It was in May 2008 that Jonathan Zittrain first sounded the warning. While the argument was raging, as it is now, about censorship of the internet by governments seeking to control what their populations read – in countries such as China, India and Pakistan – the professor of cyberlaw at Oxford and Harvard universities had another concern: what if it were actually the gadgets we used that were in effect censoring the world that we could connect to, and the things we could do?

Zittrain fretted that smartphones, which were just beginning to take off, might actually limit what users could do online compared with devices such as personal computers. Besides the obvious difference – a smartphone is light and can be slotted in a pocket; a personal computer is power-hungry and bulky – there's another subtle but essential difference. Personal computers are "generative": they can be programmed to do more than they were set up to. Smartphones, on the other hand, generally can't be programmed directly by the user. For the most part, they're appliances, as limited in what they can do as a coffee maker.

In his book, The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It, Zittrain noted: "We care little about the devices we're using to access the net … we don't think of that as significant to its future the way we think of [direct censorship]."

But does the rise of appliance-like smartphones – and more generally of "walled gardens" such as Facebook, Myspace and Google+ – presage an age where we simply cut ourselves off from uncomfortable truths online because our devices, or the sites we use, won't show them to us, like a North Korean radio made so it cannot be tuned to unauthorised sources?

The question is urgent. Facebook has passed 845 million users, and smartphones are outselling PCs so quickly that in 2010 the research company Gartner forecast that as soon as next year mobile phones will overtake PCs as the most common way to access the web, used by 1.82 billion people, compared with 1.78bn net-connected PCs.

But answering it is complicated, says Dr Richard Clayton of Cambridge University's computer laboratory, who has extensively researched the censorship and oversight systems used by many countries and companies, including the UK and British Telecom's "CleanFeed" system, used to filter child pornography.

"Facebook can cause people to disappear from history, vaporising their pages and everything they wrote on your wall, as if they were never there," he points out. For Facebook, everything – every user, every wall entry, every photo – is just an entry in a giant database, which can be removed at any time by someone with access to that database. (It could be you, or an administrator.) The complication comes in trying to suggest that doing that or not doing that is "wrong".

"Everybody applauds the idea that there shouldn't be an open space where paedophiles swap material," says Clayton. "Or where al-Qaida can swap material and recruit. And then it gets harder – you have Facebook groups where you have Muslims who want to march through Luton to protest about our activities in central Asia. Facebook has a rather fun arrangement so that they can set up groups like that, but they aren't visible in the UK [where they would count as hate speech]."

So Facebook roots out what it considers against good taste, which (as Clayton points out) generally means content that would not be allowed under the US first amendment, since it is an American company. A guidebook for its moderation staff recently became public, revealing that images of breastfeeding would be banned if nipples were exposed, but deep flesh wounds and crushed heads would be OK.

While such rules seem peculiar in Europe, almost to the extent of being the reverse of what is expected, Google+ has also demonstrated the same American prudishness on its Google+ social network, which insists on people using their real names.

As San Francisco-based journalist-turned-venture capitalist MG Siegler discovered, the site banned him from using a photo with a rude gesture – an extended middle finger – for his profile; when Siegler reposted it, Google removed it again. The key to the problem: Google wanted to show Google+ profile pictures in search results, and if those included pictures that some might find offensive, Google could lose business.

Censorship? Heavy-handed US-biased restriction? Or reasonable move to keep the web clean? Tom Anderson, the co-founder of Myspace, who was automatically everyone's friend when they first joined, wrote an open letter (on Google+) to Siegler, in which he said: "Every social network has the policy you're decrying, and why shouldn't they? It's a public sphere." He compared it to wearing a racist T-shirt in a shopping mall: "Security would probably ask you to leave." He added that it had been very difficult at Myspace to keep up with "offensive" photos; without that control, a social network "turns into a cesspool that no one wants to visit … sorta like Myspace was".

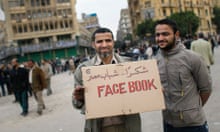

But social networks played a big role in the Arab spring of 2011, with Facebook and Twitter both cited as key to getting the message out from oppressed groups. More recently, Syria has become the source of many important videos showing the suffering of citizens attacked by their own government. Those can be seen on YouTube – though not, of course, by citizens within Syria itself.

The fears about "walled gardens" sometimes reflect concerns that are as much about business models as principles.

Facebook does not let Google or any other site index the vast majority of its content; a tiny file called robots.txt on its homepage stops search engines from grabbing details of photos, feeds or other data. Only the most limited information can cross that wall – and that worries Google, which relies on being able to index everything (don't forget its mission statement: "organise the world's information and make it universally available") and then to sell adverts against it.

John Battelle, who runs online advertising network Federated Media, says Facebook poses an existential threat to Google. "The old internet is shrinking and being replaced by walled gardens over which Google's crawlers can't climb," he noted earlier this year, as Facebook prepared its flotation. "Sure, Google can crawl Facebook's 'public pages', but those represent a tiny fraction of the pages on Facebook, and are not informed by the crucial signals of identity and relationship which give those pages meaning."

In the same way, Apple's iTunes store is available on the web, and Google can index it, "but all the value creation in the mobile iPhone and iPad app world is behind the walls of Fortress Apple. Google can't see that information, can't crawl it, and can't make it universally available."

In that sense, as Facebook gets bigger, and sells advertising to its users, it poses an increasing threat to Google – because to many, the space outside Facebook will look more and more like an untamed space where scams, malware and piracy thrive. "Google's business model depends on the web remaining open, and … that model is imperilled," Battelle adds. "The open web is full of spam, shady operators and blatant falsehoods. Outside of a relatively small percentage of high-quality sites, most of the web is chock full of pop-up ads and other interruptive come-ons.

"It's nearly impossible to find a signal in that noise, and the web is in danger of being overrun by all that crap. In the curated gardens of places like Apple and Facebook, the weeds are kept to a minimum, and the user experience is just … better."

Even video sites such as YouTube and Vimeo can be thought of as a form of walled garden: videos are removed at the request of copyright owners and law enforcement. Often, they're dismissed as just being repositories for "cute cats" videos (with user-generated films such as "Charlie bit my finger" still near the top of the all-time list). But as Ethan Zuckerman, director of MIT's Centre for Civic Media, pointed out in a Vancouver Human Rights lecture, Cute Cats and the Arab Spring, sites such as YouTube, Facebook, or Twitter are the best place for dissidents to post grievances and findings.

Those sites don't offer the best protection for dissidents, Zuckerman argues – for people can often be identified through their posting or web identity – but their power is that governments, even repressive ones, block them at their peril. If YouTube suddenly becomes invisible, people begin to wonder why and begin to ask questions – which in time, given the connectedness of our modern civilisation, will mean that they find out.

An earlier version, from 2008, pointed to how the overhead views of Google Maps had shown precisely who owned property in Bahrain – which often turned out to be the royal family. But what about the mechanisms that are increasingly being used to foment or report revolution – the smartphones with internet connectivity, or the computers being used to upload photos or video taken with cameraphones?

Zittrain has expressed fears about how the devices we use to connect to the net have moved away from being fully capable personal computers – where in theory you can write programs that can use any capability of the computer – towards appliances such as the iPad or iPhone, with tightly limited functionality and access to the underlying operating system software, where only "allowed" programs can be installed from a vendor-maintained store. He calls such a process "tethering".

"From the start my worries about appliances permanently tethered to their makers have been that the tethering won't be limited to smartphones," Zittrain sayss. "Rather, the closed smartphone architecture is the canary in the coalmine for all of consumer computing. That's why I've said the PC is dead, even as the PC's form factor may remain. In the past year we've seen the introduction of the App Store on the Mac PC – not just iPhone and iPad."

Even Microsoft, which ushered in the era of the personal computer running software that in theory could be used to write any program, is heading in the same direction. Versions of Windows 8, to be released in the autumn, will also use Metro Store for apps, which Microsoft will control.

Adding new programs will be hard; in effect, websites will become the new programs. Zittrain notes that although you can still side-load software – that is, transfer it from another source, such as the internet or a memory stick connected to the machine, that is a reversal from the paradigm that ruled for years.

"What a transformation: the principal way of acquiring software for the past 30 years is now through a side door rather than a front one," he says. "I'm both awed and worried about what's happened since 2008."

Zittrain concedes that people like convenience and security – and they're entitled to. But he says there's a qualitative difference between now and then. "No one tried to get Bill Gates to alter Windows so that undesirable apps and associated content – undesirable to someone other than the user – couldn't be accessed. Today is different: if Facebook or Apple allow objectionable apps on their platforms, or Google in the Android Marketplace, or Microsoft in the Metro Store, regulators can say: take it down."

That's a subtle shift, but important. Media commentator Jeff Jarvis says Apple's iPad is "sweet and pretty but shallow and vapid ... I see danger in moving from the web to apps," he said. "The iPad is retrograde. It tries to turn us back into an audience again."

The same broad criticism is applied to smartphones, where not just Apple's product, but almost all platforms prevent any sort of easy access to the underlying code; there's no "command line interface" for a smartphone, no black screen and blinking cursor as you can find on a Windows or Apple computer, if you look hard enough.

Part of that is for the protection of the wider telephone network, says Clayton. "Because phones are talking to the wider telecommunications system, which isn't secure, the wireless side of phones tends to be locked down very tight."

But on the app side, the extent of user lockdown varies between platforms. Apple's iPhone is tightly controlled: you can't distribute an app on to iPhones except by putting it through Apple's App Store – and the company has previously removed apps in China at the government's behest, such as in 2009, when apps about the Dalai Lama were removed.

In that, Apple was like Google, which at the time maintained an operation inside China, and self-censored its content, offering a link to Chinese searchers to explain why the content was censored – but not to ways to find the results they wanted. Apple offered no such indication that the store was censored.

With smartphones now outselling PCs every quarter, and China forecast to become the world's largest smartphone market this year, ahead of the US, the question of whether smartphones are a "reductive", limited platform, or "generative" like a PC looks like an increasingly important one.

Battelle says the shift to mobile is unstoppable. "The PC-based HTML web is hopelessly behind mobile in any number of ways," he wrote on his blog. "It has no eyes (camera), no ears (audio input), no sense of place (GPS/location data). Why would anyone want to invest in a web that's deaf, dumb, blind, and stuck in one place?"

Yet that wealth of data on mobiles isn't necessarily leading to a more web-like experience. Clayton says that "we are seeing more locked-down platforms than before" on smartphones – pointing particularly to Apple, but not excepting others.

The biggest, and best-selling, exception is Android, the smartphone software that Google offers free to handset makers. "With Android, there's a wider choice of where to download apps from" – many companies, including Amazon, offer their own Android "app stores" – "and Google doesn't hold your hand as much." The search giant can still "kill" apps if it judges them to be malware.

So far, there do not seem to have been any occasions when the Chinese government has demanded that an Android app is wiped from phones – though its Great Firewall can prevent people inside China accessing the official Android Market from which apps can be downloaded, rendering the problem moot. Indeed, Android Market has been blocked a number of times inside China, and many users there prefer the unofficial ones that have sprung up; though those, of course, will come under the eye of the government.

In total, Android is outselling all other smartphone platforms – though probably not because eager would-be programmers and tinkerers are taking it up, but because carriers can offer them cheaply. "[Apple's iPhone and iPad software] iOS and [Google's] Android now represent fascinating hybrids," says Zittrain. "Third parties can write apps – and how they do! – but the manufacturer, to varying degrees, can control whether those apps can reach their audiences."

Even so, there's no easy answer. For example, the success of Research In Motion's BlackBerry phones in many Middle Eastern countries has come about because they allow teenagers to communicate directly with the opposite sex, without having to meet face-to-face – because that could fall foul of strict religious laws. Similarly, Facebook offers a way for teenagers to "speak" in ways that might be banned in the physical world. To some teenagers – and activists – the fact that the BlackBerry's PIN-based Messenger system can't be tied to a phone, yet lets people stay in touch, is the perfect reason for using the platform. Though it can be decrypted – if the government goes to great lengths – in general it will be private, which suits its younger users perfectly.

Zittrain's real worry is that "the personal computer is dead".

His conclusion is a call to arms: "We need some angry nerds" – people capable of breaking out of the walled gardens.

Indeed, the US government has found some: it has backed projects such as "the internet in a suitcase", which could set up a telecommunications network inside a country separate from the existing infrastructure.

Zittrain acknowledges such projects, but for the wider world, he says, "convenience is great. I wouldn't call for a return to the green blinking cursor of [Microsoft's pre-Windows] MS-DOS or the [text-based] Apple II. But we should build architectures that permit innovation and experimentation if consumers wish to go 'off-roading'."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion