Bereaved people should "move on" from grieving the loss of a loved one, right? Scholarly publications call this idea misguided, a myth. However, many people must still believe it - and say it in private conversations - because I have read countless articles and blogs expressing anger and pain around it. In a raw and eloquent Facebook post, Kay Warren addresses the suggestion that she and her husband should be moving on from the loss of their son Matthew, who died of suicide. "The truest friends...[are] willing to accept that things are different," she writes. "They're ok with messy and slow and few answers....and they never say 'Move on.'"

To me, this "moving on" concept makes no sense at all. In fact, my brother - who died just over two years ago - is the person I least want to move on from, because he is the most gone.

Where did it come from, the idea that one should completely separate from a loved one who has died? How is it still in our collective consciousness, given that it works for absolutely no bereaved person I know? Why do I not see it written down in advice articles? Perhaps something instinctively feels wrong about advising people to move on - wrong enough that we don't offer it as written advice, but entrenched enough that we still find ourselves saying it.

I think it feels wrong because it is impossible.

In recent years, research has revealed information about how our relatives and close friends, our life experiences, and our traumas change us physically and psychologically. Mothers and children exchange cells during pregnancy and at birth, cells that may remain in the other person's body and play a role in health down the road. Stress and trauma can permanently change DNA in the cells of the traumatized person, in such a way that the altered DNA is heritable, often resulting in children who are more likely to experience stress-related psychiatric disorders. In education, carefully designed short-term interventions can lead to radical shifts in attitude and behavior that change how students think and work.

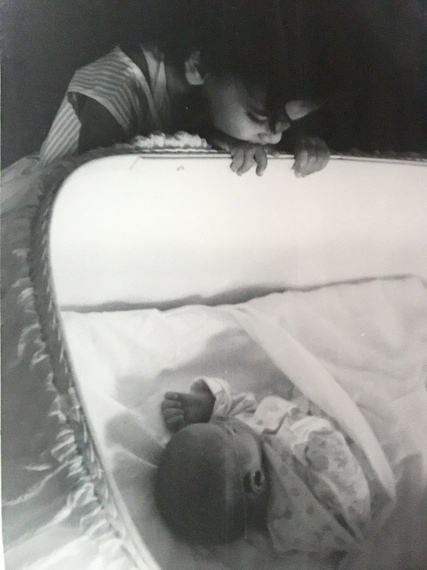

Our lives change us, often permanently. People and experiences become part of us at a cellular level. How, then, are we to be expected to "move on" from a child, a life partner, a sibling, a close friend, a parent who has died? How could I set aside the parts of myself linked to my brother? You might as well ask me to cut my own heart out with a knife, leave it by the curb, and then continue walking down the road. It is impossible.

What, then, is possible? For me, it's noticing the thoughts and emotions that come up from moment to moment and sitting with them however I can. What that looks like changes all the time. I talk about him, or I stop talking. I cry in my car, or I go running. I pore through old photo albums, or I put all the albums away. I notice when his favorite songs come up on my shuffle, I write about memories, I text his friends, I take walks alone, I escape in work, I wallow in old e-mails. I show up, day after day, and I try to understand.

Caregivers who study the process of grieving refer to integrated grief - an enduring state of grief in which the loss, your understanding of it, and your emotions around it become incorporated into your life over time. Integrated grief doesn't mean forgetting the person or setting aside the pain. On the contrary, it sustains the bond by including both the agony of loss and the positive memories. I believe this is what I am instinctually doing - trying to integrate my grief. As I slowly realize I cannot be connected to my brother how I once was, I am creating a whole new web of connection between us - a web that needs all the threads, good, bad, and ugly, to stay strong.

I have family and friends whom I love and care for, multiple work responsibilities, and personal and professional aspirations for the future. I want and need to be able to continue. So, yes, I move on - not from, but with my brother. Moving on with him gives me a chance to live.

Subscribe to Life Without Judgment to receive writings by Sarah Lyman Kravits in your inbox.