How Electronic Voting Could Undermine the Election

As foreign hackers target election data, voters may lose faith in digital ballots.

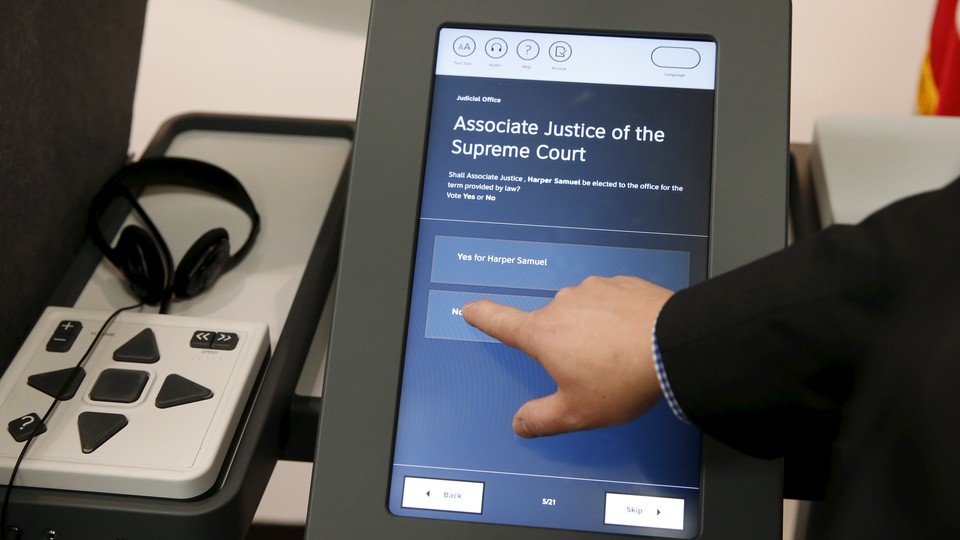

It's 2016: What possible reason is there to vote on paper? When we use touchscreens to communicate, work, and shop, why can't we use similar technology to vote?

A handful of states, and many precincts in other states, have already made the switch to voting systems that are fully digital, leaving no paper trail at all. But this is despite the fact that computer-security experts think electronic voting is a very, very bad idea.

For years, security researchers and academics have urged election officials to hold off on adopting electronic voting systems, worrying that they’re not nearly secure enough to reliably carry out their vital role in American democracy. Their claims have been backed up by repeated demonstrations of the systems’ fragility: When the District of Columbia tested an electronic voting system in 2010, a professor from the University of Michigan and his graduate students took it over from more than 500 miles away to show its weaknesses; with actual physical access to a voting machine, the same professor—Alex Halderman—swapped out its internals, turning it into a Pac Man console. Halderman showed that a hacker who has access to a machine before election day could modify its programming—and he did so without even leaving a mark on the machine’s tamper-evident seals.

But it wouldn’t even take a full-fledged cyberattack on an electronic voting system to throw a wrench in a national election. Even the specter of the possibility that the American electoral system is anything but trustworthy provides ammunition to skeptics to call foul if an election doesn’t go their way.

That’s the argument that Dan Wallach, a computer-science professor at Rice University, put forward in an essay earlier this month titled “Election Security as a National Security Issue.” Nicholas Weaver, a professor and security researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, expanded on Wallach’s thesis in Lawfare this month. “Voting systems need to convince rational losers that they lost fairly,” Weaver wrote. “In order to do that, it is critical to both limit fraud and have the result be easily explained.”

Paper ballots are harder to fudge than votes stored in bits and bytes: A manual recount can help assuage fears of a rigged election. Even voting machines that spit out a voters’ choices on a piece of paper before submitting them are verifiable. But machines that record votes directly without providing a physical receipt aren’t terribly easy to audit if accusations of fraud begin to fly.

The more that voters’ faith in electronic systems is shaken before November, the higher the likelihood that voters might question the outcome of an election that includes electronic ballots. Donald Trump has already made repeated predictions that the general election will be “rigged,” even going so far as to recruit volunteer “Trump Election Observers” to monitor polls. And election-related security issues may already be on voters’ minds after two email hacks this summer, one that targeted the Democratic National Committee, and another that targeted the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.

Now, it appears that foreign hackers recently made their way into two state voter databases. In response, the FBI quietly sent out an alert earlier this month warning officials to improve the security of their election technology, Yahoo News reported Monday, the same week that Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson offered state officials federal help in shoring up election-related cyberdefenses.

The states aren’t identified in the FBI alert, but Yahoo News reports that they’re likely Arizona and Illinois, two states that struggled with voting security earlier this summer. In Illinois, hackers appear to have made off with the voter-registration information of about as many as 200,000 voters; in Arizona, attackers don’t appear to have stolen any data.

Spying on voter-registration data isn’t the same thing as manipulating election results, of course. Most of the information in voter rolls is publicly available, even if cumbersome to assemble, or is available from data brokers for a cost. But the attacks in Arizona and Illinois suggest that foreign hackers are targeting election data—and raise the prospect that they may also try to manipulate votes come November.

Wallach, who says he was invited to testify about voting security before the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee next month, says the attacks on the state election data heighten the urgency for states to adjust their approach to voting before November.

Weaver went further. “This is yet more ammunition in the contention that pure electronic voting is simply too dangerous: We must use paper, either directly filled out by the voter or as a voter verifiable paper audit trail,” he wrote in an email.

“Especially with the problem of the ‘irrational loser’: Trump can point to this and go ‘See, the system is rigged,’ and I personally worry that such language might inspire some fraction of his followers to commit a violent act.”