This question is a cliché, still, it bears repeating: What is the opposite of losing? I come back to this question each time I feel the aching, gnawing, debilitating, infuriating, paralyzing, outer-body experience of grief.

When someone is suddenly gone and you remain, it is like you are living on a different planet but of course, you are not. You are earthbound; you field advertisements in your inbox for half-off sales at the Gap: you want to laugh at the universe. What else can I lose? Half off; are you kidding me? The Gap, really, could the universe be more of a cliché? I'm empty; damn you. What does the Gap have to say about half-off of empty? As Joan Didion writes in The Year of Magical Thinking, "Life changes in the instant. The ordinary instant." It's exactly the odd juxtaposition of the prosaic and life-altering that people in grief must navigate. How they do this is a topic we need to address, as grief is often mistaken for depression, anger, even madness. But grief is its own monster that for too long has been living in the shadows of silence and shame.

There really isn't much public space for mourners. Grief makes people uncomfortable. Perhaps that is because we are embedded in a culture of winning (is that the opposite of losing?) Add to that the fact that we are consumed with the notion of finding (certainly that must be the opposite of losing, right?) So where do mourners go with their grief? The River Styx has lost its relevance; today, mourners are turning to social media. What that says about our culture, I'm not sure, but I think it's worth examining.

Leeat Granek, a health psychologist who studies grief, points out that the inclination to express feelings of loss is nothing new, and though the expression of grief on social media might seem unsettling perhaps because social media has a reputation for being a trivial, reductive and curated expression of our lives or for being linked to feelings of depression and inadequacy by comparing our lives to the lives of others, there is much to learn about the nuances of exchanges in social media and what they say about human connectivity. "Supporting people in grief means being with them in their pain and sorrow and taking our cues from them and what they need. It's not helpful, logical or useful to pass judgment, and in fact, I think it's precisely that judgment that often causes grievers the most pain."

What follows is an account of several people who have announced their grief in Facebook statuses. When I came across their posts in my feed, I honestly didn't know how I felt about this act of public sharing, sandwiched between pictures of someone's lunch or selfies, and this is coming from a woman who writes openly about intimate and sexual experiences. My disquietude did not sit well with me, so I knew I had to mine it. Let me clarify, I did not consciously have a feeling about the appropriateness of these posts; in fact, in some cases, they rattled me so hard I wanted to recoil from the world of social media. But I also had a feeling that my reaction to others' grief and public sharing of it was part of a larger phenomenon that speaks to how our culture internalizes loss. Here's what Leeat Granek, PhD told me:

It's important to point out that it's not in anyone's service to judge what is right or wrong, dignified or not on Facebook or elsewhere. I think the need to pass this judgment says more about our own discomfort with grief and the end of life than it does about whether someone is mourning 'appropriately'.

I couldn't agree more. The impulse to pathologize how mourners grieve is a recently new phenomenon due in part to the increasing role social media plays in our day-to-day existence. But, as Granek points out, the pathologization of grief is not serving mourners well, nor is it doing much for the rest of us who are trying to go about the "ordinary instants" of our lives. Something we might not want to acknowledge is that death is one of those ordinary instants because it happens to us all. Yet, we haven't quite figured out how to react to mourners, especially people who mourn in a public space like Facebook. I'm hoping that by reading the stories below of people who shared their loss in status updates and by digging into their impulse to share, we can open up a new public space for grief that is devoid of shame and judgment.

Wendy Chin-Tanner is a founding editor of Kin Poetry Journal, the poetry editor at The Nervous Breakdown, the author of Turn, a collection of poetry and co-author of the graphic novel, American Terrorist. Last year, she suffered her second miscarriage in a row, and as she puts it, "Suddenly no longer pregnant at 7.5 weeks, I was flooded by a tidal wave of rage." She continues:

I was angry because I had told so many people about this pregnancy and I was ashamed to have somehow 'lost' it. I was angry at the very fact that I was feeling this shame. And angry that there was an expectation that I should have waited until it was a 'sure thing' before announcing it, as if there could ever be a 'sure thing' in this world anyway. I was angry because I am expected to carry a triple burden: the burden of fertility; the burden of pregnancy itself; and perhaps most of all, the burden of silence if a pregnancy is lost.

Her anger -- not only as a symptom of her grief -- was also a reaction to the lack of information about prenatal healthcare and birthing choices; that there was no real public forum for women and their families to discuss openly the more unpleasant aspects of pregnancy, childbirth and miscarriage. The silence she felt compounded her loss and fueled her anger. And so, she took to Facebook and posted the following status update:

Miscarriages suck, and one of the worst things about them is the silence that surrounds them. As a culture, we are socialized to not talk about them publicly or worse, pretend they never happened. Well, f--k that. Right now, I am going through my second miscarriage in a row: first one at 5.5 weeks; this one at 7.5 weeks. So, friends, please share your experiences. I'd love to hear your thoughts.

Wendy explains a main impulse behind her post was that she saw it as a way out of silence, isolation and shame -- all feelings associated with grief. "I posted this not because I wanted pity or sympathy," she says. "I did it because I thought it might make me feel better to speak publicly about what I was going through in the hope that other people would share their experiences, too, and that by sharing, we might all feel a bit better in the realization that we aren't alone."

The responses she received from her post helped her reposition her loss. She came to understand miscarriage as not only a woman's experience, but as "a universal experience, and silencing it is harmful to all of us." Perhaps most profoundly, she realized, "We can change things simply by speaking out."

Although Wendy's loss is very specific, in a more holistic sense, the feelings around her loss speak to the way people treat those in mourning. "The standard responses," she explains, whether in the form of platitudes or denial, are not only inadequate, but can even exacerbate feelings of shame, isolation, and anger." Certainly, we fall back on clichés when we are at a loss ourselves on how to categorize experiences. Learning how to comfort -- or at the very least be with -- people in mourning requires us to be authentic with ourselves and sit with feelings and sensations that make us not only uncomfortable, but that we spend much of our daily lives trying to ignore. No one wants to confront the inevitable harrowing experience of death and loss. We live in a culture that tells us if we examine pain, we are dwelling in a negative space. I have to wonder if this notion is serving us well. The truth can be messy, but so is the experience of being human, and as Wendy puts it, "When people speak the truth to one another, all sorts of amazing things happen."

Porochista Khakpour is a novelist and essayist, author of Sons and Other Flammable Objects and The Last Illusion. She describes herself as an "internet community early adopter." She frequented AOL chat rooms in mid-'90s, where she found "lifesaving Internet friends." Since then, she has always been grateful for online spheres like Facebook as a place to find community with people who are not necessarily "IRL friends," but friends nonetheless. In February, mourning the loss of writer and performer Maggie Estep, who Porochista describes as a "dear friend" and with whom she "instantly clicked," the novelist took to Facebook to write a series of long posts about her friend's passing. "Posting to Facebook helped me work through my own feelings about it," she explains. "Some places had contacted me to write something for pay and I just couldn't take money for it. I felt the best place was public posts on Facebook. I didn't want any attention really. I just wanted my dear amazing friend back."

Some readers might feel that the death of a friend, no matter how close, is incomparable to, say, the loss of a family member. Even within family members, our culture looks to create some kind of hierarchy for loss. Besides the fact that for many of us, friends become family, this notion of a hierarchy for grief seems anathema to understanding the complexity of mourning and how we as a culture can fully internalize loss and sorrow, which we must in order to heal. A hierarchy for grief reminds me of a time when, enmeshed in a dysfunctional relationship, unfulfilled by my work and plagued by insecurities, I was mired in a period of unshakable depression. I remember sitting on my shrink's couch saying, "I'm a semi-affluent woman living a life of privilege. What about the women in Chad who are really suffering?" The thing is pain, like any other emotion, is relative. While perspective is important, as is the inclination to look outside yourself, outlining a hierarchy for grief doesn't seem to mitigate the anguish of others.

Porochista continues, "I don't have a new family and I'm not that close to my old family so friends are all I have. When Maggie died, I immediately turned to Facebook. First of all, she loved being online and was very active on all social media. I wanted to look for traces of her final day or two, to desperately make sense of what happened I guess."

Facebook can be seen as a digital scrapbook, a journal, a way to collect memories in an interactive way, and therefore, it is a modern-day narrative, a timeline to "make sense of what happened." Narrative has a long history of shifting as technology for recording and observing stories evolves. Porochista elaborates:

I like what we used to call 'over sharing' now just sounds outdated and absurdly scold-y. Posting makes the world a less lonely place. I've committed myself -- and I've announced this -- that I will post the bad with the good. Many times someone I didn't know described a personal battle or victory and it really resonated with me and altered my day in a way real life interaction did not. I don't feel that's a problem; I just feel this is our reality and I will make the best of it.

Victoria Barrett is a writer, editor and publisher of Engine Books. In the 14th week of her pregnancy, she learned that the baby she was carrying had trisomy 13, a chromosomal anomaly that causes severe defects that most fetuses cannot survive. She explains, "An ultrasound revealed severe developmental damage to every system of her body, confirming that she was among those who would die during gestation. Though most trisomy 13 babies don't survive even that long, ours did. For my own safety, to end the baby's suffering, and because the doctors all gave her no chance of survival, we had to terminate the pregnancy." As a writer and publisher, Victoria uses Facebook to connect with writers and, in turn, writers use Facebook to support her press. She says, "My use of Facebook tends to reveal the world as I see it, but through a critical lens. I'm a deeply political person, and I post a lot of political material, particularly advocating for women. Outside of political stuff, I only post material I think my Facebook friends will find funny or interesting, and lots of stuff about literature. I don't self-reveal purely for the sake of doing so."

So, when most of us were updating our pages with "year-end posts" as 2013 came to a close, Victoria was grieving the loss of the daughter that had been living inside of her for 14 weeks. Her status update disclosing this news read:

If you've been wondering what my annoyingly cryptic status updates were about, here's the situation: Last summer Andrew and I decided to have a baby. We got pregnant in September. But the baby had a chromosomal condition, trisomy 13, that the doctors all considered 'incompatible with life'; at 14 weeks, she had severe deformities to every part of her body. We had to terminate. We've spent the last three weeks dealing with the news and the loss. It's hard to talk about, but we're going to be okay.

Like many people, Victoria uses Facebook to communicate with friends and acquaintances who are either "far-flung geographically," or with whom she isn't terribly close. She felt her fatigue and devastation after her loss was becoming evident in her online persona. But what was she hoping to gain by announcing her grief on Facebook? "I don't know -- this is a good question," she says. "I didn't know if anyone would comment or want to discuss it -- it's so personal and painful. I often feel at a literal loss for words in the face of others' pain and grief, so I didn't know whether others would feel the same. But the post generated something like 90 comments, and I've gotten at least 15 emails, as well, sharing condolences."

She also explains, "This thing that happened to me is an indelible part of who I am, already, so I wanted to be candid about that. I carried a baby. I planned a life as a mother, and my husband planned a life as a father. Those lives didn't come to pass. That's not going to change or end." Boiled down to simplest terms, Victoria's impulse to grieve publicly speaks to the human need to be seen, heard, and understood by others, especially because grief can be isolating. "Social media gives us a different kind of opportunity to reach out than previous eras offered. When you grieve in public, or express your grief in the presence of others, you're making a translation from your language--the language of loss--to theirs."

Aaron Johnson, a DJ and producer, was part of the band Hypernova which brought the Iranian post-punk/dance rockers and political refugees, The Yellow Dogs, to America. "We toured with them for a year. All of us were a crew; we were a family. They were a piece of me." Mid-November of last year, three members of the Yellow Dogs, Ali Eskandarian, Arash Farazmand and Soroush Farazmand, were shot to death in their home in Brooklyn. The story became national news, which added an additional layer to Aaron's grief over the violent murders of his friends. "It was crazy hearing the details of their murders on the news that morning. I couldn't get a hold of anyone and as hard it was to hear the actual version, it was better than having my imagination run wild," he says.

Within moments of seeing the news story, Aaron, who relies on Facebook to promote his music and appearances, but also admits is on it "more than I should be," took to his keyboard to ask for "lots and lots of e-hugs."

He delves into why it is people might feel shame or embarrassment around grief. Perhaps because he's a musician or just a sensitive guy, his response as the only male represented in this story is pretty gender-neutral. "People are scared to be seen as wounded. Even though we're only talking about an emotional wound, I think we still have a survivalist mentality that weakness makes us vulnerable, which in turn makes us easy prey. With social networks, we are able to broadcast emotion as information and not be physically seen on our knees with grief. In private, I was on the f---ing ground though."

Two concerns popular in the lexicon of grief include what to say -- or not to say -- to offer condolences, and is there any way to achieve closure from this type of loss? So what do people want to hear when in mourning? Further, is it possible to say something meaningful over social media? Aaron explains,

I never want to hear the word 'sorry,' which has become the go-to condolence word. I get it; I understand that people say it because they are here for me and care about me. But I think it can have a better impact to reach out to someone and offer whatever you can do to help comfort them; lend an ear; buy a drink; offer them space. I never want to hear the word sorry from someone who never did anything wrong to me again.

I think what Aaron is trying to say, is that sometimes we grieve just to have someone listen.

"In terms of feeling closure," he says, "I wish I had more of it. While it's true that the term 'closure' doesn't close anything at all, I think what it's come to mean is 'the ways we try to move on,' which is a very important thing to try to do. I think people end their own lives far too often this way: not remembering that the oceans flowed long before their existence and will continue to flow long after." In this way, we are reminded to think outside ourselves, whether grieving or consoling, and whatever can get us out of the traps of isolation is a good thing.

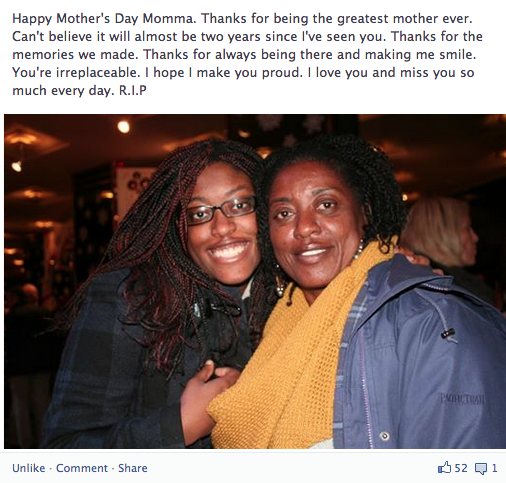

Kimberley Lionel is a college student studying writing, psychology and language. I've known her since she was in seventh grade, when came to me for help with her writing. As she puts it, "Writing is an escape from reality. Reality sucks. I would rather live in my imagination." Over the years, she's been just as much a mentor to me as I've been to her. When she was 17, her mother was brutally murdered in a case where police have yet to apprehend a suspect. Kimberley was not in the house at the time of the murder, but when she did return, her home had become transformed into a crime scene. "Reporters outside were asking me inane questions like, 'Was she a good mother?' The only thing I said to the press was that she was the best mother in the world."

As the youngest of the people I interviewed, Kimberley grew up with Facebook, and it plays an integral role in her adolescent social life, both back in high school and now at college. "I wouldn't say I'm addicted, but I check it constantly," she says. In the days following her mother's death, Kimberley used Facebook to private message her friends about her mother's murder, however she waited six months before posting about her grief. "The first time I posted about my mother's death was on her birthday. I addressed a post to her, telling her things I wanted her to know. But I put it out there because I wanted people to hear me. I wanted other people to know. I post to her/about her because I want compassion and support and to voice myself to the world."

Kimberley's resilience, her ability to hold onto herself by bravely declaring, "You can never get over it; it just gets better," reminds me of a James Baldwin quote that I come back to when I experience moments of loss that feel intolerable. "For, while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new, it always must be heard. There isn't any other tale to tell, it's the only light we've got in all this darkness."

You'll notice that all of the people whose stories I've shared are artists in one-way or another. Those of us on social media are storytellers too. We tell our stories because we must -- and there are myriad reasons that compel that impulse. Confronting grief, whether our own or the grief of others is part of the human storyline. Doing so in a public way can only open up new spaces for us to exist in times of darkness and in times of light, as well as in the murky twilight of ordinary instants.