In 1983, advertising pioneer David Ogilvy summarized his mission as follows: "I do not regard advertising as entertainment or an art form, but as a medium of information. When I write an advertisement, I don't want you to tell me that you find it 'creative.' I want you to find it so interesting that you buy the product. When Aeschines spoke, they said, 'How well he speaks.' But when Demosthenes spoke, they said, 'Let us march against Philip'."

This Hellenic manifesto certainly gets to the point. Unfortunately, Ogilvy's battle cry offers little guidance for helping us view advertising spots from a half century ago—the kind that fans of the AMC series Mad Men see being worked out alongside the personal lives of Don Draper, Peggy Olson, and Pete Campbell. The dictum offers even less aid for considering ads that hawk items so outmoded that even Ogilvy's skills could not inspire us to march on our local electronics store.

Take, for example, sales literature for mainframe computers made and marketed in the 1950s and 1960s. Even after reading a classy three color foldout for a room filling UNIVAC or PDP-5, would you buy one today? No way unless you are a dedicated collector. But now, thanks to the Computer History Museum's wonderful exhibit titled Selling the Computer Revolution, we can appreciate the considerable creative effort that went into making these machines attractive to business owners and consumers.

The public framing of computers shifted from the 1950s through the 1970s, the exhibit notes. In that first decade, advertisement and brochure makers focused their attention on engineers.

"Speed, efficiency, economy, and reliability," were the standard buzzwords. But as computers got smaller, cheaper, and more powerful, ads encouraged consumers to see them as more than just calculating machines. Pamphlets foregrounded the growing female labor force that ran them first as key punch operators and programmer assistants, then as programmers and computer buyers themselves. These advertisements also took on an increasingly futuristic and almost utopian edge.

"It was to have been the Nuclear Age," declared one 1976 ad for IBM. "It became the Computer Age."

Let's follow the computer marketing trail, and watch how the message evolved.

Well endowed

Mainframe computers in the 1950s like J. Presper Eckert's UNIVAC were big and expensive. They required entire rooms and in some instances building floors for their proper maintenance. And so computer literature emphasized maximum processing bang for the corporate buck. The RCA 501, for example, "has been endowed with the work habits that result in low work unit cost-speed, economy of motion, accuracy," the machine's 1958 sales brochure explained, "and with the capability of applying these efficient work methods to the full scope of business routines."

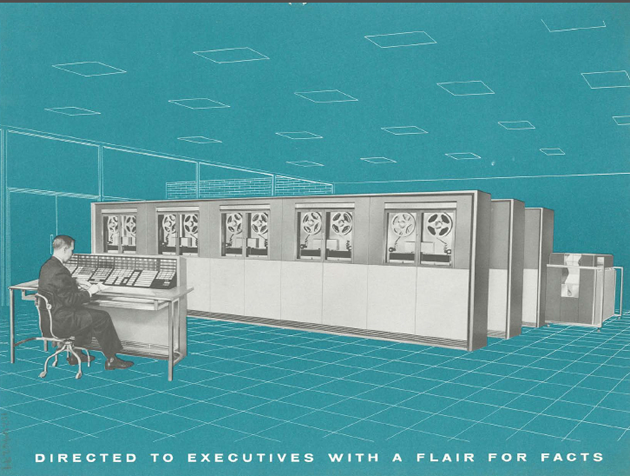

Brochure pictures of the mainframe turned the unwieldiness of the system to its advantage. "Directed to executives with a flair for facts," boasted an image caption, which depicted a suited man easily running the whole fifteen panel RCA 501 shebang from a single console.

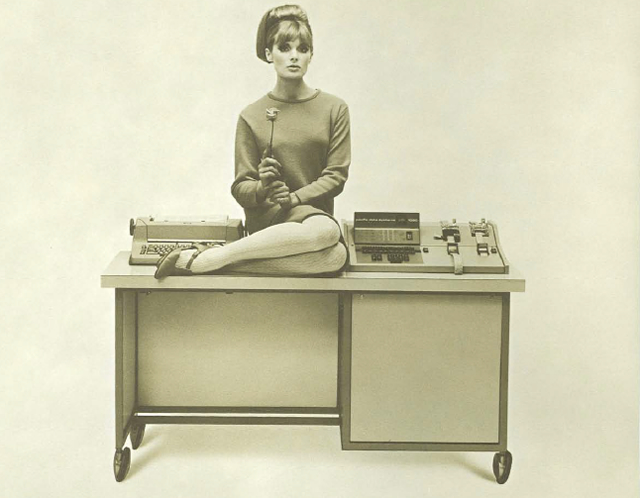

Similar images billboarded literature explaining the UNIVAC file system and its general operation. Or they showed women employees skillfully running the show.

"WHAT'S YOUR PROBLEM?" asked the UNIVAC brochure. "Is it the tedious record-keeping and the arduous figure-work of commerce and industry? Or is it the intricate mathematics of science? Perhaps your problem is now considered impossible because of prohibitive costs associated with conventional methods of solution."

No worries, advertisers assured readers. They tackled anxiety about programming costs by summarizing prospective budgets in concise, easy to remember figures. "How much computer can you buy for less than $1000/MONTH?" asked the opening page of a 1955 brochure for the Bendix G-15 computing system. The large type answer was "PLENTY," followed by a photo of a crew assembling the operation in somebody's office.

Of course, as the buyer read on, he or she discovered a few extra details about the Bendix. It cost about $1,030 a month to lease an alphanumeric system. The sales price went "as low as $14,900." But to give the reader an idea of how concerned clients were about computing power, consider the details this brochure offered about processing times.

BENDIX G-15 SPECIFICATIONS

Execution Times

Add and subtract:

Single precision—0.27 msec.

Double Precision—0.54 msec.Multiply and divide:

Single precision—2.16 to 16.4 msec.

Double precision—2.16 to 32.8 msec.

Given the costs of computing in the 1950s, no advertiser could omit a careful accounting of processor specifications and speeds. That attention to detail would taper down a bit in next decade.

reader comments

50