It’s a Saturday in June and I’m running on time to meet Woody Harrelson, but one subway delay, one wrong turn, one mother with a double stroller failing to keep pace and clogging the already clogged sidewalks of midtown and I’ll be running behind. Adding to my anxiety: the possibility that I have no voice, not so much as a croak (laryngitis, a bad case). Brushing past a pair of doormen, I enter the lobby of a residential tower on the southwest tip of Central Park. I beeline for the elevator bank, press the up button, and glance at my phone. Two minutes after the hour. I’m now officially late. My pores open, sweat gushing out. At last, a muted ding as the doors slide apart. I board. To calm myself, I pull from my bag a sheaf of clippings on Woody. The big takeaway of recent years: He spent his entire adult life cuckoo for cannabis and then, in 2016, gave it up.

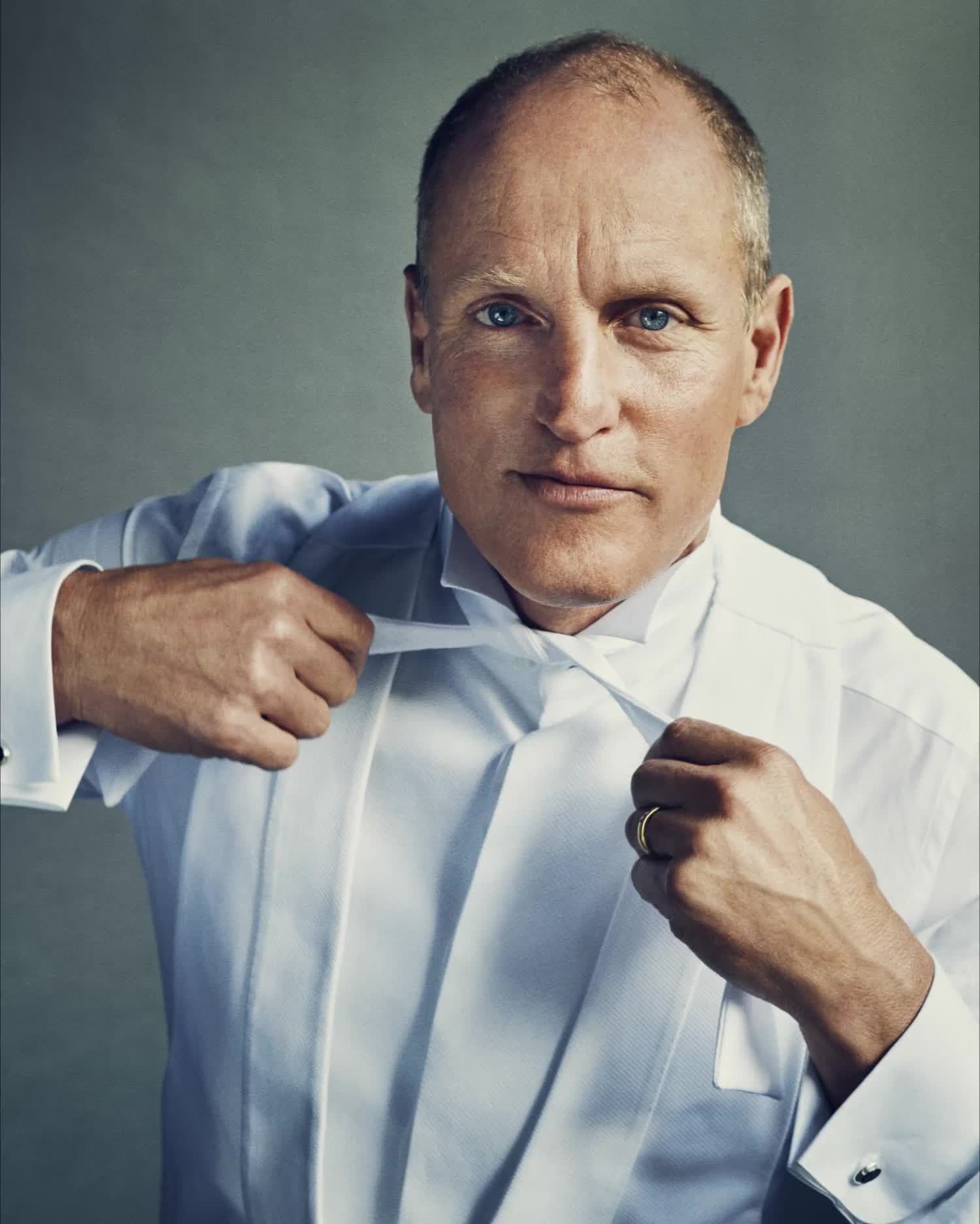

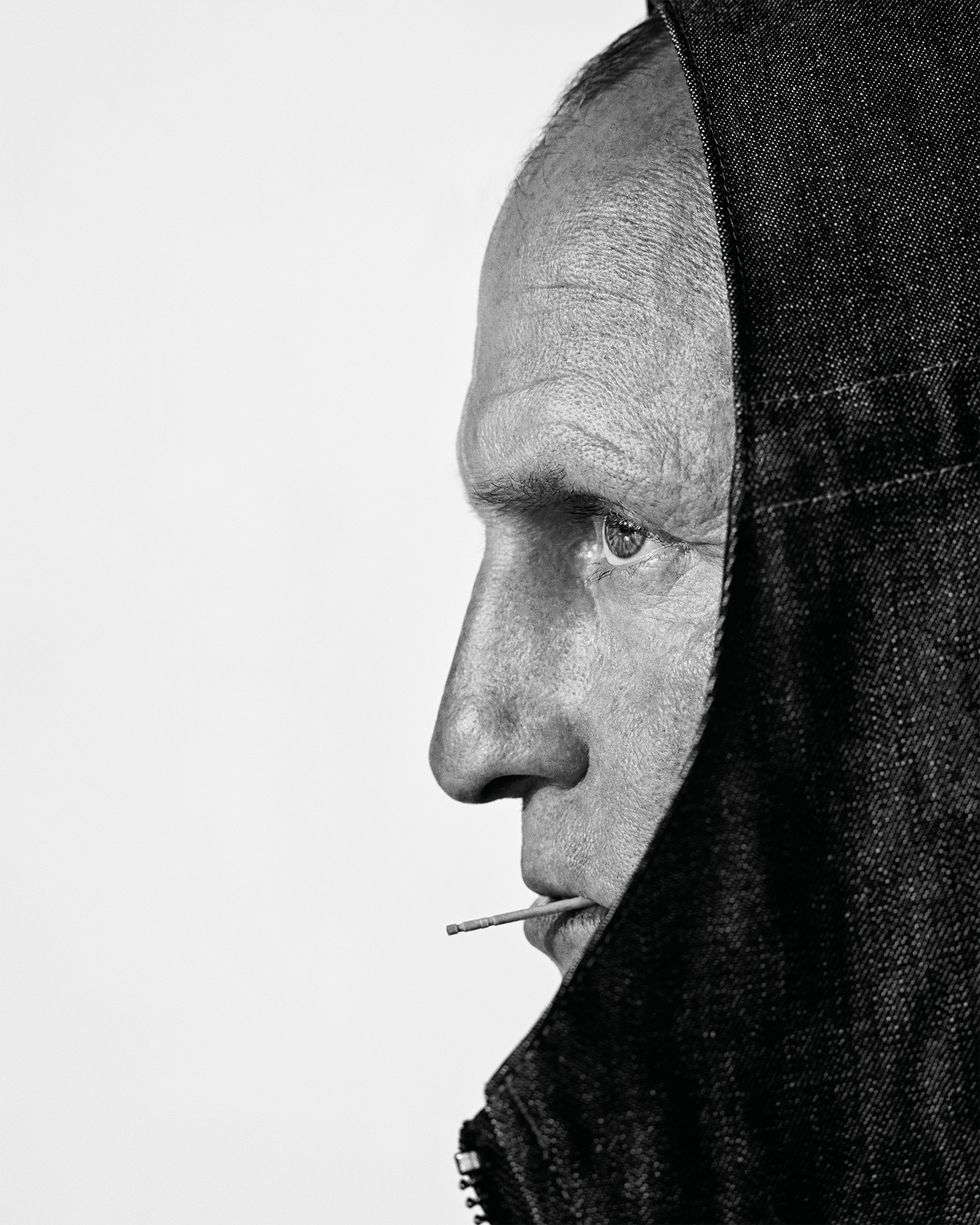

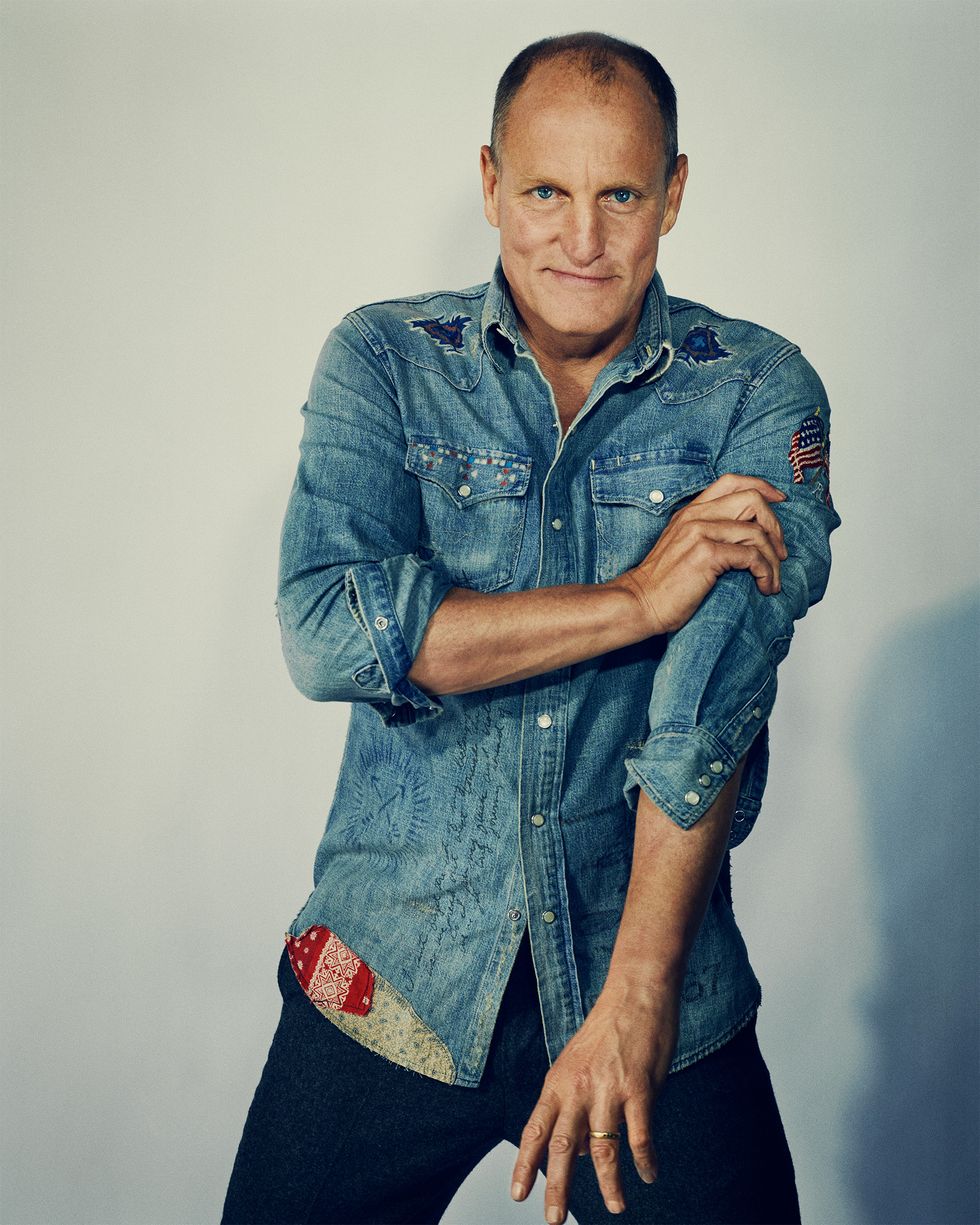

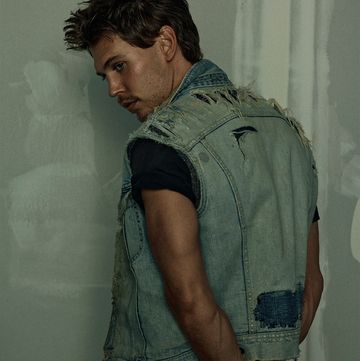

And yet, as I emerge from the elevator, I detect, if I’m not mistaken (and, frankly, I don’t see how I could be because it’s that strong), the sweet, feral stink of marijuana. Moments later, I’m standing at the entryway of the designated apartment, which doesn’t belong to Woody—he lives in Maui with his wife, Laura, and their three daughters, Deni, twenty-six; Zoe, twenty-two; and Makani, thirteen—but to a friend. I knock, and the door falls open as soon as my knuckles graze it. I take a tentative step inside. Then another. Then another. The smell is so strong now that it’s almost a taste. I take two more steps, and I’m at the edge of a large living room. In the center of it is Woody. Here’s what I see: a man of medium height, medium build, in a T-shirt and shorts. His hair is fair and mostly gone, and he keeps it short, the same length as the stubble on his jaw. His body is tight and muscular, yet he holds it in a loose and lithe way. His eyes are bright blue, and the whites, at this moment and for obvious reasons, are pale pink. He looks not just younger than his age, fifty-eight; he looks dramatically younger—early forties, tops.

Behind him is a table, long and wooden, atop which sit a bottle of mineral water; a manila envelope with the CAA insignia on it; the latest issue of Rolling Stone, the Weed Issue, of all issues, with, of all people, Willie Nelson, Grand Poobah of weed, on the cover, smoking, of all things, weed; two Ziploc baggies of weed; a Willie’s Reserve vape cartridge; rolling papers; a lone sock.

The silence stretches, becoming awkward. To break it, I say, “Hi.” My voice sounds like something scraped by a cheese grater and dropped to the bottom of a well. Woody hears it and his eyes go wide, and then he flashes that great Woody grin (gap-toothed, ear-to-ear) and lets out that great Woody giggle (half idiotic, half maniacal, all adorable) and in his great Woody drawl (languid- spacey, sexy-freaky, and purely stoned-sounding) says, “Whaaat? That is ridiculous.” And I nod because, yes, my voice is ridiculous. My voice is fucking absurd.

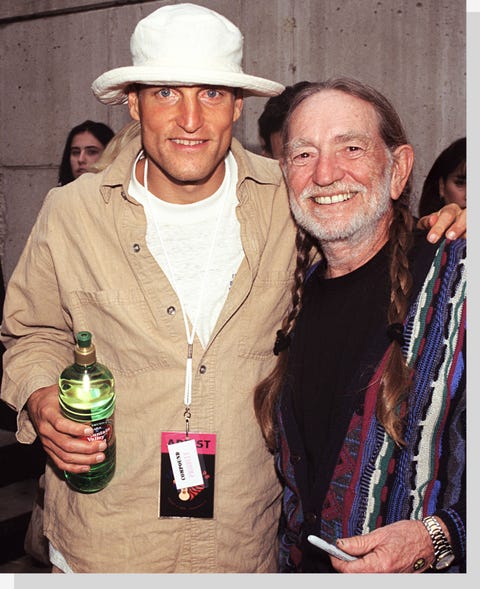

Woody picks up the Willie’s Reserve cartridge, asks if I smoke. I confess that I do not, and then add that I thought he didn’t either anymore. He takes a thoughtful pull on the cartridge. “Yep, I did quit,” he says on the exhale. “For almost two years. No smoking, no vaping. And then I ran into this guy”—he leans over and gives Rolling Stone Willie Nelson an affectionate chuck under the chin—“and that was that."

"See, everybody thinks of Willie as a model of progressive thinking and virtue, and he is, but he’s also got an evil side. Eee-vil. Now, Willie never felt too good about me quitting. And he kept trying to get me to not quit. We’d be playing poker and he’d pass me a vape pen, and I’d say, ‘Willie, man, I don’t do that anymore.’ And he’d act surprised, like it was news to him—every time, just as surprised as he could be. Then we were in Maui, and you know the whole reason I’m in Maui in the first place is Willie. Yeah, I went and saw one of his shows a number of years ago. I wanted to meet him. So afterward, I went to his bus and knocked on the door, and the door opened, and smoke was billowing out, and I look through the haze and I see this fellow with long hair holding a big old fatty, and he says, ‘Let’s burn one.’ And I know right away that he’s going to be a friend for life. He told me he had a place in Maui and to come on out, and that’s how I just sort of ended up there. Anyway, Willie passed me the pen after I’d won this huge pot. I was in a celebrating mood, so I snatched the pen from him and took a long draw. And Willie smiled at me and said, ‘Welcome home, son.’ ”

We both turn to the window, floor-to- ceiling, and goof on the view, panoramic.

“So what are you doing in town?” I finally say.

“I came to see a new play. Saw it last night, as a matter of fact. It’s called Happy Talk.”

“How was it?”

“Jesse Eisenberg wrote it, and that guy is just a genius.”

“Good actor, too. He’s your costar in Zombieland,” a 2009 zombie-apocalypse movie that was also a send-up of zombie-apocalypse movies, directed by Ruben Fleischer.

“That’s right,” Woody says.

“And your costar in the Zombieland sequel,” technically called Zombieland 2: Double Tap (in theaters October 18), directed once again by Ruben Fleischer.

“You got it.”

“And the Zombieland sequel is the whole point of this interview.”

A cloud passes over Woody’s sunny face. “Yeah, it is the whole point of this interview. But I’m not allowed to talk about it.”

“You’re not?”

“I mean, fuck it. I’ll talk about it with you. I’ll talk about it with you till the cows come home. It’s just, the studio people don’t want me giving anything away.”

“Ah, spoilers, et cetera.”

“I’ll tell you one thing about the movie, though, Lili. You’re going to love it. I don’t feel comfortable guaranteeing that to the masses, but I’ll guarantee it to you.”

That settled, Woody pats his flat stomach. “I’m hungry. Could you eat? How about a walk through the park and then lunch at Candle 79? It’s my favorite vegan restaurant in the world. We’ll get some coconut water for that voice of yours.”

“Great.”

“It’s a hike. Seventy-ninth and Lex.”

“Distance isn’t a problem.”

He looks doubtfully at my high heels. “You sure?”

I express confidence in the resiliency of my feet, though privately I’m as skeptical as he is.

He gives a que-será-será shrug, then claps twice. “All right. Let’s do it. I’ll be right back.”

I watch him vanish up a staircase I didn’t even know was there. I pull out a chair from the table, all ready to sit down, and that’s when I see it, the book splayed across the seat: American Spy, by E. Howard Hunt. Woody must’ve been reading it when I walked in.

Instantly, I’m in the middle of a full-blown grassy-knoll-oid panic attack, and it isn’t the contact high that put me there. Hunt was the ex–CIA agent who joined Nixon’s White House and then bungled the Watergate break-in. He was also rumored to have been the man behind JFK’s assassination. Several conspiracy theorists are convinced that he was the oldest of the three “tramps,” i.e., the trio of men arrested for vagrancy near the railroad tracks by the Texas School Book Depository on November 22, 1963. Those same conspiracy theorists are convinced that the tallest tramp was Charles Harrelson, Woody’s dad, a professional hitman and organized-crime figure who died in prison while serving a pair of consecutive life sentences for shooting a federal judge and who, during a subsequent standoff with police, jacked on cocaine and holding a gun on himself, confessed to murdering Kennedy. (All right, yes, so maybe I don’t think the Warren Commission played it straight with the American public. Maybe I don’t believe Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. Maybe I’ve spent some—okay, a lot of—time pursuing alternative explanations.) I deep-breathe my way to calmness just as Woody returns.

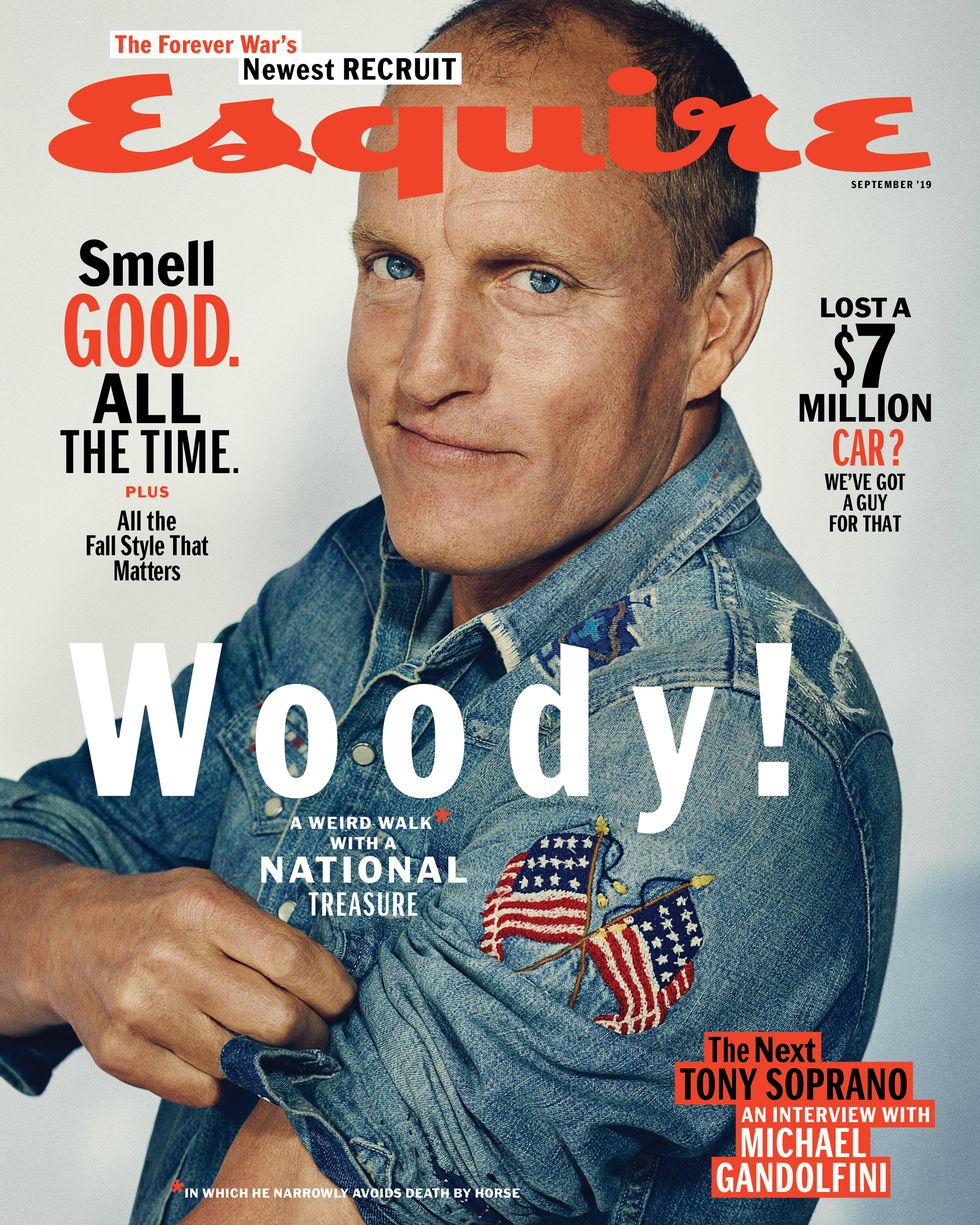

This article appears in the September 2019 issue of Esquire

Subscribe

He’s still in his T-shirt and shorts, though he’s added sandals, which appear to be made out of some all-natural, cruelty-free fabric and which shouldn’t work on anybody yet do on him, and a baseball hat with the words drugs and wine stitched above the brim. No one has ever looked less like the son of a gunned-up, mobbed-up, bad-hombre jailbird. Halfway out the door, he smacks his forehead and says, “Wallet, keys!” then trots back inside.

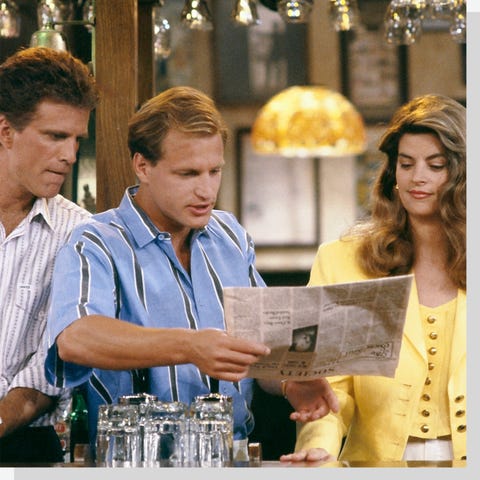

Together we exit the building and cross the street to Central Park. I’m a little worried about going out in public with him. It’s not just that he’s famous; it’s that he’s been famous for so long. His career began in 1985, when he joined the cast of Cheers as the bartender everybody wanted to share a cold one with, Woody Boyd. Woody (the character) was a sweet-natured, dim-witted country boy, and Woody (the person) inhabited him so easily and openly, without the faintest hint of coyness or condescension, that a viewer might be forgiven for thinking that Woody (the person) was also a sweet-natured, dim-witted country boy.

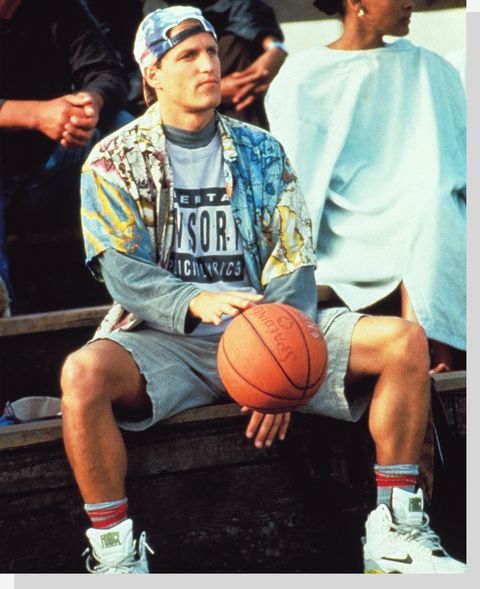

He wasn’t. He’d prove his smarts and his savvy by establishing himself as one of the most viable leading men of the nineties in movies in a range of styles and moods, from the hyperarticulate trash talk of White Men Can’t Jump (1992) to the erotic trance-out of Indecent Proposal (1993). He’d prove, too, his daring and his defiance when he risked that viability by playing ultra-unsavory, low-rent dudes possessed of a scary and scummy machismo, including the mass-murdering lover boy Mickey Knox in Natural Born Killers (1994) and the porn kingpin and scourge of the God-fearing Christian Right Larry Flynt in The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996). In recent years, Woody’s gravitated toward supporting roles in award-season prestige pictures such as Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017) and Emmy-bait TV shows such as True Detective (2014), as well as ka-ching franchises such as The Hunger Games and Star Wars. He often eclipses the nominal stars, not by upstaging or undercutting (he’s blessedly free of screen-hog impulses) but through sheer naturalness and sly, oh-you-rascal-you panache. He’s one of those actors who are easy to overlook or take for granted because they’re so good they don’t appear to be acting.

As we enter the park, I realize my worry about a crowd mobbing Woody was a needless one. He’s slipped on a pair of sunglasses. And those, along with the hat, make him virtually unrecognizable. He sets the pace, so we’re not motoring—my usual mode—but moseying, taking in the sights and sounds, our strides loose and loping. The day, I suddenly notice, is beautiful, absolutely primo. Not hot, warm, the sun still climbing in the hazy sky, soft rays reflecting off the spokes of bicycles and the carts of ice cream vendors. Around us, lolling on the grass, are carefree youth and cooing lovebirds, families with picnic baskets and soccer balls and Frisbees. I’d be in danger of entirely giving myself over to the pleasures of the day if not for Woody’s tendency to wander into oncoming traffic.

The first time I became aware of this little quirk was a few minutes ago, when we were moving from the south side of Fifty-ninth Street to the north side, and he stepped off the curb in spite of the do not walk sign flashing, and I grabbed him and yanked him back. If I’d been a beat slower, an Escalade would have flattened him. The second time is now. We are strolling along Center Drive, car-free, which should mean he’s perfectly safe, except it doesn’t because he won’t stay in the pedestrian lane, keeps drifting into the bike lane. A speeding pedicab comes within inches of him on his right, and I yank him again. Before I can dispel from my brain images of him lying in the road, his guts oozing like SpaghettiOs onto the pavement, and me, next to those guts, making an extremely awkward call to his publicist, a policewoman on an enormous white horse comes within inches of him on his left, and I yank him yet again. He gives me a curious look but seems otherwise unperturbed.

We stop to watch the commotion: the policewoman pulling over the pedicab driver; the pedicab driver trying to talk the policewoman out of writing a ticket; the policewoman writing a ticket; the horse smelling both their hair. Woody grins. “Hey, we just saw a crime go down.”

I decide now would be a good time to ask him about his childhood. (I’m not a Freudian, but I’m not not a Freudian.) The basics: Born in Midland, Texas, in 1961. His father abandoned the family when Woody was seven, right around the time he started acting out at school. His mother, Diane—maiden name Oswald, no known relation to Lee Harvey, yet I attach mystical significance to this coincidence anyway, just can’t help myself—a devoutly religious legal secretary, moved Woody and his two brothers to her hometown of Lebanon, Ohio, when he was twelve.

To get the ball rolling, I say, “You were a troubled kid?”

“Yeah, that would be an accurate statement, I suppose. Though I was a mama’s boy, too.”

We’re walking again, and there is, I realize, no graceful way to record the conversation, so I just stick my phone under his chin, try to catch the words falling out of his mouth.

He continues: “I had a lot of anger, a lot of rage. To get kicked out of nursery school, you’ve got to go some distance. And then I also got kicked out of first grade. They thought I stole a purse, but I didn’t, and a teacher beat me up for stealing a purse I didn’t steal. So I went around the school breaking windows with my bare fists. After that, I had the blessing of going to Briarwood,” a private school in Houston catering to children with special needs. “The idea there was to educate and simultaneously give love to the child, which sounds hokey, but it worked. I’d do something that was wrong or violent, and they’d treat me with love.”

“Was the relocation to the Midwest difficult for you?” I ask.

“No, it was good. I wasn’t an outcast anymore. I remember my mother saying, ‘Your teacher told me you’re quite popular with the other children.’ I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew she was proud of me.”

“When did you become interested in acting?”

“I was in my first play my junior year of high school. The closest thing I’d done to acting before that was an Elvis impression for the guys on the football team. I’d do ‘All Shook Up.’ The play was for my church. Actually, it wasn’t really a play. What do you call that time in Bethlehem—you know, like, in the manger?”

“The nativity scene?”

“That’s right. But funny. I played a drunk. I had this great entrance where I came in from the back and stumbled between the pews and landed in the lap of my great-grandmother Polly.”

He’s describing Polly’s reaction when I spot a fork in the road. “I think if we go right here, we’ll come out on Seventy-second and Fifth,” I say. “That’s the turn we want.”

“Nah, nah, we got a little ways more to go.”

“Are you sure? Because my gynecologist is on Seventy-fifth and Fifth, and the cab driver always—”

“Nope, we’ve got to keep going.”

I shrug, keep going. “Let’s get into your college years,” I say. “You went to Hanover College, in Indiana?”

“On a Presbyterian scholarship. I majored in English and theater. I almost minored in theology, because I was considering going into the ministry.”

“And then, I guess, you reconsidered?”

“That I did.” He chuckles. “You know, Mike Pence was there at the same time.”

I almost drop my phone. “You’re kidding me.”

“As a freshman, I gave a sermon to a youth group, and Mike was the guy running the show. He was a junior, I think.”

“What did you make of him?”

“He struck me as a nice guy, very sincere. I don’t know how well we’d get along now, but we got along okay then.”

I spend more time probing this Mike Pence connection because—well, because it fascinates me. Two sides of the American male archetype: The hedonist versus the holy roller; the profane versus the sacred; Hollywood’s wildest wild child, a raw-foodist and eco-crusader and Iraq-war protester and marijuana-legalization champion, versus the prim and proper vice-president of the United States, a man who calls his wife Mother and who is triggered by the 1998 animated Disney feature Mulan, briefly intersecting at a small college in a sleepy town in the middle of the country. It’s one of those crazy accidents of geography and history, and it’s enough to make you believe not only in a higher power but in a higher power with a sense of irony.

I raise my head and glimpse, through the foliage, a street sign. I point it out to Woody. “Eighty-eighth Street?” he says, removing his hat, wiping the sweat from his brow. “That is a serious overshoot.”

“I don’t think there’s another exit for a while, so we should probably go back to the last one.”

“Not necessary. I can fix this.” He turns, starts tramping through the small wooded area between the paved path and the wall that divides Central Park from the city proper. He mounts the waist-high wall. “All we got to do is climb over this thing,” he shouts, and then disappears over the edge.

I run after him, sidestepping tree roots and underbrush. When I reach the wall, I look down. There he is, beaming up at me from the sidewalk. “Yeah,” I say. “I don’t think so.” “It’s not so far.”

The drop is eight feet, minimum. Trying to keep my tone un-freaked-out, I say, “I think you’re failing to factor in my heels.”

“So take ’em off.”

This I cannot, must not, do. I developed blisters about twenty minutes ago; those blisters popped about ten minutes ago. At present, my feet and shoes are fused together. Their separation would mean blood, lots of it.

“Come on,” he says. “It’s easy.”

I make a few quick calculations. If I retreat, attempt to find an official point of egress, and return to this spot, a quarter of an hour will have passed. In that time, Woody might get lost or get himself killed. (The cars on Fifth Avenue move fast.) At the very least, our conversational rhythm will have been broken. The moment has come for me to, in the words of Tallahassee, the character Woody plays in Zombieland, “nut up or shut up.” I clamber to the top of the wall and throw my legs over it. I hang there for several seconds, my sole consolation being that my skirt is formfitting, which lessens the possibility of my flashing the entire Upper East Side. I close my eyes, hold my breath, let go.

Miracle of miracles, I land on my feet. Woody applauds.

We make it to the restaurant alive. Woody did have a few more close calls en route. (A Mercedes honked at him after he stepped in front of it at the median strip on Park Avenue, and he backed up, muttering, “Okay, okay, why’s everybody so serious?”) But somewhere between Eighty-fourth Street and Eightieth, I realized that vigilance was not required of me in this situation because he was in no need of saving. His relationship to danger is roughly equivalent to Wile E. Coyote’s relationship to gravity: If Wile E. walks off a cliff, he’ll remain suspended in the air until he recognizes the dire nature of his predicament, at which point he’ll plummet. Woody does Wile E. one better. He never recognizes that he’s in danger, and that’s why he never is. Danger can’t touch him.

Over black bean–pumpkin seed burgers and bread-crumb-crusted cauliflower, Woody discusses his career regrets (“I was offered—what’s the ‘Show me the money’ movie? Jerry Maguire? I was offered Jerry Maguire, and I said to Jim [James L. Brooks, one of the film’s producers], ‘Nobody is going to give a shit about an agent’ ”); his initial impression of Zombieland (“My agent sent me the script, and I said, ‘Zombies, dude? Really? Has it come to this?’ And he said, ‘Will you please just read it?’ Finally, I did, and I’m like, ‘Damn. That’s good writing’ ”); and his possible homecoming (“I kind of love the idea of moving back to Texas, maybe Austin, maybe over by Matthew [McConaughey] or up by Willie”). After the waiter clears the dessert plates—chocolate–peanut butter bliss, a double order—Woody pulls out his Ziploc bag and his papers and, cool as you please, begins rolling a joint. As soon as he lights it, a small, dark-haired woman hurries over to the table, and I’m certain she’s going to tell him to put it out, but she doesn’t. Instead, she wraps him up in a bear hug. It’s Joy Pierson, a co-owner of Candle 79. I half listen as she and Woody catch up—exchange restaurant gossip, gossip gossip, casually bitch about Trump. And then Joy mentions a dinner Woody had with him. I feel my ear tilt like a cup waiting to be filled. Before it can receive another drop, Joy gets called to the kitchen. I ask Woody to explain.

He gives a heavy-lidded nod. “You want to hear about that dinner? Sure, I’ll tell you about that dinner. So Jesse Ventura [former pro wrestler and ex-governor of Minnesota] is a buddy of mine, and he called me up—and this is in, oh, 2002—and said, ‘Donald Trump is going to try to convince me to be his running mate for the Democratic ticket in 2004. Will you be my date?’ I said, ‘Yeah, man.’ So we all met at Trump Tower, sat down. Melania was there, only she wasn’t his wife yet. And it was, let me tell you, a brutal dinner. Two and a half hours. The fun part was watching Jesse’s moves. It would look like Trump had him pinned, was going to get him to say yes, and then Jesse would slip out at the last second. Now, at a fair table with four people, each person is entitled to 25 percent of the conversation, right? I’d say Melania got about 0.1 percent, maybe. I got about 1 percent. And the governor, Jesse, he got about 3 percent. Trump took the rest. It got so bad I had to go outside and burn one before returning to the monologue monopoly. Listen, I came up through Hollywood, so I’ve seen narcissists. This guy was beyond. It blew my mind. He did say one thing that was interesting, though. He said, ‘You know, I’m worth four billion dollars,’ or maybe he said five billion dollars—one of those numbers, I forget. Anyway, he said, ‘I’m worth however- many billion dollars. But when I die, no matter how much it is, I know my kids are going to fight over it.’ That was the one true statement he made that night, and I thought, Okay, yeah, that’s pretty cool.”

Lunch ends around dinnertime. Woody and I wander outside. The traffic is close but sounds distant, like the buzzing of bees, and in the air is the drowsy scent of spilled diesel. Woody suggests going back the way we came, another walk through the park. I admit the sad truth about my feet. He laughs and hails a taxi.

I drop him off at Columbus Circle and continue downtown. Yes, there was more Willie’s Reserve in the cab, and, yes, the windows were sealed, and, yes, I’m once again secondhand high. But that’s not why I’m relaxed to the point of stupor, out of it in the pleasantest of ways. Unh-uh. It’s firsthand Woody—the vapors he gives off—that’s got me feeling so fine.