You've probably seen an article trying to pinpoint the portion of the electorate that will make the difference in the 2012 election. Whether it be soccer moms, Latinos, Africa -Americans, Jewish Americans, college-educated voters, workin- class whites, Asians, most of this analysis is interesting, if a little overboard.

Yet, there is one group of Americans who loom large in number and receive little attention in presidential elections: felons. In all states but Maine and Vermont, currently incarcerated felons are not allowed to vote. In an additional 13 states, plus the District of Columbia, felons who have completed their term of imprisonment can vote. Another five states allow voting after parole has been completed, and another 18 allow voting to resume after both parole and probation have been carried out. Ex-felons (that is, former offenders who are out of prison and who have served parole and probation) in 12 states lose the right to vote permanently despite paying their "debt to society".

A 2002 study estimated that about 4.7 million American felons in total were disenfranchised for the 2000 election, while a 2004 estimate pegged the number at about 5.3 million American felons for the 2004 election. These numbers are merely estimates from past years, but they give us an idea that about 2-3% of US citizens are barred from voting because they are (or have been) felons.

The restriction on felon franchisment is not too unusual in comparison to the rest of the world. While many countries such as Canada, Denmark, and Israel allow almost all convicted offenders to vote, others such as Brazil, India, and the United Kingdom completely bar prisoners from voting.

What is different about the US bans is that, from state to state, they may continue to be in effect after a person leaves prison. Only six countries, including Chile, Finland and Germany, in a 45-country study belong to this group. In the cases of Finland and Germany, voting rights are usually restored quickly or a ban imposed only for a period of time.

Because of America's unique rules, some 3.5-4 million citizens as of 2000 and 2004 respectively are out of prison, but not allowed to vote. A smaller, but still significant, 1.7-2.1 million US citizens who could be officially deemed "ex-felons" were legally denied the right to vote in 2000 and 2004 respectively.

These voting laws overwhelmingly disenfranchise African Americans, who make up 40% of the disenfranchised felon/ex-felon population. (Blacks make up only about 13% of the general population.)

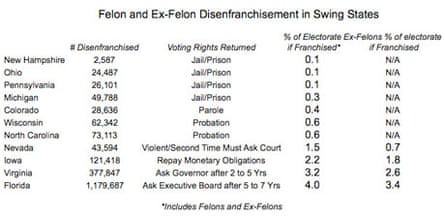

Presidential elections, however, are not determined nationally, but on a state-by-state basis. I've pulled the felon voting laws from the 11 states that I believe will determine the outcome of the election. I've assigned each felon a 30% chance of voting – if given the opportunity per Jeff Manza and Christopher Uggen's 2004 study. Using this data and the overall turnout in each state from 2004, I determined what percentage of felons would have made up of the electorate had they been allowed to vote.

Not surprisingly, states such as Colorado, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania with the loosest regulation of felon or ex-felon voting rights are the states where felons would have the weakest potential impact on the voting pool. Disenfranchised felons, however, would make up a significant percentage of the electorate, from 1.5% to 4%, in Florida, Iowa, Nevada, and Virginia – if given the right to vote (in all these states, even ex-felons have obligations to fulfill before being allowed to vote).

Concentrating solely on disenfranchised ex-felons, we see that they would have comprised 2.6% in Virginia and 3.4% in Florida (of the respective voting electorates).

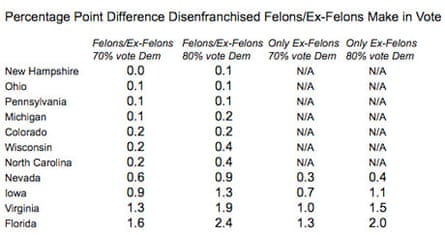

How would these felons change the election outcome? Partly because about 40% of disenfranchised felons are African-American, we can extrapolate that a fairly steady 70-80% of felon voters would have cast their ballots for the Democratic presidential candidate between 1972 and 2000. I estimate that Al Gore would have increased his margin over George W Bush by at least 500,000 votes in the 2000 election. That may not seem like a lot, but he only won the popular vote by 500,000 – so this would have doubled his margin.

Yet, it's in the swing states where felon voting would likely have made the biggest difference. Let's assume nationally that 70-80% of the vote would go to the Democratic candidate. If ex-felons and felons were allowed to vote in Iowa, Virginia, or Florida, they would probably have changed the margin by at least a percentage point in each state and potentially upward of 2.4 percentage points in Florida.

Even if we hone it down to "ex-felons" only, they would have been numerous enough to change the margin by up to a percentage point in Iowa, 1.5 points in Virginia, and 2 points in the crucial swing state of Florida.

These are huge changes in a close election: 2 percentage points distributed to the correct swing state would have reversed the presidential result in the 1960, 1976, 2000, and perhaps the 2004 election. These changes are certainly much larger than the expected Democratic gain, for instance, if Latinos were actually to vote in proportion to their overall percentage of the eligible population.

Of course, whether or not felons should be allowed to vote is another question – and one that even divides members of the same party. My guess is that if you are a Democrat, your answer would almost certainly be yes. If you're a Republican, then the numbers might make you more inclined to answer in the negative.