In the United States, two out of every three searches go through Google, which serves up a total of three billion search queries per day. "Googling" has become so ubiquitous that the company has become a verb in English (and in other languages, too).

Given that most of us use Google several times a day and may also use it to send e-mail, to plan our calendar, and to make phone calls, questions commonly arise about how all of that data is used. Google has said that it needs access to such large amounts of data as a way to “make it useful” and to sell personalized ads against it—and to profit substantially in the process.

However, a March 2012 study from the Pew Internet and American Life Project found that two-thirds of Americans view a personalized search as a “bad thing,” with 73 percent of those surveyed saying that they were “not OK” with personalized searches on privacy grounds. Another recent poll of California voters recently reached similar results, as “78 percent of voters—including 71 percent of voters age 18-29—said the collection of personal information online is an invasion of privacy.”

Short of masking your online trail with a VPN or going through Tor all the time, it’s hard to avoid the watchful eye of Sergey and Larry. What's a privacy-conscious Web searcher to do? For those who worry about such issues, privacy-minded search alternatives in various stages of development do exist—even if they're only taking the tiniest bite out of Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo’s search engine market share.

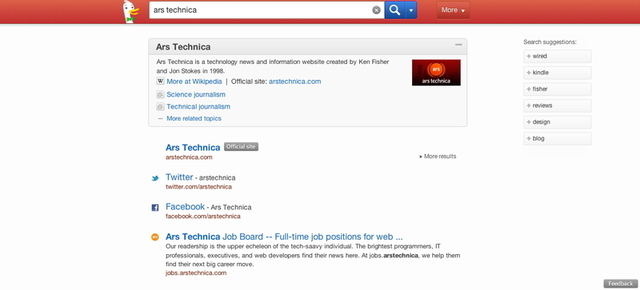

DuckDuckGo

One of the top privacy search engines has a name reminiscent of a children’s game: DuckDuckGo. The site was founded two years ago but has recently taken off; just last month, it hit an all-time record of 1.5 million searches per day and its daily search traffic has grown by 227 percent in three months.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...