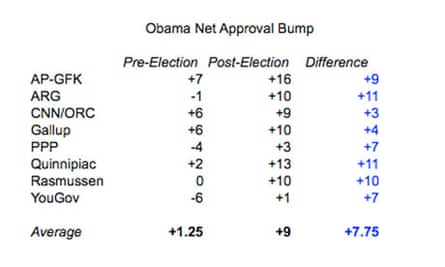

President Barack Obama has received a bump in his job approval figures. Obama's net approval stands at +9 percentage points in post-election polls. That's the highest it's been since the killing of Osama Bin Laden.

Why is Obama's approval on the rise and does it mean Republicans might be more supportive of him in the months to come?

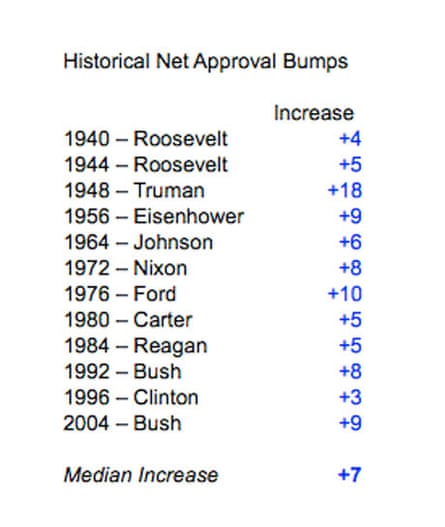

All presidents running for re-election since 1940 have seen a post-ballot rise in their approval rating. The reason is fairly simple: voters give the president a winner's boost or loser's sympathy rally regardless of whether the president wins or loses. Take a look at the differences in estimated historical approval on and in the month following election day.

With the exception of a large bounce for Harry Truman, all post-election gains in the month following an election have been between three and 10 points. The median rise in a president's approval after they've run for another term is seven points. Bounces haven't increased or decreased in recent years, and there seems to be no difference in bounce depending on whether an incumbent lost or won re-election.

Obama's picked up an average of 7.75 points in net approval when comparing pollsters who had pre-election and post-election polls. That puts Obama right in the middle of the pack.

This analysis differs with Micah Cohen's of the New York Times who found that bounces have been receding in recent years and that Obama's bounce is smaller than normal. My examination is distinct from Micah's for a few reasons.

For many years, the last approval rating polls were taken weeks and sometimes months before the presidential election. As Micah points out, he is comparing these long before election surveys with those after the election.

I've taken a slightly different track. I've utilized the loess (local regression) estimated net approvals on election day since 1940 as calculated sometimes by Nate Silver and sometimes myself. This often shrinks the gap between pre-election and post-election net approval as some of the bounce apparent in Micah's dataset is merely because approvals shifted, sometimes significantly, between the last pre-election poll and election day.

Jimmy Carter for example had a final pre-election net approval of -18 in a September 1980 Gallup survey, but his estimated net approval by election day had already fallen to -27. Hence, his average net approval in the month following the election of -22 is actually a slight improvement as opposed to a drop.

The reason why I see Obama's approval bump as being on average with historical data is because I look at all pollsters and not just Gallup.

Obama's four-point Gallup jump is somewhat weaker than the average of all polls. Given Gallup's polling issues this year, I'm more trusting of the average of polls.

You might be wondering whether Obama's honeymoon will hold. Most presidents run into a wall at some point in their second term. Presidents Eisenhower, Johnson, Nixon, Reagan, and George W Bush all had their approvals drop. Eisenhower and Reagan recovered, while the others did not. President Clinton saw his approval rating remain relatively steady, even with the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

Whether Obama's approval rating stays level, rises, or falls will be mostly dependent on whether the economy improves or enters a downfall. Obama could also be hurt by a political scandal like Nixon and Reagan. So far in his presidency, Obama has managed to remain relatively scandal-free.

What won't likely change is that Obama, as George W Bush before him, will remain a polarizing figure. Indeed, we would always expect that Democrats will approve of Democratic presidents in greater numbers than Republicans. Likewise, Republicans will always approve of Republican presidents at a higher rate than Democrats.

The difference with Bush and Obama is the gap in presidential approval between the parties has sharply increased in recent years. Consider the cases of four incumbents who came within a few points of losing or winning in the last 65 years.

Harry Truman and Gerald Ford won just a little south of 50% of the nationwide vote. I estimate that Truman garnered election day approval from about 60% of Democrats and 30% of Republicans – a 30-point difference. Meanwhile, 70% of Republicans approved of Ford's job performance and about 35% of Democrats – a 35 point gap – on election day.

George W Bush and Barack Obama won just a little north of 50% of the vote in their re-election efforts. Bush's election day approval among Republicans was 93% and only 11% among Democrats – an 82-point difference. This year Obama's approval in the days leading up to election day was at 92% with Democrats and a miniscule 6% with Republicans – an 86-point gap.

Some might argue that Bush and Obama were simply more divisive, though I disagree. It's more that the voters are more closely aligning themselves with the parties that best represent them ideologically. There are barely any conservative Democrats and even fewer liberal Republicans voters anymore. More to the point, the correlation between ideology and party identification has more than doubled over the last 30 years. There simply isn't the opportunity to win approval from ideologically like-minded voters from the other party because they mostly don't exist.

Thus, even if we see President Obama maintain his post-election bounce, Republicans are still going to dislike him strongly.