The Fight to Decolonize the Museum

Textbooks can be revised, but historic sites, monuments, and collections that memorialize ugly pasts aren’t so easily changed. Lessons from the struggle to update the Royal Museum for Central Africa, outside Brussels.

One of Europe’s loveliest urban journeys begins as you step aboard a trolley at the Montgomery Metro station in Brussels. Its tracks quickly emerge from underground to travel along a grand, tree-shaded boulevard lined with elegant mansions a century old or more, many of them now embassies. Then the route leaves the street traffic behind to run through a leafy forest of beech and oak, a former hunting ground for the dukes of Brabant that becomes a symphony of fluttering green light on a spring day. Finally the tracks end near a palatial stone edifice whose very existence embodies some of the unresolved tensions of our globalized world.

Welcome to the Royal Museum for Central Africa. Although one of the largest museums anywhere devoted exclusively to Africa, it is thousands of miles from the continent itself. The tall windows, pillared facade, rooftop balustrade, and 90-foot-high rotunda of the main building give it the look of a chateau. That impression is only enhanced by an inner courtyard and a surrounding park: formal French gardens, a reflecting pool and fountain, ponds with ducks and geese, wide lawns laced with hedges, and carefully groomed paths that sweep away to majestic trees in the distance.

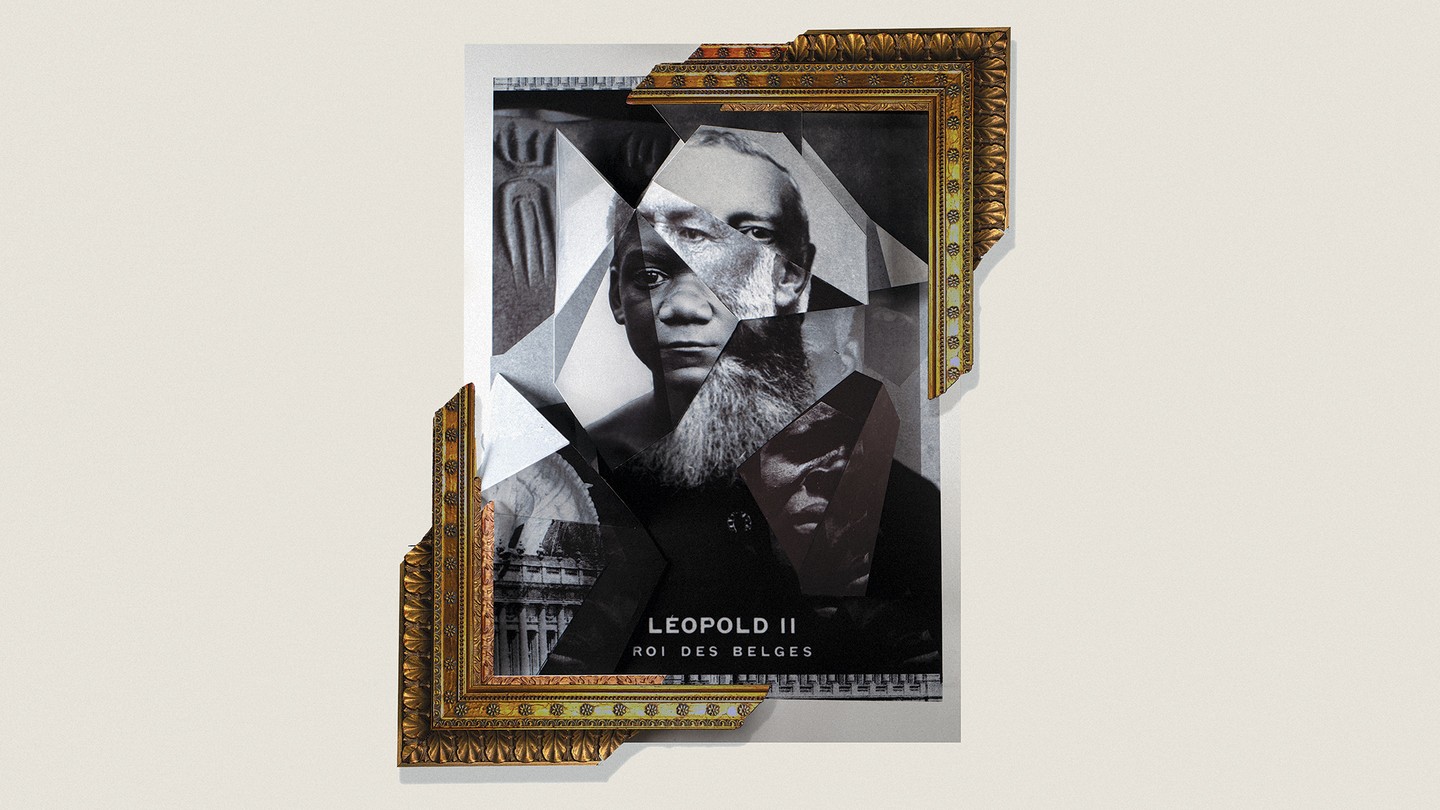

A visitor here is a long way from Africa, but not from the fruits of the continent’s colonization. For 23 years starting in 1885, Belgium’s King Leopold II was the “proprietor,” as he called himself, of the misnamed Congo Free State, the territory that today is the Democratic Republic of Congo. Exasperated by the declining power of European monarchs, Leopold wanted a place where he could reign supreme, unencumbered by voters or a parliament, and in the Congo he got it. He made a fortune from his privately owned colony—well over $1.1 billion in today’s dollars—chiefly by enslaving much of its male population as laborers to tap wild rubber vines. The king’s soldiers would march into village after village and hold the women hostage, in order to force the men to go deep into the rain forest for weeks at a time to gather wild rubber. Hunting, fishing, and the cultivation of crops were all disrupted, and the army seized much of what food was left. The birth rate plummeted and, weakened by hunger, people succumbed to diseases they might otherwise have survived. Demographers estimate that the Congo’s population may have been slashed by as much as half, or some 10 million people.

Using testimony and photographs from missionaries and whistle-blowers, the British journalist Edmund Dene Morel turned Leopold’s slave-labor system into an international scandal. Luminaries from Booker T. Washington to Mark Twain to the archbishop of Canterbury took part in mass protest meetings. Rising outrage finally pressured the king to reluctantly sell the Congo to Belgium in 1908, a year before his death.

Until that point, Leopold, a master of public relations, had worked hard to portray himself as a philanthropist, motivated only by the desire to bring Christianity and civilization to the “Dark Continent.” In 1904, he had hired his favorite architect, the Frenchman Charles Girault, who designed the Petit Palais in Paris, to build this museum on the site of a royal PR coup seven years earlier. In 1897, when a world’s fair took place in Brussels, the king had orchestrated a special exhibit on the Congo here, just outside the city. Its centerpiece was human beings: 267 Congolese men, women, and children who for several months were on display in three specially constructed villages with thatched roofs. In the “river village” and the “forest village” they used drums, tools, and cooking pots brought from home, and paddled dugout canoes around a pond. In the “civilized village,” men dressed in the uniform of Leopold’s private Congo army played in a military band. More than 1 million visitors came to see them.

In 1910, soon after the king died and his personal colony became the Belgian Congo, the museum finally opened its doors. Part of it houses archives and sponsors natural-science research, but throughout the 20th century, its public exhibition halls continued to express a highly colonial view of the world. The human zoo was gone, but silence about the plunder remained. When I first visited the museum, in 1995, the exhibits of Congo flora included a cross section of rubber vine—but not a word about the millions of Congolese who died as a result of the slave-labor system established to harvest that rubber. It was as if a museum of Jewish life in Berlin made no reference to the Holocaust.

After I mentioned my visit in King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, published a few years later, a dissident staff member began emailing me about internal conflicts. The museum remained filled with relics of colonial soldiers and explorers and larger-than-life statues of heroic, idealized figures with inscriptions like “Belgium Brings Civilization to the Congo.” Belgians who cared about human rights were demanding changes; the country’s powerful “old colonial” lobby—people who had lived and worked in the Congo before it became independent, in 1960, and their descendants—was resisting them.

The institution was paralyzed. Finally, in 2005, with much fanfare, a temporary exhibit purported to tell the truth about colonialism at last. It contained a few small photographs that showed the violence of colonial rule—but not a single display case explained the slave-labor system. The exhibit was so evasive that an activist group in Brussels published an online guide in the country’s two main languages, French and Dutch, that visitors could print out and take to the museum. It provided text and photographs—of women hostages in chains, for example, and enslaved laborers carrying baskets of wild rubber—to fill in the history that was not on display, room by room.

A sign that year promised a new museum in 2010. But when 2010 came, only a small portion of display space had changed, given over to marking the 50th anniversary of Congolese independence. The exhibit did a considerably more honest job than the one five years earlier, but it, too, was temporary, gone after a few months. Finally, in 2013, the museum announced that it was closing down for a complete revamping, and would reopen in 2017.

Behind the scenes, occasionally leaking into the press, tensions remained. That was hardly surprising, given that Europeans were spending a huge sum—the renovation bill would eventually total $83 million—to portray Africa to the world. Half a dozen scholars from Belgium’s African-diaspora community were recruited as an advisory committee, but they had to sign nondisclosure agreements, were given no authority, and came to feel that their advice was being ignored. Eventually the committee stopped meeting. One imaginative historian-anthropologist who worked at the museum for a time suggested that Africans should be invited to build a museum-within-the-museum portraying how they saw Belgium, but this idea was considered too radical. The year 2017 passed, and the museum remained closed.

Unusual as the Royal Museum for Central Africa might be, the conflict over its contents mirrors similar arguments over museums, historic sites, and monuments everywhere from Scotland to Cape Town to Charlottesville, Virginia, where a protest and counterprotest over the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee turned deadly. Elsewhere in the United States, the Museum of Man, in San Diego, recently hired a Navajo educator as its “director of decolonization” and announced that it would no longer display human remains without tribal consent. In Monticello, Virginia, Thomas Jefferson’s home now has exhibit space devoted to Sally Hemings, the enslaved mother of some of his children. When the Fraternal Order of Retired Border Patrol Officers started the National Border Patrol Museum, in El Paso, Texas, several decades ago, little did they imagine that in 2019 the museum would close for several days after protesters pasted over its exhibits with photographs of children who had died in Border Patrol custody.

Museum professionals can now turn to a sudden plethora of books, symposia, workshops, and advice blogs about “creating conversation, not controversy,” “future-proofing” a museum, and handling protesters. The main problem, of course, is that so many monuments and museums were built a century or more ago by people who took colonialism, racial hierarchy, and slavery (or at least a benign Gone With the Wind view of the American South) for granted. You “can easily rewrite a textbook,” Lonnie Bunch, the founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (and now the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution), has said, “but you can’t rewrite a museum.”

Sometimes, though, you have to try. Of course, new museums can be built from scratch, and the African American museum, which opened in 2016, is the country’s most impressive in decades. With nearly 2 million visitors a year, it is arguably more influential than any textbook. But what if your existing museum already has even more visitors, sits on hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of real estate, and owns more than 100 years’ worth of collections? Should you tear the place down? And what should you do with the stuff in it, especially when some of that stuff was booty gathered from conquered peoples at gunpoint?

More than 90 percent of sub-Saharan African items housed in museums, for example, are held outside that continent. This is the Elgin Marbles controversy writ large. Should art or cultural objects taken from somewhere else be returned to the territories they came from? Even if that makes moral sense, it doesn’t always work out. The Royal Museum for Central Africa, in fact, gave a small portion of its magnificent African art collection to a museum in the Democratic Republic of Congo some 40 years ago. But the country’s long-term dictator at that time, Mobutu Sese Seko, was famously kleptocratic, and within a few years many of those same objects began appearing for sale in Europe, some in the shops of Brussels antique dealers.

Nowhere in the United States is a museum controversy so heated as at New York City’s venerable American Museum of Natural History. Its 5 million annual visitors have included, for four years now, hundreds of demonstrators who have trooped through the museum on an Anti–Columbus Day Tour. They chant, drum, dance, and unfurl banners: rename the day. respect the ancestors. decolonize! reclaim! imagine! They deliver speeches demanding changes, a few of which the museum is slowly making.

Their prime target is the way exhibits still inherently reflect the assumptions of the museum’s 19th-century founders: that Native Americans, Africans, Eskimos, and stuffed rhinos and tigers are all, in some manner, equally exotic and museum-worthy—while that which comes from Europe or white America, being civilized rather than “natural,” does not merit being displayed. In one TV-news report, Marz Saffore, a young black woman from Decolonize This Place, the group that organizes the Columbus Day protests, stands in front of the sign for the museum’s Hall of African Peoples and points out, “There is no Hall of European Peoples. There’s no Hall of European Mammals. Because that’s called history; that’s called science.”

Why, asks a leaflet from the group, “do Indigenous, Asian, Latin American, and African cultural artifacts reside in the AMNH, while their Greek and Roman counterparts are housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art across the park?” Why are the rings on the cross section of an ancient California sequoia labeled with dates from “Eurocentric” history (Columbus “discovers” the Orinoco River, Yale is founded, Napoleon takes power) and not from the history of the peoples who lived in its shadow?

The protesters are also demanding the removal of the statue of Theodore Roosevelt on horseback (flanked by subservient African and Native American figures on foot) that stands in front of the museum. Yes, Roosevelt gave us many national parks, they say, but much of the land for those parks was cleansed of Native American inhabitants. And let’s not forget his enthusiasm for eugenics and his drumbeating for the Spanish-American and Philippine Wars and other imperial conquests. Two years ago, the base of the statue was splashed with red paint. Online, a group called the Monument Removal Brigade claimed credit: “Now the statue is bleeding. We did not make it bleed. It is bloody at its very foundation.” The museum acknowledged the protesters in July by including some of their voices in an exhibit and website called “Addressing the Statue.” But the statue still stands.

A red-paint bath has also been the fate of several of the dozen-plus statues of King Leopold II scattered across Belgium. A bust of the king was recently stolen from a Brussels park and replaced with one of Nelson Mandela. The battle over monuments, like that over museums, is global—and far from resolved.

In December 2018, more than a decade after plans for changes were first announced, the Royal Museum for Central Africa finally reopened, and a few months later I again rode the trolley to see it.

The museum now includes a new glass-and-steel building next to the original chateau, plus more space underground. One of the first things a visitor sees refers to the controversy over whether the place should have been changed at all. A well-known piece of sculpture from the old museum, Leopard Man, was acquired in 1913: a large, menacing figure of an African dressed in leopard skin, with clawlike knives in his hands, about to pounce on a sleeping victim. Now a painting by a Congolese artist, Chéri Samba, titled Reorganization, shows the statue on its pedestal, teetering on the outside steps of the museum. A group of black men and women are pulling on ropes to try to haul it away; several white people strain at another set of ropes, trying to prevent its removal. The museum director, in suit and tie, looks on impassively, arms crossed.

Many of the multilingual signs on exhibits are now apologetic. Colonialism “remains a very controversial period,” one says gingerly. “The collections of the Royal Museum for Central Africa have been composed by Europeans; it remains a challenge, therefore, to tell the colonial history from an African perspective.” Another points out, “Collections often say more about who has collected them than about the society in which the objects were made and used. From the outset, Africans opposed colonization in different ways, but this is hardly apparent from the collections of this museum.”

Such apologies are just the sort of thing that enrage the “old colonial” lobby. A former official of a group of colonial-era veterans has denounced the museum for featuring “the worst slanders.” An open letter from another critic accused the director of being “politiquement correct.” An online screed condemned him for “Belgium bashing.”

The apologies, however, continue throughout the building. Some of them are vague and bland (their wording no doubt the outcome of testy arguments and compromises), but at their best they implicitly acknowledge that almost anything on public exhibit anywhere is a political statement—something few museums do. For example, the institution has a huge collection of photographs, but signs now explain: “They were almost exclusively made by white people and mainly show their perspective.” “They were carefully staged.” “Political leaders and dignitaries from rural areas were presented as ‘noble savages,’ while laughing city dwellers conveyed the image of a model colony.”

This is followed up with a remarkable early photo showing just such a portrait of a “noble savage” being staged. Two sun-helmeted Belgians are preparing to photograph an unsmiling, half-naked Congolese man in profile. One of the white men has his head under a black cloth behind an ancient tripod-mounted camera; the other has his hands sternly on his hips, a few feet away from the black man, as if he has just ordered him into position. It is hard to imagine a more vivid portrayal of the colonial view of Africa, captured in the making.

A notorious part of the old museum was its giant rotunda, filled with huge statues of such figures as The Worker (a black man with loincloth and shovel), The Warrior (a black man with spear), Justice (a gilded, robed white woman, scales in one hand, sword in the other), and Belgium Brings Well-Being to the Congo (a gilded, robed, saintly white woman comforting two black children). Now a sign describes the “colonial vision” behind the statues: “Belgians are presented as benefactors and civilizers, as if they had committed no atrocities in the Congo, and as if there had been no civilization there beforehand.”

The sign goes on to explain that the statues have landmark status and cannot be removed. So the museum invited a Congolese artist, Aimé Mpane, to create a work as “an explicit response.” This is an enormous chiseled-wood representation of an African man’s head, sitting on a base the shape of Africa. As a piece of art, it did not move me, but I liked the idea of one sculpture as an answer to another. It reminded me of a recent article in The Chronicle of Higher Education, in which the sociologist Troy Duster, a grandson of the anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells, suggested something similar for the United States: Why not leave Robert E. Lee in place, but put up a statue of William Lloyd Garrison or Frederick Douglass next to him?

Although the museum’s “Colonial History and Independence” gallery takes up a disappointingly small portion of the building’s total space, it does not stint on displaying colonialism’s dark side. Video monitors show historians—almost all of them Congolese—talking about the vast death toll of the slave-labor system, and about Belgian complicity in the 1961 assassination of the independent Congo’s first democratically chosen prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, who gets a corner of the room all to himself. Several of the atrocity photographs that helped rouse world outrage about the slave-labor system are on display. So are examples of the ubiquitous chicotte, a whip made of twisted sun-dried hippopotamus hide with sharp edges, used to beat enslaved laborers, sometimes to death. A photograph and a painting show it in use. Also on exhibit are some of the pamphlets and books written to expose the system, both by Belgians and by foreigners. Visitors can see cartoons mocking Leopold, and transcripts of statements made by black witnesses before a 1904–05 investigative commission—testimony suppressed for more than half a century, first by Leopold and then by the Belgian government.

Though this exhibit has drawn the most ire from the “old colonial” lobby, it also clearly reflects some unresolved differences among the museum staff. Whoever chose the chicottes and other objects on display had a far different sense of history than whoever compiled the interactive historical timeline on computers in this gallery and several others. It omits several major anti-colonial rebellions and never mentions the large mutinies among black conscripts in King Leopold’s private army. Slave labor gets mentioned only in passing, and the scale of the international protest movement is barely hinted at. The timeline notes, however, the appointments of various governors-general and ministers of colonies, and the creation of the Congo’s first Boy Scout troop.

A greater shortcoming is that nothing here really links the exploitation of the Congo’s riches—ivory and rubber in the early days; copper, diamonds, uranium, and much more later on—with Belgium’s own prosperity. Congolese profits helped fund, for instance, the giant archway of the Arcades du Cinquantenaire, a Brussels landmark. And how many of the mansions that visitors pass on their trolley ride to the museum were built with such wealth? A 2007 survey showed that the fortunes of nine of the 23 richest families in Belgium had roots in the colonial Congo. A good museum should make you start looking at the world beyond its walls with new eyes.

But few museums do so. Where in the United States can you find a first-rate exhibit showing the connections between American corporate profits and our long string of military interventions in the Caribbean and Central America? You can now see slave quarters at restored southern plantations, but only recently, for example, have Providence and Boston announced plans to create museums linking their city’s prosperity to the slave trade. New York’s enormously wealthy Brown family (of Brown Brothers Harriman) even owned southern slave plantations outright—and, incidentally, were early patrons of the American Museum of Natural History.

A major problem that museum suffers from is echoed at the Royal Museum in Belgium. Exhibits about the lives and history and art of African peoples continue to share a building with stuffed animals—an elephant, a giraffe, multiple crocodiles, snakes, butterflies, insects—and rocks. The same space remains a container for everything African, whether human, animal, or mineral. One of the African-diaspora scholars consulted by the Royal Museum urged that at least the animals be given to Belgium’s large Museum of Natural Sciences, but her advice was not taken. As an astute critic put it in the Belgian magazine Ensemble, the institution remains un musée des Autres, a museum of Others.

Despite the limitations of the revamped Royal Museum, it now has one feature that is quietly stunning. One wall has long held an immense marble panel on which are written the names of 1,508 Belgians who died in the earliest years of colonization, before Leopold’s personal rule over the Congo ended in 1908. The panel also bears a quotation from the king’s successor, his nephew, Albert I: “Death reaped mercilessly among the ranks of the first pioneers. We can never pay sufficient homage to their memory.”

To any African, this is outrageous. Most of these “first pioneers” were anything but heroes. They were ambitious young adventurers, hoping to get rich quick on rubber and ivory; Joseph Conrad portrayed them excoriatingly in Heart of Darkness. They died, for the most part, from diseases like malaria, sleeping sickness, and dysentery, for which there was as yet no cure; their ends were sometimes hastened by drink. A startlingly high number, estimated at nearly one in 200, committed suicide. And the crafty Leopold (who never set foot in his prized colony himself) kept secret the fact that roughly one in three Europeans who went there during the first decade of his rule perished; that statistic would have discouraged others from going.

But the greatest injustice of all is that during the Leopold years and their immediate aftermath, at least several million Congolese died—worked to death gathering rubber; shot down in rebellions; starved in the rain forest, where they fled to escape the slave-labor system; or felled by the famines that took place when men were turned into slave laborers and their wives and daughters into hostages. The names of nearly all of these victims are unknown.

But we do know the names of a handful of Congolese who died in Europe during Leopold’s reign. A few were children, sent as an experiment to a church school in Belgium; others were among those exhibited at world’s fairs like the one on the very site of the museum in 1897. The Congolese who died at the 1897 fair were refused tombs in the consecrated part of the nearby parish cemetery, and were buried instead in a common grave in the ground reserved for suicides, paupers, prostitutes, and adulterers. In tribute to seven of these Africans whose lives ended so far from home, a Congolese artist, Freddy Tsimba, has engraved their names, and the dates and places of their deaths, high on a row of floor-to-ceiling windows that face the marble panel. When the afternoon sun comes through the windows, these names are projected in large letters of shadow on top of the Belgian names on the panel. It is a haunting, ghostly overlay that reminds you of just how many ignored and forgotten lives throng unseen behind the history we are accustomed to celebrating.

This article appears in the January/February 2020 print edition with the headline “When Museums Have Ugly Pasts.”