Libraries across America are facing swingeing budget cuts and uncertain futures. But here in New York, home to the second-largest library in the country, the future is now.

The hottest cultural controversy of this already hot summer concerns the New York Public Library (NYPL), and a plan to disembowel its main building – a plan that will slice open the stacks and "replace books with people", in the words of the NYPL system's CEO, Tony Marx. It's enraged writers and professors, demoralized a staff already coping with layoffs, and called the entire purpose of the system into question.

And the debate is getting bitter. Hundreds of writers, from Peter Carey to Mario Vargas Llosa, have gone on record against the plan. An exhaustive exposé in the literary magazine n+1 raised the temperature, and the current issue of the New York Review of Books contains page after page of tetchy point v counterpoint. Whatever the fate of our library, a lot of people are going to be very angry when this is all over.

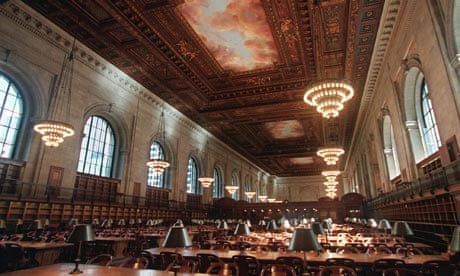

The New York Public Library comprises 87 branches in three of the city's five boroughs, but the prize is the big beaux-arts central facility on Fifth Avenue, 101 years old, with its pair of marble lions guarding the entrance. Even those who have never been to the city know the place – it's the setting of the first scene of Ghostbusters. As is the way in Bloomberg's New York, however, the facility was renamed in 2008 for a private equity titan. There was a whole fight about just where and how many times he could get his name incised on the façade.

Unlike the borough branches, the central library does not lend books. It's a research institution, and compared to establishments of the same caliber – the Library of Congress, say, or the collections of Harvard and Yale – it is exceptionally open. You don't need an academic affiliation. You don't need to pay for a reader's ticket. You don't even need to come up with a convincing excuse to call up Walt Whitman's manuscripts if you want to have a rifle through. Just fill out a call slip and you can have it in about an hour.

The new Central Library Plan, though, will move 3m books (about 60% of what's now on site) out of the central facility, to be immured in some bunker in New Jersey. Researchers have been promised that they can summon these books with a day's notice. But the library already promises that for books currently off-site, and it doesn't really work that way; in practice, it takes closer to two or three days. One skeptical professor at CUNY, the public university whose students rely heavily on the library, wondered at an acrimonious debate whether the NYPL expected "the traffic on the New Jersey Turnpike was going to decrease."

What will take the place of the books? Well, the closed stacks will be smashed open to make way for a smaller lending library, to supersede the large one across the street from the main facility which the NYPL plans to sell off. That worries not just researchers but architectural preservationists. The library, designed by Carrère and Hastings, is a masterpiece of engineering; unusually, the grand reading room sits at the top of the building, perched on stacks that were state of the art in their day. (Norman Foster, the world's richest architect and the very predictable choice to renovate the library, has not yet published his designs.)

And there will be lots of computer terminals, too, which will surely look very shiny on opening day but, history suggests, will be outdated before long. Also, café spaces. Several. With wireless. To lounge in. You will have to go to Columbia or NYU to do serious research, if you can wangle a library card; as for 42nd Street, I'm sure it will be a beautiful place to update your Facebook status.

The library insists that cafes and wireless are what people want – or so say the consulting firms called in to speak for us. It also argues that the collection is just eating up space, since a large fraction of the books is "never" or "rarely" called up, and so no one will miss them when they're gone. For a start, that's misleading – I myself regularly fail to call up books because it would take days to fetch them. They remain in their bunker, neglected and unread.

More than that, though, it's not germane. A research library has a different mission from a lending library; it's there to put everything, not just the most popular volumes, at our disposal. If you hit an intriguing footnote that references another publication, or if you find an irregularity in a text and want to check it against another source, all you have to do now is grab one of the library's stubby golf pencils, write down the title, and it's yours. That will soon be gone, and its effect on research will be brutal if not mortal.

Of course, there are a few grumblers with a Luddite attachment to musty print, but books themselves are not really the issue. The library bulges with maps and manuscripts, photographs and ephemera. Books are just one kind of resource. But, as of today, there is no substitute for the collection of print books – not yet and not foreseeably. Digitization of books remains in its teething stage, and as any archivist will tell you, if you're building a long-term collection, analogue wins over digital every time. (The Gutenberg Bible is holding up a lot better than your VHS collection.) Talk about the promise of digitization or the belatedness of print is a smokescreen to obscure a larger abdication: the library exists to maintain a collection, in perpetuity, for everyone.

Besides, the primary hurdle with digitization isn't really technology. It's law. Publishers have hesitated to offer ebooks to libraries; lending licenses for ebooks are as expensive as print copies; and since a judge halted its expansion in March 2011, Google Books has been effectively dormant.

Decades' worth of copyright litigation lies before us, and there's no reason to assume that some, as yet unknown digital resource will offer researchers a fraction of the value the library now does. Perhaps, copyright hardliners will win, and books published before the 1920s will remain unavailable in digital form. Or perhaps, untold millions of books will be digitized – which would mean readers could access them at any of the dozens of branch libraries, or at home, or on their phones, or with their nifty virtual reality glasses.

Digitization may succeed or may sputter. But exiling the majority of the book collection is premature either way.

The central library plan might not be irredeemable. Several advocates have proposed a sensible alternative that would keep most of the books in town. But the NYPL has shown no inclination to listen to its own users, or even to make its deliberations public, and that is the truly worrying thing. Replacing books with people may look accessible and anti-elitist. But the real popular gesture is to keep research free for all.

Instead, on the advice of some of the world's most profitable consultancies and a board full of oligarchs, we are being told that what we really deserve is not a world-class library, but comfy chairs and blueberry muffins.