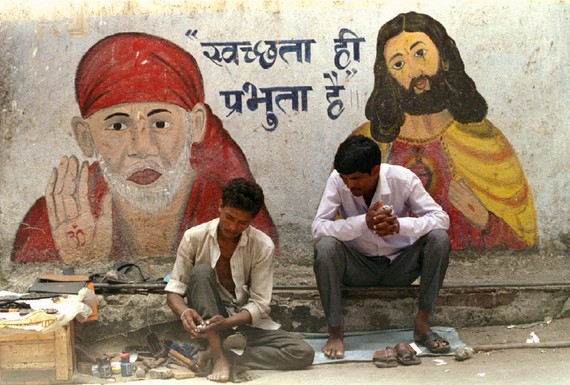

In fact, the concept has already expanded to several faiths. In documenting how tiled Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and Sikh gods arrived in Mumbai’s streets (they replaced or supplemented written messages ranging from the polite “please do not sully the wall” to the more aggressive “son of an ass, don’t pee here”), the Indian photographer Amit Madheshiya recently marveled at the “harmonious existence for the gods” in such “cluttered and messy spaces”—especially in a predominantly Hindu country that “is often irreversibly divided along the coordinates of religion.”

Unfortunately, panaceas are rarely perfect. The other day, as I was leaving my neighborhood, I spotted a man on the same road urinating against those same walls. I was shocked. Who could be so bold as to disregard the presence of all those gods? And then it dawned on me: He might be an atheist.