The October 26 retail release of Windows 8 heralds a new era for the world’s most widely used operating system, in which both tablets and traditional desktops are (theoretically) given equal consideration.

Overhauling Windows to make it usable with both fingers and mouse-and-keyboard is very much a response to Apple’s success with the iPad and iOS. But Microsoft is imitating Apple in one very bad way, by limiting the distribution of Metro applications to a Microsoft-controlled app store.

The introduction of Apple's iOS App Store in July 2008 had a huge impact on the way software is distributed to mobile devices. It has been replicated on every major mobile platform, the Mac desktop, and now Windows. The iOS App Store represents the extreme end in the open vs. closed dichotomy we're going to look at in this article—on iPhones and iPads, nothing can be installed unless it comes from the App Store, and Apple has final say over what goes in the store. But iOS isn't the only model, and it's not the model Microsoft should follow in Windows 8 and Windows RT.

Windows has been successful for decades in large part because of its openness, allowing developers to distribute software to users however they'd like. By bringing Windows to tablets, Microsoft could strike a blow for openness in a market dominated by a closed system. Instead, Microsoft is bringing the same restrictions found on iPads to both Windows tablets and PCs.

There are security benefits to a closed app store model, particularly for less tech-savvy users who may not understand all the dangers on the Web. There are also, arguably, convenience benefits; end-users can be reasonably confident that the apps they download will work correctly and be at least marginally useful. So it's not unreasonable for Microsoft to make Windows' default behavior as restrictive as the iPad's, which is what Microsoft is doing with Windows RT and the Metro portion of Windows 8.

But while these security and convenience benefits might be enough to justify the existence of a curated app store, they don't justify the decision to make that store the only option for all users. Informed users should be allowed to install applications from wherever they want.

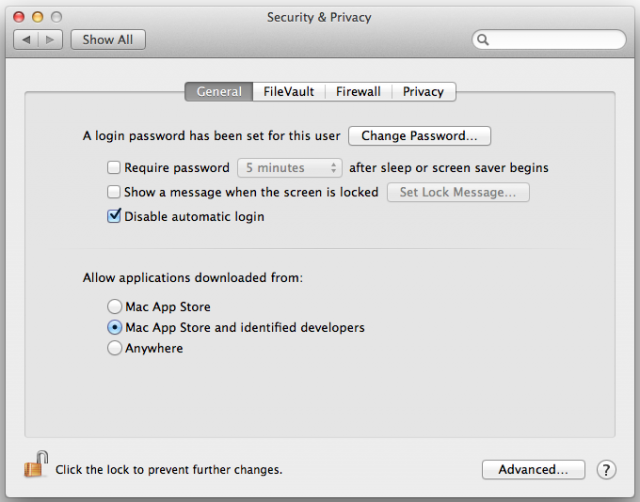

Microsoft is intent on making the Windows Store the primary avenue to get Metro apps. While we think the iPad approach is the wrong one, a good model for Microsoft to follow comes from one of Cupertino's other products—OS X. Android also offers a more open approach, but we feel the one that's right for Windows 8 is something like the Mac's Gatekeeper, a combination of a restrictive app store and an escape hatch that lets people go around it.

The new rules

"Open" is an overloaded term. We're advocating a more open Windows 8, but by using the word "open," we're not referring to open source. In the context of this article, we define an open platform as one that provides documentation to developers for free, has no restriction on who may develop applications, and no restriction on what types of applications can be developed. Free access to developers would be nice, but it's not really a dealbreaker.

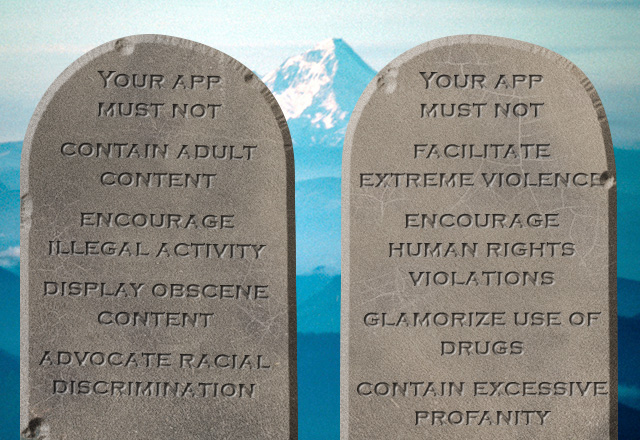

The Windows Store for Windows 8 and Windows RT does offer free documentation to developers. There are restrictions on who may develop applications, but they mostly come down to location and money. As long as you live in one of the 120 or so approved countries and pony up $49 per year for individuals or $99 per year for corporations, you're in (although Microsoft reserves the right to revoke a developer's account). Just as Apple does on iOS, Microsoft takes a 30 percent cut on app sales.

The most troubling area in which the Windows Store falls short of openness is the restrictions on what types of apps can be developed and distributed. In the Store, Microsoft exercises control over both the editorial content of applications and their functionality.

Microsoft is introducing two new operating systems: Windows RT for ARM-based touchscreen devices, and Windows 8 for x86 computers. Each is split into two user interfaces, the traditional desktop everyone is familiar with and the Metro (or Modern UI) tile-based interface that replaces the Start menu and emphasizes tablet-y apps.

Windows RT is as locked down as an iPad. There is no option to install traditional desktop applications. Only the ones pre-loaded by Microsoft, specifically the built-in applets that come with Windows, and Office Home & Student 2013, are available. Developers can distribute Metro apps to Windows RT, but only through the Windows Store—which can only include apps that don't fall afoul of Microsoft's restrictions on content and behavior.

Windows 8 is more open—but still troubling. Developers are allowed to write applications to the desktop and distribute them however they'd like, just as on Windows 7. But the same Windows Store restrictions for Metro apps found in Windows RT are present in Windows 8.

"We're going to ensure that the Windows 8 Store is the only place that Metro style apps can be distributed," Microsoft's Ted Dworkin said a year ago when introducing the store. Microsoft's public statements on the matter have not changed since. There are exceptions for developers to sideload apps for testing, and for businesses to distribute custom apps for employees (just as on the iPad), but developers can't distribute Metro apps to a general audience without going through the Windows Store.

So what, you say? The “desktop” portion of Windows is still there. Just as they could with Windows 7, Vista, XP, and previous versions, developers can build any Windows app they want and let users download it from anywhere. Windows, at least the part users are familiar with, is still just as open as it always was. Metro, or whatever it’s called, is just extra functionality in addition to the desktop. As such, defenders of the restrictions argue that users therefore haven't lost anything.

They're correct—and will continue to be correct, for a while. With only a few thousand applications in the Windows Store at this date, Metro won’t take over the traditional desktop anytime soon. But in the long run, Microsoft’s emphasis on Metro points to a future in which Metro is the primary user interface for Windows desktops and tablets, for mouse-and-keyboard users and touchscreen users alike. And, unless Microsoft changes course, it will be locked down in ways the traditional Windows desktop never was.

Chipping away at user freedom, one device at a time

Richard Stallman's dream of giving users the freedom to modify every aspect of every piece of software they use, even if you believe in it, has no realistic chance of coming true this decade—or century, perhaps. We certainly have some open source software floating around the Ars Orbiting HQ, but our definition of user freedom is more forgiving. As long as the Microsofts and Apples of the world don't restrict development of third-party applications, and let users install software from any source, we're happy to call the Windows and Mac operating systems "open platforms."

Windows and Mac have long been open in this respect, but Apple's decision to lock down the iPhone and iPad (and the success of those devices) has initiated, or at least accelerated, a trend toward OS lockdown. The iPhone and iPad, if they're not jailbroken, allow installation of apps from just one source—Apple's App Store.

Let us be clear—we dislike Apple's decision to prevent users from installing any application they want. It's why we prefer iPads when they're jailbroken. When the iOS App Store debuted in 2008, the true impact of the restrictions was unclear, and not necessarily troubling. The store provided convenience of a kind we'd never really seen before, and HTML5 was there to provide any functionality that couldn't be had through the store. At the same time, we'd seen other smartphone platforms without the kinds of restrictions that Apple imposed, and they were a user-hostile mess. Back in 2008, we could have believed that the lock-down was essential to make the smartphone a mass-market success.

But times have changed. We've learned a lot about just how important apps are, and that HTML5 is presently a poor alternative to real apps; the HTML5 end-run around the store restrictions isn't enough. With Android, we've seen a successful mass-market smartphone platform without the same tight content restrictions. Finally, the increasing use of the iPad for functions traditionally associated with desktops has meant that the restrictions are encroaching on more traditional computing devices. Together, these things make Apple's closed model less forgivable.

Add to that the knowledge that Apple uses its position as curator to make some very questionable decisions—actions such as a (temporary) ban on a satirical application created by a Pulitzer Prize winner are maddening—and the wholly closed model makes us even more unhappy. We wonder what else we're missing out on.

There are also signs that Apple's iOS rules are slowly creeping into the desktop. The latest versions of OS X use "Gatekeeper," a set of restrictions in OS X that by default prevent installation of applications from outside the App Store or from unrecognized developers.

But getting around Gatekeeper is easy—Apple provides an officially supported escape hatch. No typing in the terminal is required, you just flip a switch in a settings menu, and apps can be installed from anywhere. Still, the out-of-the-box behavior of OS X partially mimics the restrictions in iOS:

The standard justification for these restrictions is generally "security." If users can install software not explicitly rubber-stamped by Apple, they're more at risk. That may be true up to a point, but it's hard to imagine this strategy scaling very well. Apple has access to all the source code for Mac OS X and its own software. It developed much of the code itself, and knows it intimately. Yet OS X, Safari, iTunes, and Apple's other software periodically contains critical security flaws.

For applications submitted to the store, Apple does not even receive source code. Is it really credible to believe that Apple has performed a thorough analysis of these 700,000 apps to ensure that they don't have security flaws that can harm users? Of course not. In fact, we know it has not: security researcher Charlie Miller proved that by tricking Apple into publishing a proof-of-concept app that exposed iOS security flaws. Apple's verification processes may manage to keep the worst of the worst away from users, but this falls a long way short of providing a cast iron safety guarantee.

On the other hand, we know that Apple has rejected applications that are harmless, solely because they offend the company's sensibilities. In one recent case, Apple refused to publish an application that tells users when American drones have killed "enemies" of the state.

Another argument put forward is that the lockdown is in some sense a response to consumer demand. As popular as Apple's handheld products are, we could argue that consumers are voting with their wallets in choosing a mobile operating system that allows app installation from anywhere and has multiple app stores. Android has surged past the iPhone in total smartphone market share, and is gaining in the tablet market with the success of the Nexus 7 and Kindle Fire. Android has had its security problems, to be sure, but they're not enough to drive consumers away. Android is getting more systematically secure, too; Miller says the latest version of Android has been hardened and will be difficult to exploit.

Android takes an approach that's similar to the Mac's Gatekeeper. By default, apps can only be downloaded from the Google Play store, but users are allowed to change a setting allowing installation of apps from "unknown sources." Like the Mac, this offers a "safe-by-default" approach without completely shutting users out from unofficial app distribution channels.

We've seen that security can dramatically improve with strong under-the-hood protections that prevent silent installation of malicious applications, while still giving the user the right to choose what may be installed on their system. Microsoft provides perhaps the best example of this, with its User Account Control technology in Windows Vista and Windows 7. So why can't Microsoft secure Metro without locking out non-Store applications?

Android's app store is very open, with developers being able to publish applications after only an automated review to weed out malware. Microsoft's app store model is a lot more like the one Apple uses than Google's, and that's fine. But Microsoft needs to couple that with a concession to developers and users who don't want to be restricted to just the Windows Store.

reader comments

182