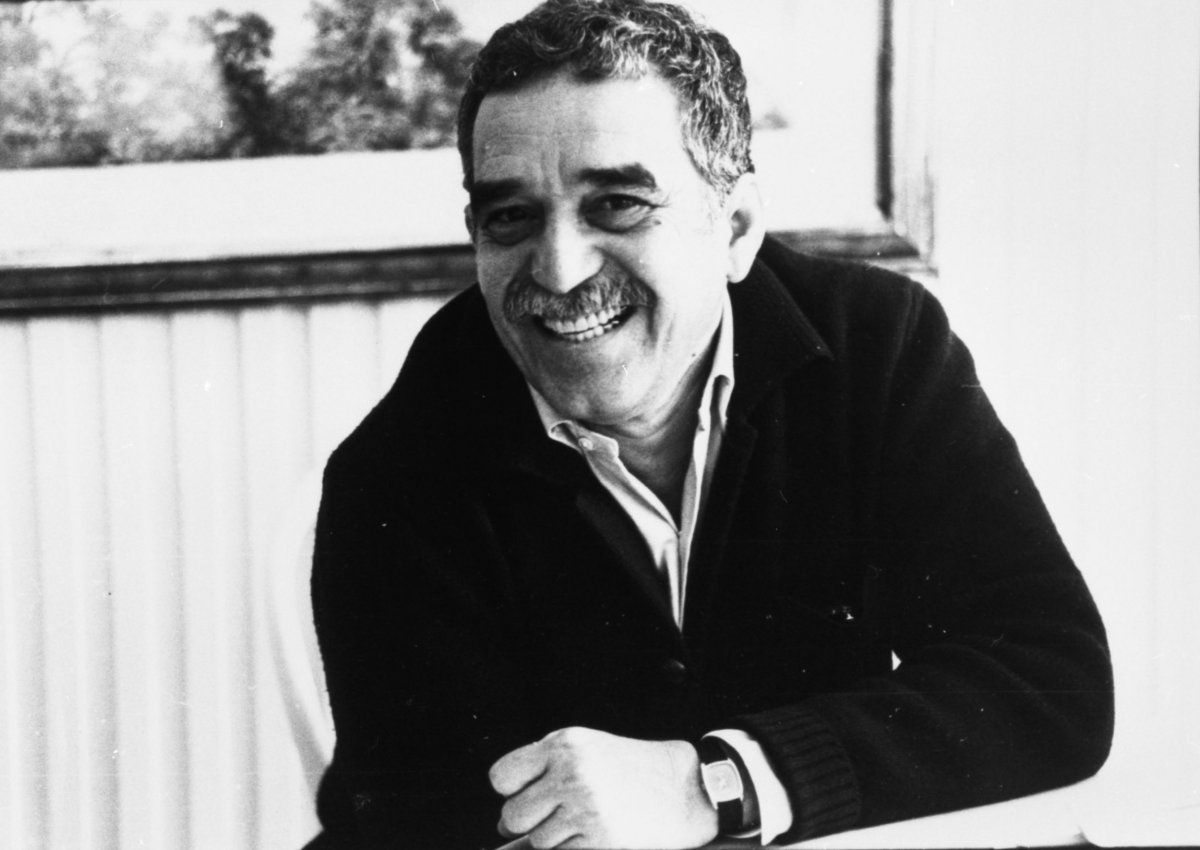

The late Gabriel García Márquez holds a special place in the hearts of journalists.

Like Charles Dickens, Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway—or contemporaries like Pete Hamill and Tom Wolfe—García Márquez, a titan of 20th century literature, honed his writing skills as a reporter before he became a celebrated novelist.

Even as his literary star rose, García Márquez, known colloquially across Latin America as Gabo, spoke proudly, tenderly and frequently about journalism.

"Those who are self-taught are avid and quick, and during those bygone times, we were that to a great extent in order to keep paving the way for the best profession in the world…as we ourselves called it," said García Márquez during a speech about journalism at the 52nd Assembly of the Inter American Press Association in 1996.

García Márquez, whose novels transported tens of millions of readers to magical, formidable and melancholy worlds, died in Mexico City on Thursday. He was 87. The Nobel laureate had been ill for some time: He contracted lymphatic cancer in 1999, and in the last few years of his life battled dementia.

In one of his earliest assignments as a reporter, García Márquez, who was born in the small Colombian town of Aracataca in 1927, described the aftermath of a mudslide in Medellín that buried at least 100 people, according to local reports.

"Propelled by confusion and bewilderment, half a hundred curious onlookers who gathered on the rocky ledge were divided into two groups: one ran left, the other right," García Márquez wrote in the 1954 story for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. "If, rather than do that, they had remained immobile, quite probably they would have lived, because just before getting to the ledge, the mudslide branched off."

He followed Jorge Alirio and Licirio Caro, 11- and 8-year-old brothers, who lived in the "picturesque and tortuous neighborhood of Las Estancias, that looks like a Nativity scene with its houses built into the mountain." Their mother, Maria Caro, was about to wash clothes before she was buried; their sister, Amparo, 9, was sweeping the floor; their 8-month-old brother was still asleep.

García Márquez let his imagination run wild with what-if scenarios throughout the story of what some news programs at the time called "the worst tragedy in the history of the country." Offices had closed at noon, and most employees headed to the highway to Ríonegro. "If another mudslide had happened then, over a tightly-packed and unsuspecting mass of employees, students, laborers, peasants, businessmen and bystanders with unknown professions, there would have been more than a thousand victims," García Márquez wrote.

The bespectacled author earned 900 Colombian pesos a month when he started working at El Espectador, which allowed him to live very comfortably and still help his parents, wrote Jacques Gilard in the prologue to Entre Cachacos, a compilation of García Márquez's published articles during 1954 and 1955. He was both a movie critic and a reporter at El Espectador's Bogota office.

Those years, he said, set a foundation for his career in literature, which established the magical realism genre.

"Fiction has helped my journalism because it gives it literary value. Journalism has helped my fiction because it has kept me in a close relationship with reality," García Márquez said during a 1981 interview with Peter H. Stone for The Paris Review.

During the interview, García Márquez praised John Hersey's piece on Hiroshima, published in The New Yorker in 1946, as "exceptional" and said he would like to report on Poland but was deterred by its frigid weather.

The year after García Márquez's article on the landslide was published, eight members of Colombia's Navy who were traveling aboard the Caldas, a destroyer, from Mobile, Ala., to Cartagena, Colombia, fell overboard. They were declared dead after a four-day search, but a week later, one of the soldiers, Luis Alejandro Velasco, was found alive and immediately hailed a hero.

Shortly after, Velasco, 20 at the time, walked through the doors to El Espectador's newsroom to tell his story. García Márquez sat with him for 20 days, six hours at a time, and interviewed him, "taking notes and dropping trick questions to detect contradictions," García Márquez wrote years later.

The story, written in the first person, ran in the paper as a 14-part series and revealed details that angered then-president and dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla. The ship had been carrying contraband cargo, including televisions and washing machines, wrote García Márquez. The government retaliated against El Espectador, which shut down a few months later. Velasco had to abandon the Navy and "went over a precipice of the oblivion of common life," wrote García Márquez, who was dispatched to Geneva, Rome and Paris as a correspondent shortly after.

It wasn't until 1970, when Velasco's account of his 10 days at sea with no food or water was published as a book, The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor, that García Márquez's name was officially associated with the narrative for the first time.

After a short stint in Western Europe, García Márquez traveled to East Germany, Moscow and Prague. He wrote "90 Days in the Iron Curtain" and published it in Cromos magazine in 1957. That year, he moved to Venezuela, where he worked for several magazines.

A decade later, One Hundred Years of Solitude, the crowning achievement of his half-century-long literary career, was published. He began devoting most of his time to writing novels after the unfathomable success of the multigenerational story of the Buendia family, but would dip into journalism from time to time. In 1977 he chronicled Cuba's participation in the Angolan revolution in a story titled "Operacion Carlota."

García Márquez, whose younger brother, Eligio, was also a journalist, established the Foundation for New Latin American Journalism in Cartagena in 1994. The foundation offers workshops to young reporters.

In the 1996 speech at the Inter American Press Association, he described journalism as "an incomprehensible and voracious profession" that "does not concede one instant of peace."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Karla Zabludovsky covers Latin America for Newsweek. Previously, she reported for the New York Times from Mexico, covering regional politics, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.