Half a century ago, following race riots in Newark that left a nation reeling, the president of the United States appointed a commission – a panel with all the gravitas Lyndon Johnson could give it, and the mission of taking America’s “race conversation” head-on. That body that issued this sharp, devastating conclusion: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal.” The only way to avoid this fate, the so-called Kerner Commission declared, would be a response “compassionate, massive and sustained” – action that would require of every American “new attitudes, new understanding, and above all, new will”.

For the next two decades, the United States mustered the will to continue the process of desegregation and moved toward closing racial gaps in wealth, income and education. But then, fired by the “culture wars”, it began to undo this consensus for racial justice. Predictably, the gaps got worse, and since the late 1980s, we have seen an attendant rise in resegregation.

In 1997, after a decade of these wars, President Bill Clinton signaled a possible change – perhaps even a waning of hostilities – when he announced an “Advisory Board on Race” to advise him “on matters involving race and racial reconciliation”. Clinton recast Rodney King’s famous question – “Can we all just get along?” – by asking: “Can we become one America in the 21st century?”

Although Clinton’s panel convened hundreds of meetings and developed dozens more recommendations, it merely called on Americans “to accept and take pride in defining ourselves as a multi-racial democracy”. The board’s rollout was eclipsed by the Monica Lewinsky affair, because Americans would rather talk about sex and scandal than about race and equality.

Ever since, from Barack Obama’s audacity of hope to the burning despair that accompanied Darren Wilson’s non-indictment this week, the “race conversation” has become less a reality than a rhetorical device. Every time toxic, tragic events – a killing, a fire, a riot – reveal the unequal ways that different Americans experience resegregation and state violence, we talk about having a productive conversation, but we never really have it.

Instead, we have reverted a half-century in our racial progress. Nationally, public schools are returning to levels of resegregation unseen since Brown v Board of Education. Urban gentrification debates are really about the displacement of people of color, who are often forced to move into aging, overwhelmingly non-white suburbs such as Ferguson, Missouri, or Sanford, Florida, where Trayvon Martin was killed by George Zimmerman.

And so we go on talking about talking, and mostly we go through the motions. When a celebrity or rich person says something explicitly racist, we make a noisy ritual of shunting them to the wings. We are able to do this because the multiculturalism movement succeeded in changing the rules of civility. It has taught us what not to say to each other, but not what to say next.

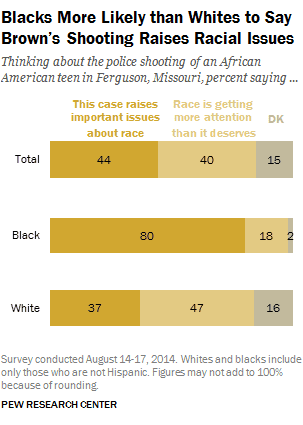

It’s about time we agree that this is a conversation worth having. Recent polls show that white Americans depart from black and Hispanic people in their views of the Michael Brown killing, as well as on policing and protest. But white people also differ from people of color on how to talk about race. A recent Pew research poll found that 80% of African American and 50% of Hispanic Americans felt the Michael Brown killing raised important issues worthy of discussion. By contrast, only 37% of white people agreed, while almost half felt race was receiving too much attention. One group’s invitation to a conversation, it seems, is still another’s cue to exit the room.

Mari Matsuda, a law professor at the University of Hawaii who testified before Clinton’s panel in 1997, tells me that the mainstream discussion has not changed much. “The disdainful eyeroll, the plea – ‘Can’t we stop talking about race?’ – are commonplace,” she said this week, after the non-indictment in Ferguson. “‘Get over it’ is the surface discourse, while police killings and voter suppression are the material reality.”

Americans of all backgrounds, the political pollster Cornell Belcher argues, share certain nationally defining values: freedom, fairness, opportunity, equality. “However, this is the problem with equality,” he told me. “In certain groups, it triggers a conversation that goes like this: ‘They’re trying to get equality, which means I’m losing something.’”

“You have to be very careful about triggering this fear of ‘us versus them,’” Belcher says. “I can’t answer: ‘How do you address this issue of inequality without having the race part of the discussion?’ That is what’s not easily reconciled now in our politics.”

That might seem like a counterintuitive idea in a culture that appears desegregated, when you need only turn your TV to ABC for Black-ish on Wednesdays or three hours of “Shondaland” on Thursdays to see families and women of color in central roles. But one kind of representation does not automatically lead to the other. Our politics still reconcile themselves under the long shadow of the Southern Strategy, the Nixon-era political realignment that has left us with a two-party system that mirrors patterns of resegregation and produces the pendulum swings of “wave elections”. Such swings inevitably turn on white anxiety over demographic and cultural change. Our silence gets filled by demagogues who profit from the politics of division.

When Obama was elected, many hoped for a kind of racial peace. Instead, his time in office has been marked by a resurgence of the culture wars, as the symbol of hope became the symbol of things to be feared: a Muslim, a socialist, an illegal alien. We are left with a do-nothing politics that makes change on most racial justice issues – from immigration to housing to the wealth gap – seem unimaginable.

But the Obama years have been characterized by a return to community and cultural organizing, enough for any historian to see an opportunity. “This is the gift young people in the streets have given us,” Matsuda says. “They have made it their calling to let no murder go unnoticed, no name forgotten.” Those protesters in Ferguson are already making history, by restarting “the race conversation” for real.

This past week, Missouri governor Jay Nixon officially launched the so-called “Ferguson commission” made up of 16 people (three under 30 and nine African Americans) to “conduct a thorough, wide-ranging and unflinching study of the underlying social and economic conditions” – and, of course, to offer yet more recommendations, starting with a meeting on Monday. Attorney general Eric Holder has announced he will hold city-by-city meetings to discuss race relations and issues of policing.

But for the latest commissions and convenings to have any impact, we need to be having some real talk ourselves – honest, empathetic dialogue about the long-term impact of resegregation and inequality. If we insist that the politics of racial division will no longer work, we can start to imagine the outlines of a new consensus for racial justice and focus on our shared future, rather than merely await the next toxic, tragic set of events.

Until we have a will, there is no other way.

- Share your Ferguson solutions: No justice, no peace, what now? Join the conversation with #FergusonNext and at FergusonNext.com