Get Rich, Live Longer: The Ultimate Consequence of Income Inequality

The income gap meets the longevity gap.

Brookings economist Barry Bosworth crunches the data on income and lifespans for the Wall Street Journal, and the numbers tell three clear stories.

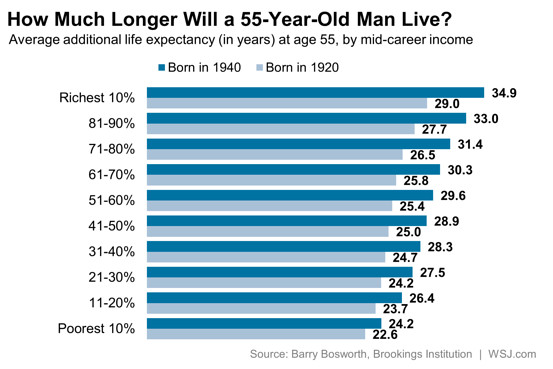

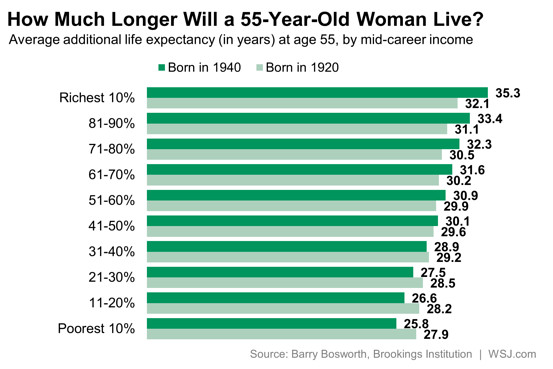

1. Rich people live longer.

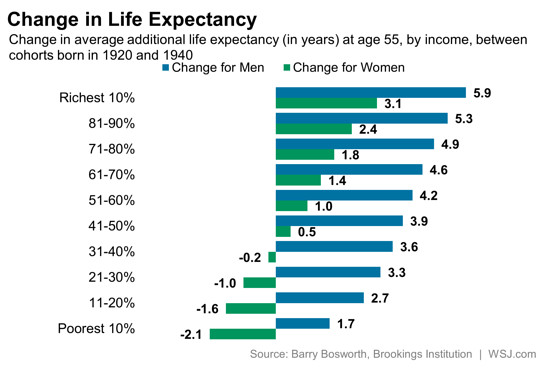

2. Richer people's lifespans are growing at a faster rate.

3. The problem is worse for women than for men.

First, let's look at the guys. A rich man (top decile) born in 1940 can expect to live 10 years longer after he turns 55 than a poor man (bottom decile). That longevity gap grew by four years in one generation.

Women live longer than men, overall. But their inequality gap getting worse. A rich woman at 55 can expect to live a decade longer than a poor woman, too. But this gap grew even more between the Silent and early Boomer generations, by six years.

Here's the money chart and it tells a really sad story. In the richest country in the world, the expected lifespan of middle- and lower-income women is actually declining. At every income level, more money means more life.

A few thoughts and implications:

1. Causality: This is your obligatory correlation-is-not-causation caveat. It's intuitive that being rich gives you access to better food, more social connectivity, and higher-quality health care. But this data does not prove that making another $10,000 literally buys you additional months of life. Confounding variables abound. For example, poor people are more likely to be smokers, for a variety of cultural and tax reasons, and smoking kills you faster, no matter what AGI you fill in on your tax forms.

2. Geography: Annie Lowrey reported that the sorting of zip codes into rich and poor means you can have two counties divided by 300 miles and more than 20 years of expected life. The typical guy in McDowell County, West Virginia, makes less than $30,000 a year and doesn't live to 65. Five hours north on the highway, a typical man living in Fairfax County, Virginia, makes more than $100,000 and lives more than 80 years. The two Virginian counties are two different countries.

3. Policy: When somebody in Washington proposes raising the retirement age for Social Security or Medicare, he typically says something like: "We can afford it, because we are living longer." Yes, We can afford it, when the We in that sentence applies to an audience of white rich old men and women who really are seeing their lifespans grow by leaps and bounds. But We doesn't apply to the millions of poor women whose lifespans are actually declining. Raising the Social Security retirement age disproportionately reduces lifetime benefits for the very people Social Security was invented to protect. Jordan Weissmann and others have made this point before.

4. Morality: We know a few things about money and life. We know that market wages (pre-tax, pre-transfer) are flat-lining or falling for middle- and lower-income Americans thanks to globalization, technology, marriage- and geographical sorting, the decline of unions, and other reasons. We know that poorer Americans live shorter lives and that poorer women live shortening lives. We don't know the precise causal mechanism, but we know that the relationship is remarkably tight at every income level. We also know that the intellectual leader of one of the two major parties has repeatedly produced a budget that would cut taxes and transfers in such a way that middle- and lower-income people would necessarily suffer a loss of government-transfer income that we have little expectation to be made up in the growth of market wages. (Two-thirds of Paul Ryan's budget cuts are for income-transfer programs.) I'll leave it for you to decide, based on what we know about income and lifespans, whether a program that would necessarily make the low-income lower-income is one that deserves to be taken seriously as a moral document.