Apple's traditional desktop computing business has suffered many indignities over the past decade. Once Apple's flagship product line, the Mac first found itself playing second fiddle to the iPod—a mere music player—in the early 2000s. Today, matters are worse; on a graph of Apple's revenues, the Mac now appears as a thin strip of earth while iOS devices are the mountain that sits upon it.

Apple presented last year's release of OS X 10.7 Lion as part of a turn "back to the Mac." Ostensibly, the tagline was Apple's promise to bring innovations from its mobile operating system back to Mac OS X. But more broadly, it also meant that the Mac would receive more of Apple's attention.

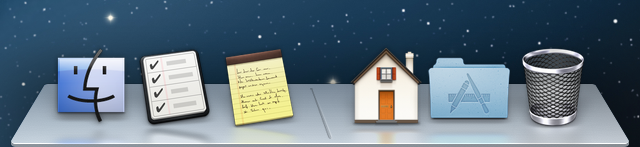

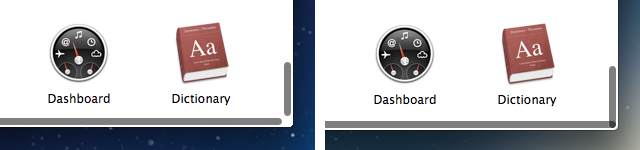

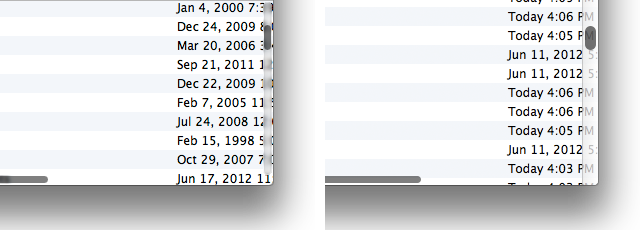

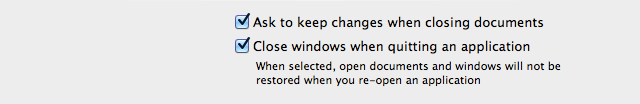

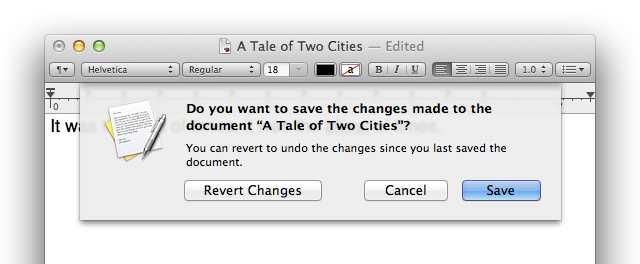

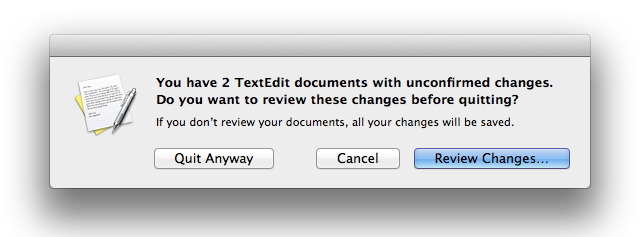

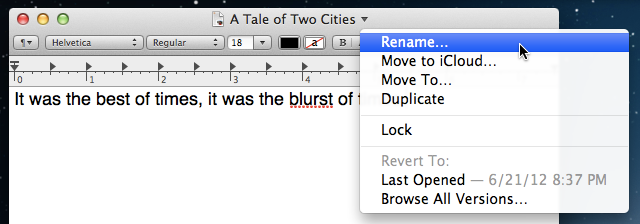

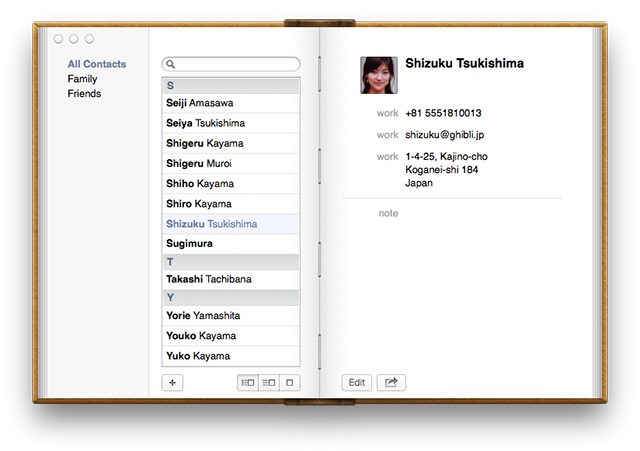

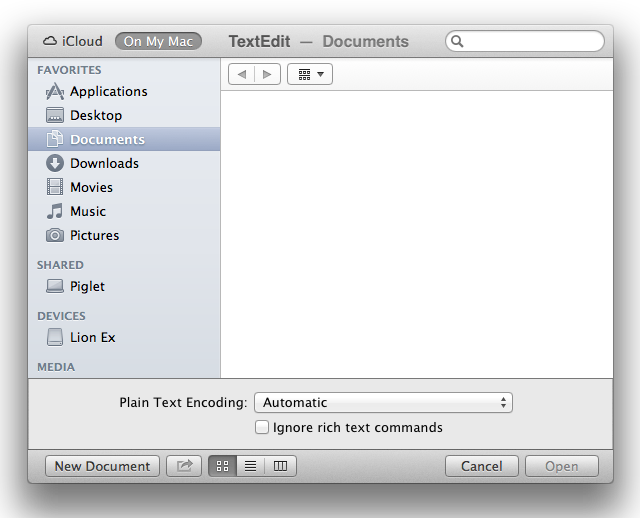

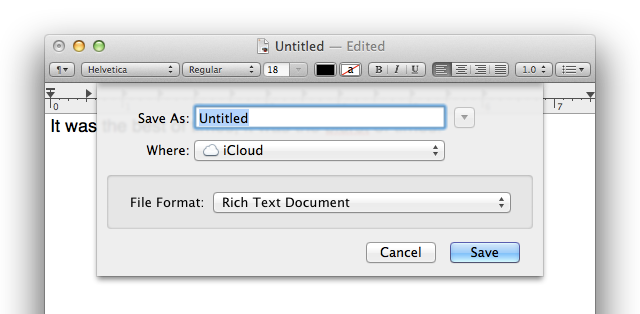

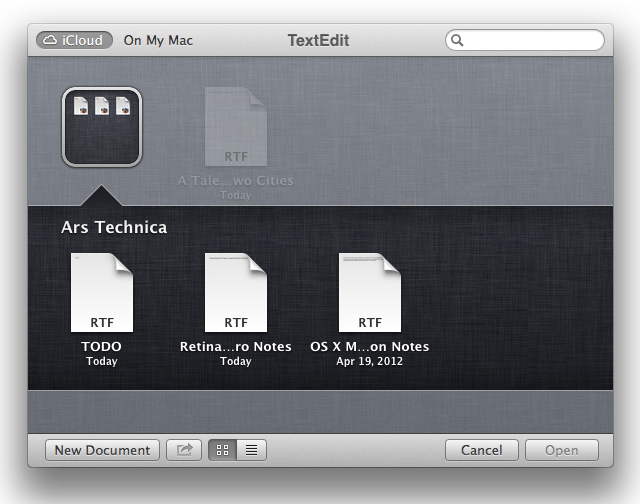

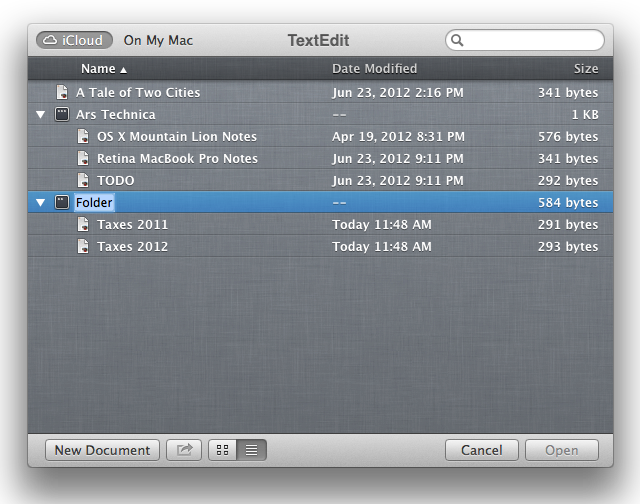

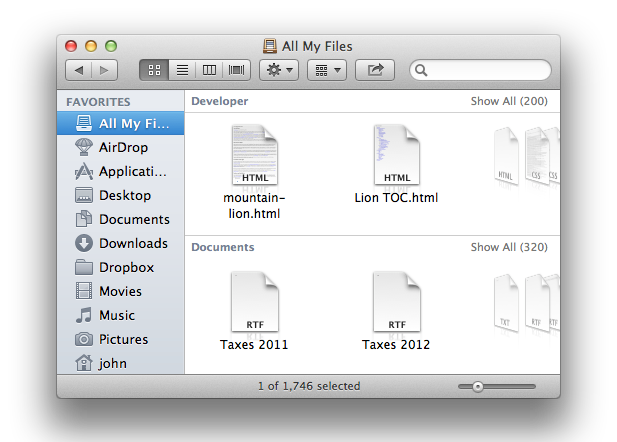

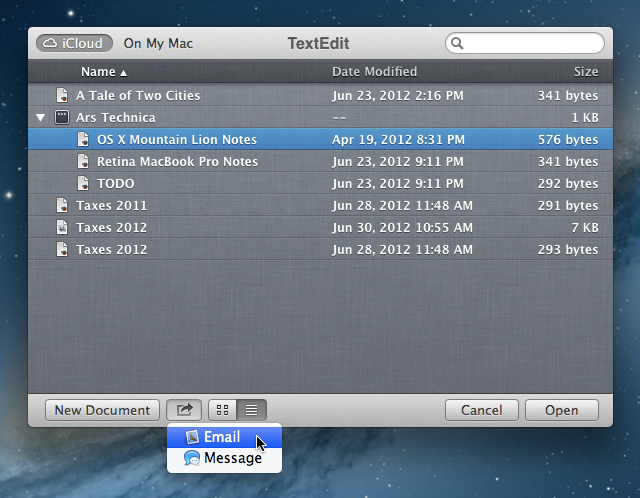

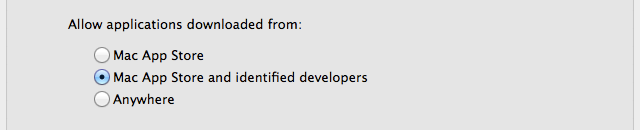

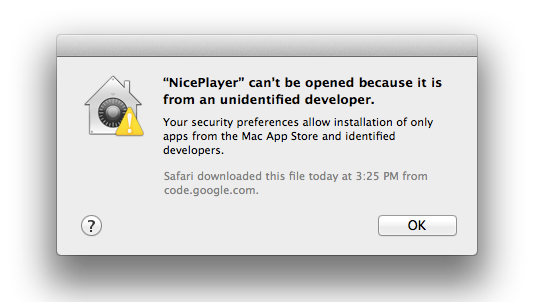

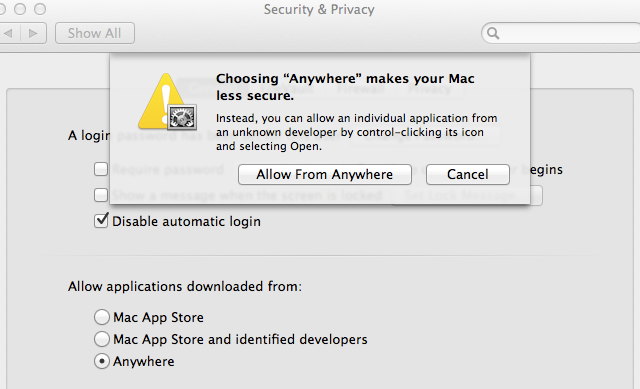

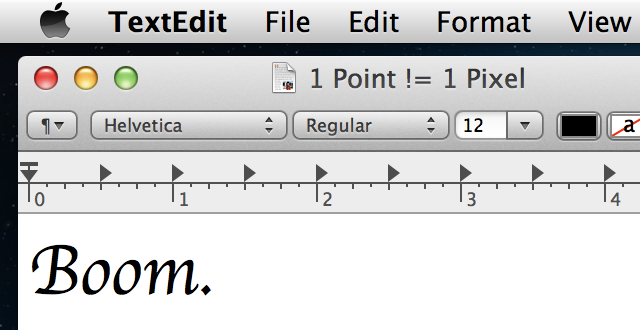

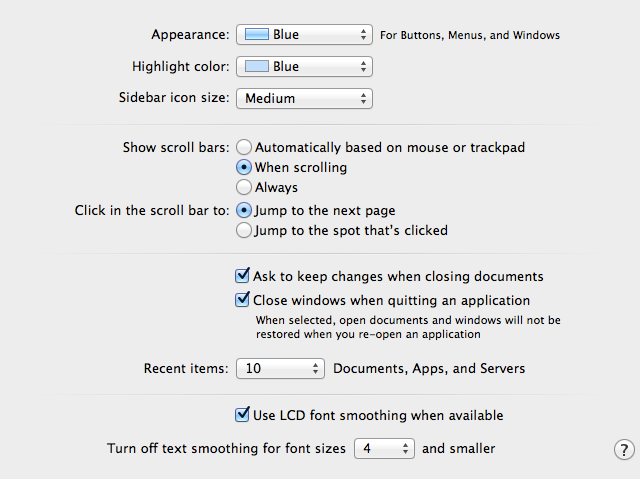

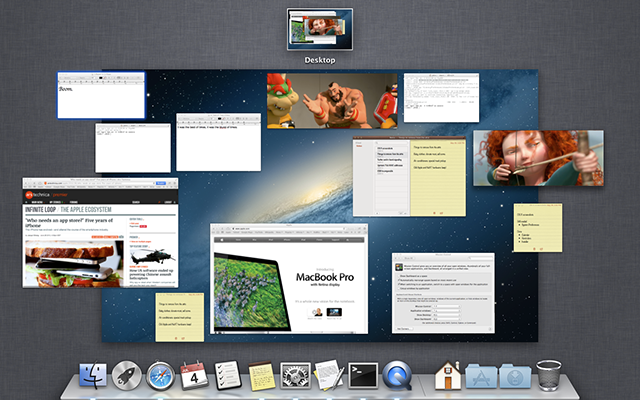

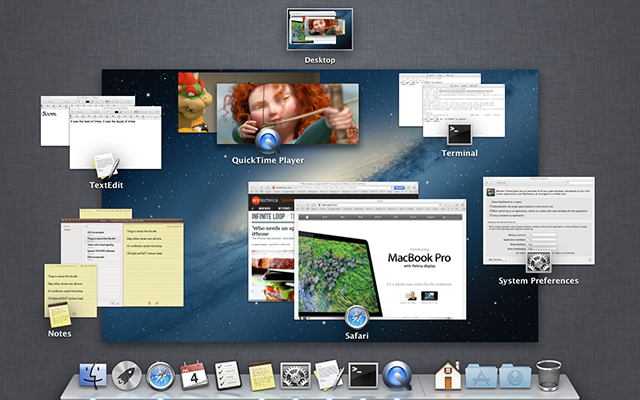

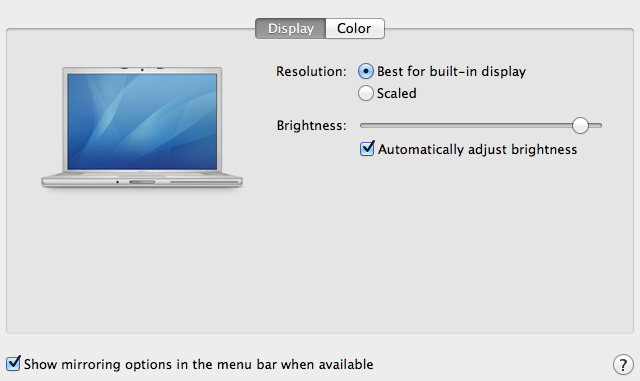

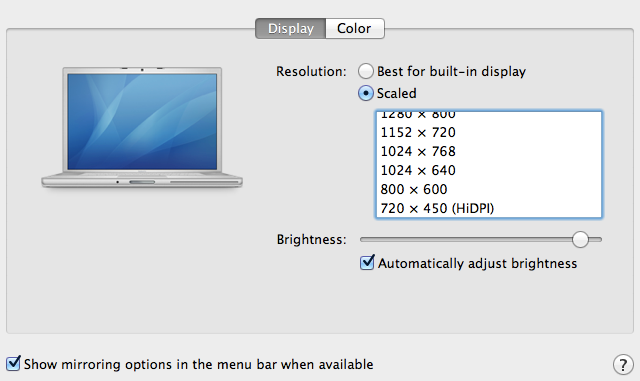

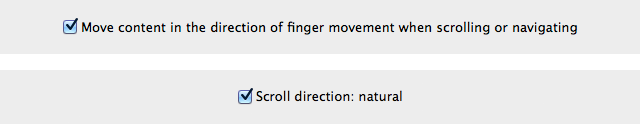

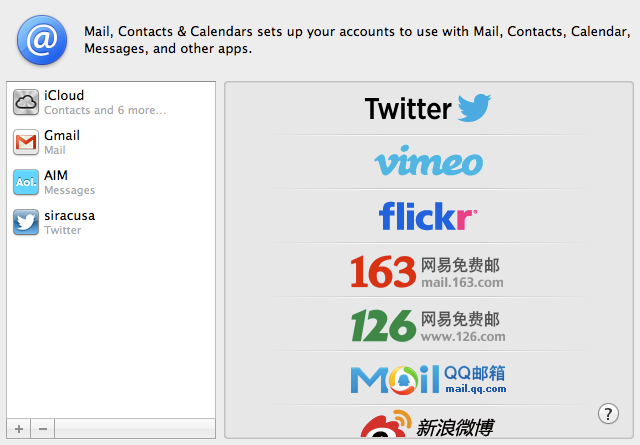

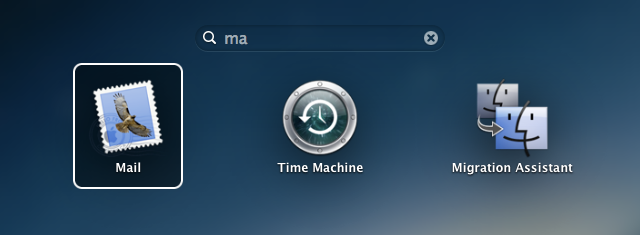

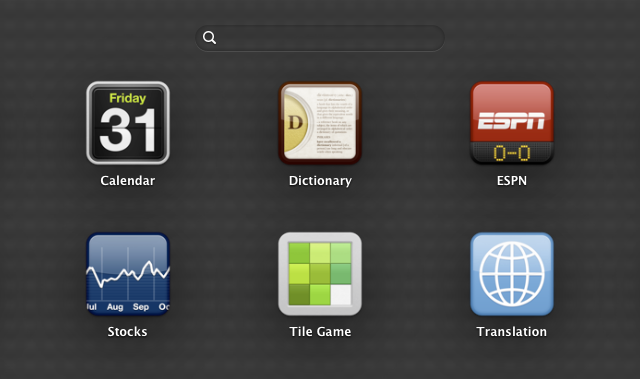

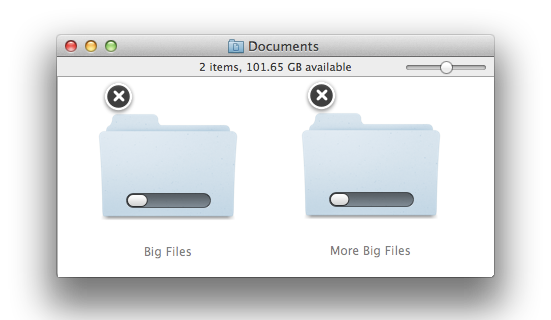

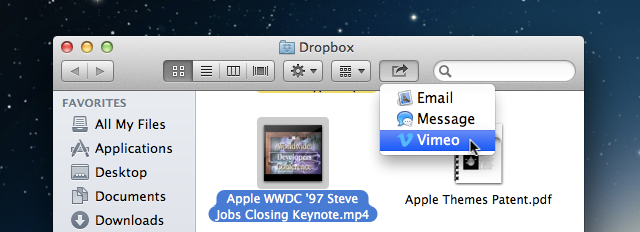

That attention resulted in some dramatic changes to aspects of the operating system that had not been reconsidered in decades: application launching, the document model, process management—even basics like window resizing and scrolling. As Apple's newly refocused gaze fell upon its desktop operating system, many parts of it were deemed archaic and unworthy of continued existence.

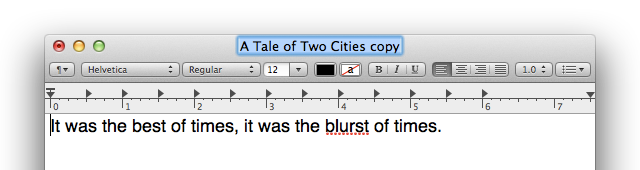

At the end of last year's Lion review, I concluded: "[Lion] marks the point where Mac OS X releases stop being defined by what's been added. From now on, Mac OS X should be judged by what's been removed." Unfortunately, the surgery was not a complete success. There were… complications.

Sins of the father

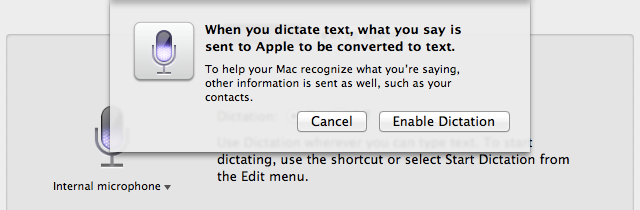

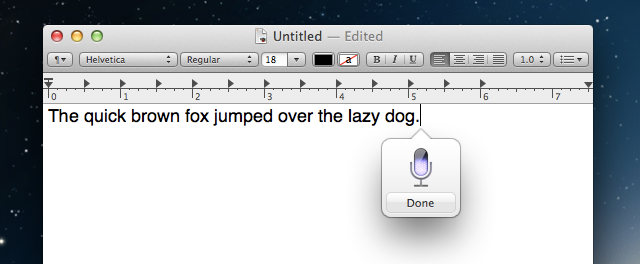

Apple's intentions were noble. Lion's new features said all the right things: "Stop worrying about saving your documents; Lion's got you covered. You don't need to keep track of how many applications are running; let the OS handle those details for you. Don't bother mucking around in the Finder, your applications are only a few clicks away. And scroll bars? Getting them out of your face is like a breath of fresh air. Trust me, this is going to be awesome."

Loading comments...

Loading comments...