Stanley Kubrick actually made the transition from photography to film after reading Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Film Technique. Pudovkin was a Russian film director, screenwriter and actor who developed influential theories of montage. Pudovkin’s masterpieces are often contrasted with those of his contemporary Sergei Eisenstein, but whereas Eisenstein utilized montage to glorify the power of the masses, Pudovkin preferred to concentrate on the courage and resilience of individuals.

You’ve quoted Pudovkin to the effect that editing is the only original and unique art form in film.

I think so. Everything else comes from something else. Writing, of course, is writing, acting comes from the theater, and cinematography comes from photography. Editing is unique to film. You can see something from different points of view almost simuluneously, and it creates a new experience. Pudovkin gives an example: You see a guy hanging a picture on the wall. Suddenly you see his feet slip; you see the chair move; you see his hand go down and the picture fall off the wall. In that split second, a guy falls off a chair, and you see it in a way that you could not see it any other way except through editing. TV commercials have figured that out. Leave content out of it, and some of the most spectacular examples of film art are in the best TV commercials.Give me an example.

The Michelob commercials. I’m a pro football fan, and I have videotapes of the games sent over to me, commercials and all. Last year Michelob did a series, just impressions of people having a good time—The big city at night—

And the editing, the photography, was some of the most brilliant work I’ve ever seen. Forget what they’re doing—selling beer—and it’s visual poetry. Incredible eight-frame cuts. And you realize that in thirty seconds they’ve created an impression of something rather complex. If you could ever tell a story, something with some content, using that kind of visual poetry, you could handle vastly more complex and subtle material. —Stanley Kubrick, The Rolling Stone Interview

Here’s that great quote, courtesy of Film School Thru Commentaries.

The most influential book I read at that time was Pudovkin’s Film Technique. It is a very simple unpretentious book that illuminates rather than embroiders. It certainly makes it clear that film cutting is the one and only aspect of films that is unique and unrelated to any other art form. I found this book much more important than the complex writings of Eisenstein. —Stanley Kubrick, Pudovkin and real life

DOWNLOAD: Film Technique and Film Acting.

Kubrick was influenced by the tracking and “fluid camera” styles of director Max Ophüls, and used them in many of his films, including Paths of Glory and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick also noted how in Ophuls’ films “the camera went through every wall and every floor.” He once named Ophüls’ Le Plaisir as his favorite film. According to film historian John Wakeman, Ophüls himself learned the technique from director Anatole Litvak in the 1930s, when he was his assistant, and whose work was “replete with the camera trackings, pans and swoops which later became the trademark of Max Ophüls.”

Highest of all I would rate Max Ophüls, who for me possessed every possible quality. He has an exceptional flair for sniffing out good subjects, and he got the most out of them. He was also a marvellous director of actors. —Stanley Kubrick in an interview by Cinema magazine in 1963

You’ve been quoted as saying that Max Ophuls’ films fascinated you when you were starting out as a director.

Yes, he did some brilliant work. I particularly admired his fluid camera techniques. I saw a great many films at that time at the Museum of Modern Art and in movie theaters, and I learned far more by seeing films than from ready heavy tomes on film aesthetics. —An Interview with Stanley Kubrick (1969)

Recommended viewing: Max Ophüls’s friends and family paying him tribute under a circus tent in Cinéastes de notre temps: Max Ophuls ou Le plaisir de tourner (1965).

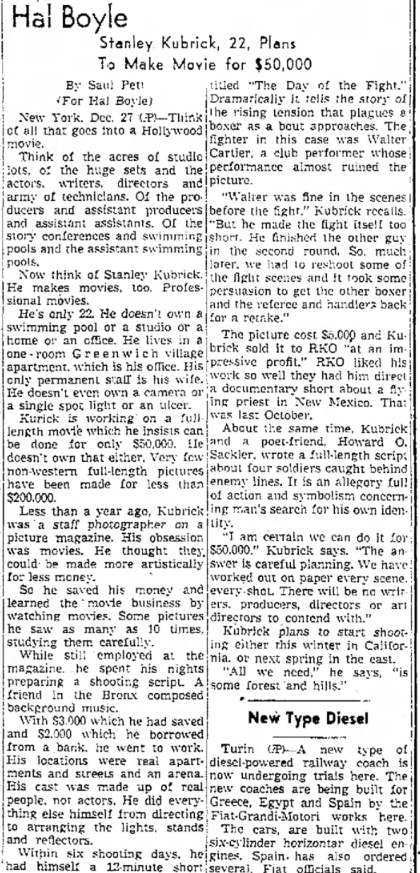

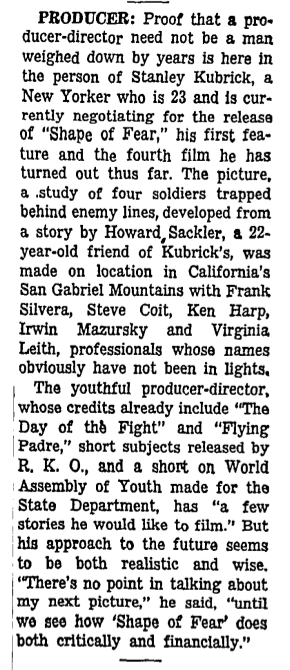

“All we need is some forest and hills.” Eric Burritt shared a great vintage article on how 22 years old Stanley Kubrick planned to make his first feature film, Fear and Desire.

If you were nineteen and starting out again, would you go to film school?

The best education in film is to make one. I would advise any neophyte director to try to make a film by himself. A three-minute short will teach him a lot. I know that all the things I did at the beginning were, in microcosm, the things I’m doing now as a director and producer. There are a lot of noncreative aspects to filmmaking which have to be overcome, and you will experience them all when you make even the simplest film: business, organization, taxes, etc., etc. It is rare to be able to have an uncluttered, artistic environment when you make a film, and being able to accept this is essential. The point to stress is that anyone seriously interested in making a film should find as much money as he can as quickly as he can and go out and do it. And this is no longer as difficult as it once was. When I began making movies as an independent in the early 1950s I received a fair amount of publicity because I was something of a freak in an industry dominated by a handful of huge studios. Everyone was amazed that it could be done at all. But anyone can make a movie who has a little knowledge of cameras and tape recorders, a lot of ambition and—hopefully—talent. It’s gotten down to the pencil and paper level. We’re really on the threshold of a revolutionary new era in film. —An Interview with Stanley Kubrick (1969)

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]