Hong Kong-raised Filipinos on their struggle for identity, discrimination, and feeling stuck between two cultures

Unfamiliar with their nation’s heritage yet often unable to speak Cantonese fluently, they grew up being told their future lay at home, but live and work in Hong Kong; it’s left some feeling not completely Filipino or Hongkonger

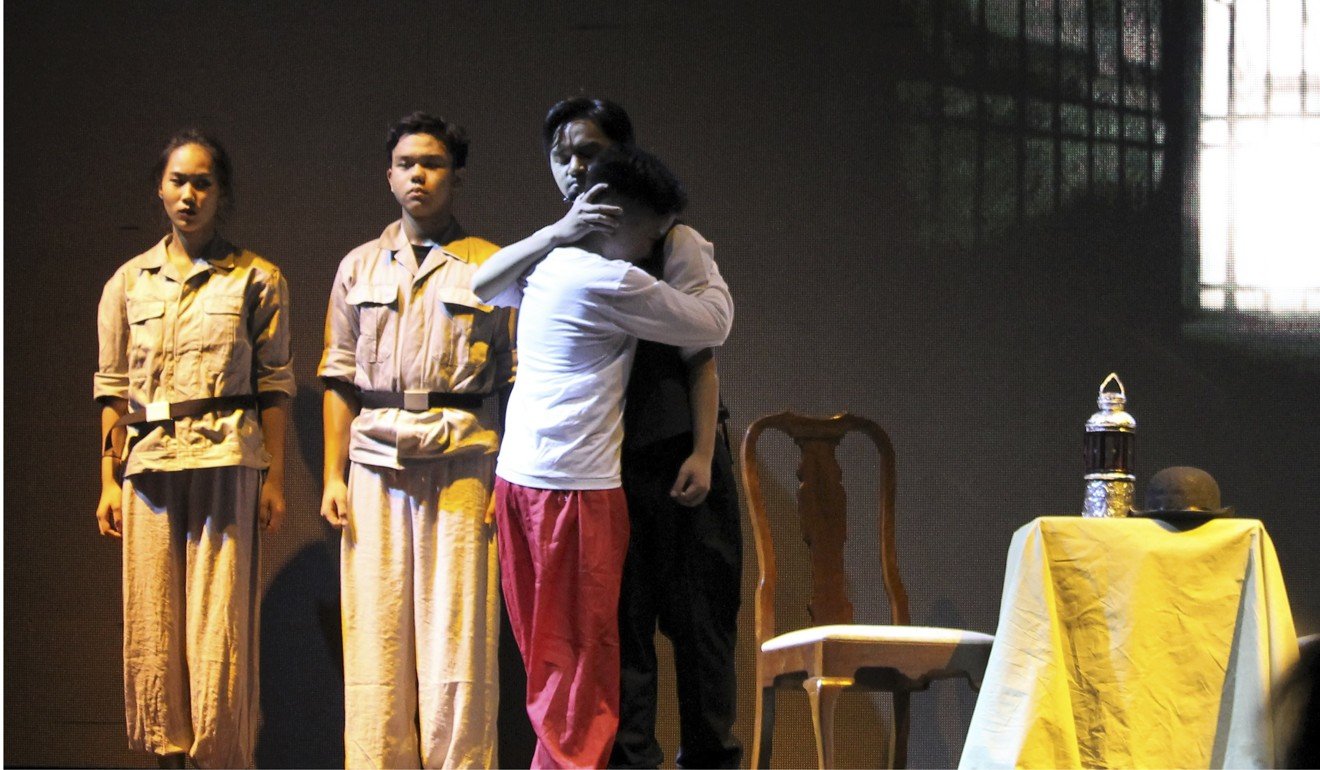

Zandru Justin Sabinano, a 17-year-old Filipino born and raised in Hong Kong, admits he had barely heard of one of the Philippines’ greatest historical heroes when he was asked to play the role of José Rizal in a recent theatre production.

“Rizal was quite foreign to me, but for my role I did a lot of research to learn more about him,” Zandru says.

The song and dance musical, Ang Ugoy ng Duyan (The Sway of the Cradle), was organised by the Philippine consulate and the International Social Service Hong Kong Branch, and held at MacPherson Stadium in Mong Kok to an audience of about 200.

Filipino son of Hong Kong domestic worker touches hearts with tribute to her 20 years of hard labour

Filipino residents aged five to 29 played roles in the tale of a fictional teenager called Barry – who was born in Manila but grew up in Hong Kong – who goes back to his hometown for the first time in many years. His family educates him about Philippine festivals, cultural traditions and food, and he also learns about Rizal – who died a martyr in 1896, around the end of Spanish colonial rule of the Philippines.

Zandru is typical of many young local Filipinos who have spent most or all of their lives in Hong Kong and know little of their heritage. The Mong Kok event was in part aimed at strengthening their Filipino identity and encouraging them to take more interest in Philippine culture.

Immigration statistics show there were 16,675 Filipino residents in Hong Kong as of June this year, a figure that excludes 195,948 domestic workers from the Philippines.

Although Zandru likes living in Hong Kong, he says the downside is the discrimination he occasionally faces.

“People here assume if you are Filipino you must be a domestic helper,” says Zandru, whose mother is a money lender and father is a bartender in Lan Kwai Fong.

He admits he sometimes has a hard time in Hong Kong because he doesn’t speak much Cantonese, and found the going tough attending a local school.

“I was rebellious at the time. I thought I only needed English, but now I’m struggling to learn Cantonese,” he says. “I would sleep or talk during Chinese class and not pay attention. The only one to blame is myself.”

Kristeen Romero, another Filipino born and raised in Hong Kong, had a similar experience. The 23-year old’s parents had good jobs in Hong Kong – her mother worked at toy company Mattel as a project manager, her father in sales – but they had always expected to one day return to the Philippines as there were frequent layoffs at Mattel.

With the idea being drummed into her head that her stay in the city was temporary, Romero didn’t take learning Cantonese seriously, and admits she thought the language was inferior to English.

“Most ethnic minority kids study at Delia [Group of Schools] but they don’t teach us how to read or write Cantonese,” Romero says with a tinge of frustration.

Despite the language barrier, Romero thinks Hong Kong is a better place for her to be than the Philippines because the local education system is widely respected.

“My older sister studied in the Philippines, and I went through HKCEE [Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examination] and was in the last batch of students to study Hong Kong A-levels,” she explains. She says her sister returned to Hong Kong after graduating but, like many of her generation, ended up working in the food and beverage industry.

Although Romero returned to the Philippines every summer until she was 16 and can speak Tagalog, the national language, she says there is a lot of slang or linguistic context she is unfamiliar with. Although her relatives understand her situation, Romero feels classmates at university in the Philippines would not be so kind.

We struggle for identity, like third-culture kids. Everything here is in Chinese, and at home we speak Tagalog and English, and our parents think we will end up in the Philippines

Romero, though, is pleased with her accomplishments: she graduated from a private college in Hong Kong after school and now works in digital marketing for a start-up in Tsim Sha Tsui.

Roland Joseph “RJ” Sonsing, 36, came to Hong Kong from Manila at the age of five. His parents had originally arrived in the early 1970s, with his father taking a job as a nightclub musician and his mother becoming a quality control engineer for a tobacco company.

Like Romero, Sonsing studied at Delia Group of Schools, but he then went back to the Philippines for college. There, he discovered his love of cooking. With a wife and young daughter, he moved back to Hong Kong in 2005 because he expected to have better career prospects.

After four years working in a series of positions, he got a job at Paisano’s pizza restaurant. He rose from toiling in the kitchen to general manager and executive chef within five years. “I helped the company grow from one to six branches,” he says.

In 2013, with four children to feed, he struck out on his own with Checkmate Pizza – which sells super large pizzas. He now has outlets in Kennedy Town and Hung Hom.

Sonsing considers himself fortunate among local Filipino residents in that he made an effort to learn Cantonese when he was young, although he still considers himself Filipino even after living in Hong Kong for 30 years.

“I experience racism … [as] I’m not Chinese, which made me more determined to open my own business,” he says. “There are Filipino managers, waiters and bartenders who are too scared to open their own place, saying they don’t want to take the risk … I say, if you know what you’re doing, why not take the risk?”

Meet the ethnic minorities breaking through Hong Kong’s race barrier

Although three of his four children were born in Hong Kong, they live in Manila with his wife because of the high cost of raising a family in Hong Kong. More importantly, he wants them to be culturally attuned to their homeland.

“They speak English and Tagalog, but I want them to study in the Philippines and learn Filipino culture. I didn’t – I only know basic Tagalog and didn’t know about the history, and was very embarrassed about it.”

Sonsing’s friend, Ryan Enriquez, came to Hong Kong in 1995 at the age of 16, five years after his parents settled here. His father is a drummer and his mother a waitress.

“There were seven of us – my four brothers and I, and my parents – living in a small bedroom with two other families in a three-bedroom flat in Jordan,” he says, recalling the constant wait for the bathroom.

Two years later his Hong Kong-born Filipino girlfriend became pregnant; they quickly tied the knot and he focused on supporting his family. This meant quitting computer courses and getting a job clearing tables at the now-defunct Planet Hollywood restaurant. He later became an assistant manager in restaurants and discos.

In 2005, Enriquez was diagnosed with leukaemia. Rounds of chemotherapy and a stem-cell transplant from his younger brother helped him pull through, and he has now been cancer-free for three years.

“If we were in the Philippines, we would have to sell everything to pay the medical bills, but because we are Hong Kong permanent residents, 20 to 30 per cent of the cost is covered,” he says.

Despite being already in his teens when he came to Hong Kong, Enriquez says he feels “like a tourist” back home. Nevertheless, he would still like to retire in the Philippines, probably in the countryside where the environment is less polluted.

‘I was forced to sell my body in a Hong Kong bar’: a Filipino’s experience of trafficking, prostitution

Enriquez says he has never experienced discrimination in Hong Kong and is grateful he has been able to overcome the immense obstacles he has faced. “I want my kids to know that life is full of challenges,” he says.

Such obstacles need not be faced alone. In 2013, a community support group called Section Juan was formed to give young Filipinos in Hong Kong the tools and encouragement to aspire to better lives. It is one of several Filipino support groups active in Hong Kong.

“They are trying to help with the [sort of] problems that I went through,” Romero says.

Romero adds that volunteering with the group, which organises activities and dispenses advice on how to apply for tertiary education, has helped her come to terms with her own past.

“We struggle for identity, like third-culture kids. Everything here is in Chinese, and at home we speak Tagalog and English, and our parents think we will end up in the Philippines,” she says. “But we don’t feel completely Filipino or Hongkonger. It took me a long time to figure out it was OK to be both.”