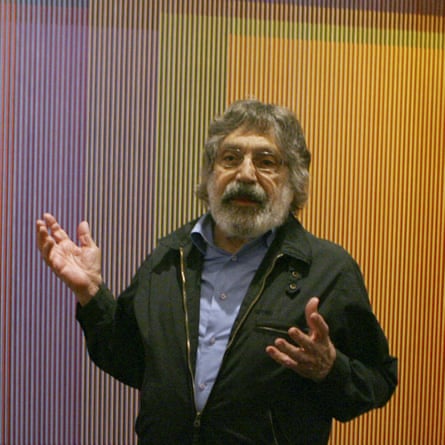

Carlos Cruz-Diez, who has died aged 95, harboured a seven-decade obsession that the common understanding of colour was wrong. “Colour,” the Venezuelan-born artist believed, “evolves continuously in time and space.”

“I want people to realise that colour is not a certainty, but a circumstance,” he said in 2014. “Red is maybe red. It’s not the same if you hold an object under the sun as when you hold it in the shade.”

He sought to demonstrate this through artworks ranging from paintings and sculpture to light installations and architectural interventions, all characterised by their geometric abstraction and a vivid repetitive palette. In 1974 Cruz-Diez painted red, orange, green and black stripes across the walls and floor of the main terminal at Simón Bolívar International Airport in Caracas, a pattern he returned to in 2014 for a commission to decorate a boat, the Dazzle Ship, in the manner of camouflage in Liverpool’s dockyard as part of the city’s biennial. His experiments made him one of the leading figures in op art, the 1960s school interested in optical illusion, and kinetic art, which, around the same time, introduced movement, suggested or actual, into art.

For his Chromosaturation series, started in 1965, the artist would take over three successive galleries, bathing one in red light, a second in green, the third in blue. The intensity of the fluorescent bulbs changed the appearance of anything brought into these environments. As a visitor moved through the exhibition, the light of the previous chamber remained on the retina, further affecting perception. This was a natural progression from the Physichromie series that Cruz-Diez had started six years earlier. Here, the artist attached strips of wood painted in alternative colours at right-angles to the surface of a support. The dominant palette of wall-based work changed depending on the position of the viewer. Traditional painting, the artist wrote, merely represents “a memory”, whereas he hoped that with his work “what you see … is in the present”.

Born in Caracas, Carlos was the son of Carlos Cruz Lander and Mariana Diez de Cruz. His father, a chemist and amateur poet, encouraged his son’s interest in art. The younger Carlos enrolled at the city’s School of Fine Arts in 1940. There he became friends with Alejandro Otero and, when he joined three years later, Jesús Rafael Soto. They would become three of the best-known Venezuelan artists of the 20th century.

Having paid his way through college working as a graphic designer at Creole Petroleum, on graduation in 1945 Cruz-Diez took a position as a creative director at the McCann-Erickson advertising agency, the company sending him to New York in 1947 to study the latest industry developments. Nonetheless, despite this burgeoning new career, he continued to make art, contributing illustrations to El Nacional newspaper and having a solo exhibition the same year at the Instituto Venezolano-Americano in Caracas.

“When I left the School of Fine Arts I thought that art was intimately linked to society and the painter should be like a reporter – paint what was in front of [one’s] eyes; and what was before my eyes was misery,” Cruz-Diez recalled in 2018. “I placed myself to paint the misery I was witnessing, thinking that with a painting I could modify a social condition; I failed.”

A trip in 1955 to visit Soto in Paris, where his friend was included in Le Mouvement, a landmark survey of kinetic art at the Galerie Denise René in Paris, inspired a new direction. As the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez hardened in Venezuela, Cruz-Diez remained in Europe, moving to El Masnou, near Barcelona, where he had secured a teaching job at the art school. During his stay he showed Objetos Rítmicos Móviles at Galería Buchholz, interlocking manipulable wood sculptures laquered in different colours. After a brief return to Caracas in 1957, again to teach, this time typography, he left again for Europe in 1960, settling permanently in Paris.

While working on Physichromies, Cruz-Diaz also started a long-running series of geometric paintings titled Couleur Additive, in which the combination of two colours gave the illusion of a third. He was invited to be part of Bewogen Beweging (Moving Movement) at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, in 1961, his fellow exhibitors including Robert Rauschenberg and Jean Tinguely, and, in 1965, at The Responsive Eye at MoMA in New York, alongside Enrico Castellani, Ellsworth Kelly and his compatriot Gego. While the reviews were mixed, the American exhibition proved a huge visitor hit and is put forward as the first museum blockbuster. At the time, sniffily, Artforum noted that an “optical hysteria” had swept the gallery-going public.

Cruz-Diez shared the critics’ concerns. “The works in the show were turned into gadgets and the investigation behind them was trivialised,” he recalled in 2010. “This caused problems that lasted for years; kinetic art was erased from history.”

While the artist continued to practise graphic design on the side, producing catalogues for Rauschenberg and Jim Dine, as well as posters for Roy Lichtenstein, to coincide with their shows at the Sonnabend Gallery in Paris throughout the 60s, Denise René had started to sell his work, and Signals gallery in London marked a “decade” of the Physichromies (albeit four years early).

Cruz-Diez’s first public artwork was temporary, and consisted of 20 tinted-Plexiglass cubicles that occupied the pedestrianised Boulevard Saint-Germain in Paris for a street festival in 1969. The Caracas airport commission was followed by dozens more however, including a sculpture for the square outside the Venezuelan embassy in Paris, as well as interventions in the UBS headquarters in Zurich in 1975, a hydroelectric plant in Venezuela in 1977, a sculpture marking Andorra’s border with Spain in 1991 and the decoration of the paths leading to the Marlins baseball stadium in Miami in 2011.

The artist represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale in 1970 and, working from a converted belle-époque butcher’s shop in the ninth arrondissement, his children, and eventually, grandchildren assisting, he continued to exhibit regularly over the following decades. In his 80s, he brought a computer into the studio. In 2013 his 1989 book on colour theory, Reflections on Colour, was reprinted, as the participatory nature of Cruz-Diez’s work attracted a new generation of museum curators keen on eye-catching art that would pull in a wide public. A retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 2012 was followed by regular appearances in group exhibitions, including Light Show at the Hayward Gallery, London, in 2013, The Illusive Eye at El Museo del Barrio, New York in 2016 and Eye Attack at the Louisiana Museum, Copenhagen, in 2016.

In 1951 Cruz-Diez married Mirtha Delgado. She died in 2004, and a son, Jorge, died in 2017. He is survived by another son, Carlos, a daughter, Adriana, six grandchildren and a great-granddaughter.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion