For American daily newspapers, the story of the last decade-plus hasn’t been about mass closures — it’s been about mass shrinkage. The pace at which newspapers are shutting down isn’t much different from what it was in the late 20th century. Instead, just about every daily paper has gotten smaller — smaller newsroom, smaller budgets, smaller print runs, smaller page counts — year after year after year. It’s death by a thousand paper cuts.

But shrinking can only go so far. In the second quarter of 2018, McClatchy’s print advertising revenue dropped 26.4 percent year over year; Gannett was down 19.1 percent, Tronc 18 percent. They’re not making new daily print newspaper subscribers anymore, and existing ones either move to digital or shuffle off this mortal coil daily. There’s no Zeno’s Paradox to prevent newspapers from eventually deciding one one of two courses of action: going online-only or shutting down entirely. Even the most pro-print publishers will tell you that, someday, the “cost of print” and “revenue from print” lines will intersect on an accountant’s projection and it’ll be time to stop the presses for good. The only question is when: Two years? Five? Ten? Thirty?

So one of the questions I’m most interested in for the near- to medium-term future is what will actually happen when print newspapers start to disappear in large numbers, whenever that may be. Will those print readers just become digital readers? Will they spend as much time consuming local journalism on their phones as they do at their breakfast tables? Or will their attention wander as readers’ competitive set widens to, well, everything else the Internet can offer?

So I was happy to see some new research by Neil Thurman and Richard Fletcher that offers some insight into those questions. And — while there are a few key caveats I’ll mention — the news is generally not that great. Shutting down print doesn’t drive those readers to print-like consumption habits on digital devices. Instead, they become a lot like other digital readers — easily distracted, flitting from link to link, and a little allergic to depth.

Thurman and Fletcher examine the case of The Independent, the national British daily that, after 30 years in print, went online-only in 2016. What happened to its reach and influence?

There’s a lot of interesting stuff in there, but these are the two key charts, I think. First:

This compares the number of Britons in the total audience of each national newspaper, in the periods before and a year after the Indy’s end of print. If you’re a half-glass-full type, the good news is that The Independent’s total audience was basically flat despite killing off print. The number of print readers it lost and the number of digital readers it gained basically cancel one another out.

If you’re a half-glass-empty type, of course, you’d note that “basically flat” was also the worst performance of any British national daily. (The Sun got rid of its paywall during this period, so it’s a weird outlier. But the average paper’s audience went up about 25 percent.) And you’d note that the “after” period in question includes the aftermath of both Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, each of which fueled a huge increased interest in news.

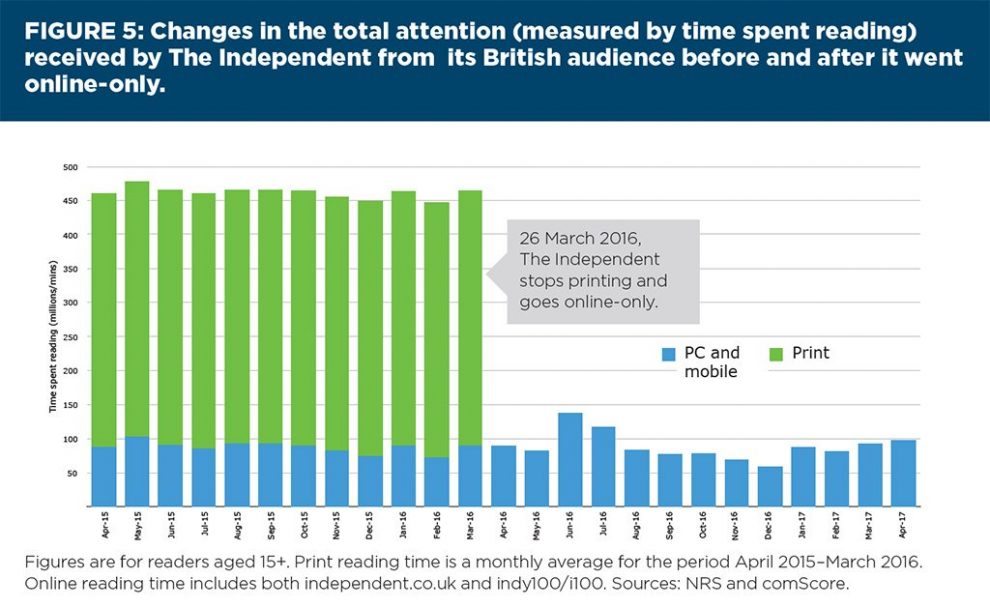

But here’s the really important one:

That first chart was looking at total audience: How many people are consuming Independent content at all, in whatever medium? This second one is looking at total attention: How much total time are Britons spending consuming Independent content, in whatever medium? And this one’s something of a disaster.

When it shut off the presses, The Independent only had about a paid print circulation of about 40,000 — versus 58 million monthly uniques in digital.

58 million sure seems a lot bigger than 40,000! But Thurman and Fletcher found that those few print readers were responsible for about 81 percent of all time spent consuming Independent content. All its digital platforms made up only 19 percent.

Or to put it another way: In an average month, a single print subscription to The Independent generated on average, about 6,100 times the actual content consumption as one monthly unique on its website or app. It’s not a perfect comparison — monthly uniques aim to measure people while circulation measures copies. But the point is crystal clear: Print readers are just far, far, far, far better news consumers than digital ones.

<aside>This is something I find journalists often have a hard time understanding — mainly because they consume a ton of digital news all day and night. In the print days, a reporter’s news consumption and an average citizen’s weren’t all that far apart — mainly because there just wasn’t that much news available to consume. Today, a reporter getting a dozen morning newsletters, listening to a news podcast on the morning commute, getting news alerts on their phone and monitoring Twitter for the latest all day is engaging in very extreme behavior. We’re the outliers. We should be better at remembering that.</aside>

That chart shows that all the time Independent print readers spent just…disappeared when the paper did. It didn’t transition to independent.co.uk. The demand went elsewhere — whether to another news site, a few minutes of Facebook scrolling, Netflix, Fortnite, an afternoon nap, or whatever else caught someone’s attention.

Thurman and Fletcher calculate that, in the 12 months before and after stopping print, the total time spent consuming The Independent dropped from 5.548 billion minutes to 1.056 billion minutes. Of its print readers, half read the newspaper “almost everyday.” Its online visitors read a story, on average, a little over twice a month. Print readers spent, on average, 37 to 50 minutes with each daily edition they read. Online Independent readers spend, on average, 6 minutes a month.

We’ve been hitting on this issue here for many years. Back in 2009, Martin Langeveld did his own back-of-the-envelope calculations and found that only about 3 percent of all consumption of newspaper content was happening online. Most of the same industry trends happening now were already visible then, but those big digital numbers from comScore or Omniture or Google Analytics were already hiding the underlying shift.

In the near-decade since Martin’s piece, I guess that 3 percent has moved to 19 percent, at least for The Independent. Yay? But the dynamic remains unchanged: In print, newspapers had few if any competitors. Online, they have infinite competitors.

As Thurman puts it: “By going online-only, The Independent has decimated the attention it receives. The paper is now a thing more glanced at, it seems, than gorged on. It has sustainability but less centrality.”

Now, there are some good reasons why an American daily going online-only might not exactly match The Independent’s experience. The Independent was one of 13 national print newspapers in the U.K.; while British readers are often quite attached to their particular paper, it wouldn’t be too much of a reach for Indy print readers to become Guardian or Times or Telegraph print readers. If a newspaper in Atlanta or Denver or Houston or Seattle goes out business, there won’t be an easy print alternative to turn to. Also, you can quibble (I have before) with the reliability of survey data estimating print consumption, which can be subject to exaggeration. (People like to say they consume lots of news, just like they like to say they eat lots of vegetables and go to the gym all the time.)

On the other hand, one of the bright spots for The Independent in this study is that it increased its international reach by shifting its focus online. Which makes sense — there’s a giant English-language audience in the United States that is unreachable by a British paper in print but is happy to tap a link now and then. But that increased out-of-market reach is unlikely to come to a typical American metro daily that goes online-only, without a radical abandonment of its local mission. There are only so many people interested in what’s going on in Albuquerque or Fresno or Cincinnati.

Even with those points of difference, though, the overarching lesson holds, I think. Leaving print is the ultimate cost-cutting; a huge share of a newspaper’s cost structure is tied up in building-sized printing presses and Canadian forests and ink by the barrel. But when that day comes — even if it helps a newspaper’s bottom line — its audience isn’t likely to follow along. And that means accepting a dramatic decline in reach, influence, and impact.