Obama's Edge: The Ground Game That Could Put Him Over the Top

In a close election, the president's sophisticated organization -- which Republicans don't seem to have matched -- could make all the difference.

STERLING, Virginia -- A giant chalkboard takes up a wall in this unassuming office suite hung with Obama signs, one of more than 60 campaign offices for the president in this battleground state. On it is drawn a calendar of the final weeks before the election. Phone banks, canvasses, and campaign events are marked in color-coded chalk. And every Saturday through Nov. 6, in capital letters, is marked "DRY RUN" -- a precision-timed Election Day simulation drill, where everything from data reporting to snacks is rehearsed down to the minute.

Forget the polls, the debates, the last-minute ads and volleys of insults. This is how the Obama campaign plans to win the election.

Four years ago, Barack Obama built the largest grassroots organization in the history of American politics. After the election, he never stopped building, and the current operation, six years in the making, makes 2008 look like "amateur ball," in the words of Obama's national field director Jeremy Bird. Republicans insist they, too, have come a long way in the last four years. But despite the GOP's spin to the contrary, there's little reason to believe Mitt Romney commands anything comparable to Obama's ground operation.

And this time, Obama may actually need it.

Though he trounced John McCain organizationally four years ago, the irony was that Obama didn't really need his sophisticated field organization. Riding a wave of voter enthusiasm and Bush fatigue, and crushing McCain with fundraising and TV ad spending, Obama almost certainly would have won the 2008 election anyway. The political operative's rule of thumb is that organization can increase your share of the vote by two percentage points; Obama won the national popular vote by seven points. One academic study looked at Obama's edge in field offices and concluded they probably put a couple of extra states in his column, but he would have won without them.

This year is different. The polls are so close that a lively partisan meta-fight has broken out over which side actually has the upper hand going into the final stretch, with Romney claiming momentum is on his side, while Obama clings to slim leads in enough swing states to take the Electoral College. In an election that's tied in the polls going down to the wire, Obama's ground game could be crucial.

In the closing days of the race, "we have two jobs," Obama campaign manager Jim Messina said Tuesday. "One, to persuade the undecideds, and two, to turn our voters out." The former is the job of the president and his TV and other media ads. As for the latter, "That's the grassroots operation we've been building for the last 18 months."

The Field-Office Gap

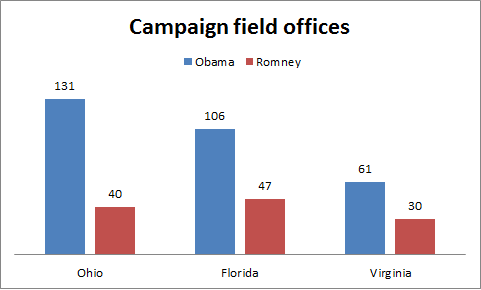

While Obama's office in Sterling is one of more than 800 across the country -- concentrated, of course, in the swing states -- Romney commands less than half that number, about 300 locations. In the swing states, the gap is stark. Here's the numerical comparison in what are generally considered the top three swing states -- Ohio, Florida and Virginia:

But the difference isn't just quantitative, it's qualitative. I visited Obama and Romney field offices in three swing states -- Ohio, Colorado and Virginia -- dropping in unannounced at random times to see what I could see. There were some consistent, and telling, differences.

Obama's office suite in Sterling was in an office park next to a dentist's office. The front window was plastered with Obama-Biden signs, the door was propped open, and the stink bugs that plague Virginia in the fall crawled over stacks of literature -- fliers for Senate candidate Tim Kaine, Obama bumper stickers -- piled on a table near the front reception desk. In rooms in front and back, volunteers made calls on cell phones, while in the interior, field staffers hunched over computers. One wall was covered with a sheet of paper where people had scrawled responses to the prompt, "I Support the President Because...", while another wall held a precinct-by-precinct list of neighborhood team leaders' email addresses.

Only about a mile down the road was the Republican office, a cavernous, unfinished space on the back side of a strip mall next to a Sleepy's mattress outlet. On one side of the room, under a Gadsden flag ("Don't tread on me") and a poster of Sarah Palin on a horse, two long tables of land-line telephones were arrayed. Most of the signs, literature, and buttons on display were for the local Republican congressman, Frank Wolf. A volunteer in a Wolf for Congress T-shirt was directing traffic, sort of -- no one really seemed to be in charge and there were no paid staff present, though there were several elderly volunteers wandering in and out. The man in the T-shirt allowed me to survey the room but not walk around, and was unable to refer me to anyone from the Romney campaign or coordinated party effort.

These basic characteristics were repeated in all the offices I visited: The Obama offices were devoted almost entirely to the president's reelection; the Republican offices were devoted almost entirely to local candidates, with little presence for Romney. In Greenwood Village, Colorado, I walked in past a handwritten sign reading "WE ARE OUT OF ROMNEY YARD SIGNS," then had a nice chat with a staffer for Rep. Mike Coffman. In Canton, Ohio, the small GOP storefront was dominated by "Win With Jim!" signs for Rep. Jim Renacci. Obama's nearest offices in both places were all Obama. In Canton, a clutch of yard signs for Sen. Sherrod Brown leaned against a wall, but table after table was filled with Obama lit -- Veterans for Obama, Women for Obama, Latinos for Obama, and so on. The Obama campaign uses cell phones exclusively, while the Republicans use Internet-based land line phones programmed to make voter calls. Every Obama office has an "I Support the President Because..." wall, covered with earnest paeans to Obamacare and the like.

In a technical sense, the Romney campaign actually does not have a ground game at all. It has handed over that responsibility to the Republican National Committee, which leads a coordinated effort intended to boost candidates from the top of the ticket on down. The RNC says this is an advantage: The presidential campaign and the local campaigns aren't duplicating efforts, and the RNC was able to start building its ground operation to take on Obama in March, before Romney had secured the GOP nomination.

"The Romney campaign doesn't do the ground game," Rick Wiley, the RNC's political director, told me. "They have essentially ceded that responsibility to the RNC. They understand this is our role." The disadvantage of this is that the RNC is composed of its state Republican Parties, which vary dramatically in quality. States like Florida and Virginia have strong Republican operations, while those in Iowa and Nevada haven't recovered from attempted takeovers by Ron Paul partisans, and the Ohio GOP still bears the scars of a protracted leadership fight earlier in the year.

And while the RNC and Romney campaign exert a centralizing influence, there is nowhere near the standardization of Obama's Starbucks-like franchise operation, each with its identical "I Support the President Because..." poster.

The Real-Estate Game

What's the point of all those campaign offices, anyway? Republicans scoff at the Obama campaign's proliferation of field offices as a symbol of a liberal big-government mentality. "The Obama campaign thinks, 'If we put 100 offices in this state, we're going to win,'" the RNC's Wiley said. "We take a smaller, smarter approach, just like we do for government. I will guarantee you they have three times as many offices in Wisconsin as we do. We decided we needed 24. Bush-Cheney in 2004 had 10."

The Obama campaign actually agrees: Real estate isn't the point. "Our focus is on having a very decentralized, organized operation as close to the precinct level as possible," Bird said. In addition to all those offices, the campaign operates out of dozens of "staging locations," many of them the living rooms of neighborhood leaders who have been working with their volunteer teams for a year or more, fanning out into the communities they know firsthand.

"Community organizing is not a turnkey operation," Bird says. "You can't throw up some phone banks in late summer and call that organizing. These are teams that know their turfs -- the barber shops, the beauty salons; we've got congregation captains in churches. These people know their communities. It's real, deep community organizing in a way we didn't have time to do in 2008."

Instead of campaign offices, the RNC likes to tout voter contacts, a metric that includes the doors knocked and phone calls made by volunteers, and which cannot be independently verified. (It still counts if no one answers the door, I was told, because the canvassers leave literature behind.) As of Tuesday, the Republicans boasted of nearly 45 million volunteer voter contacts since spring, including 9 million doors knocked, which they say is four times as many as the entire 2008 campaign and 12 times as many as the same time in the 2008 cycle. The number of phone calls made, they claim, is triple what it was at this time in 2008.

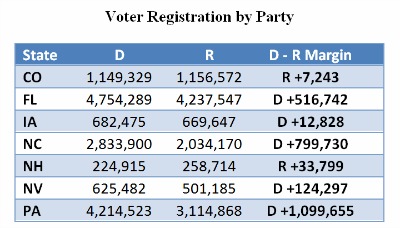

The Obama campaign doesn't release equivalent statistics, preferring to focus on publicly available data for voter registration and early voting. As of last week, there were more registered Democrats than Republicans in Florida, Iowa, North Carolina, Nevada, and Pennsylvania; voters do not register by party in Ohio, Virginia or Wisconsin. Republicans led in registration in Colorado and New Hampshire.

Here are the voter registration totals as of the end of last week for the swing states that register voters by party:

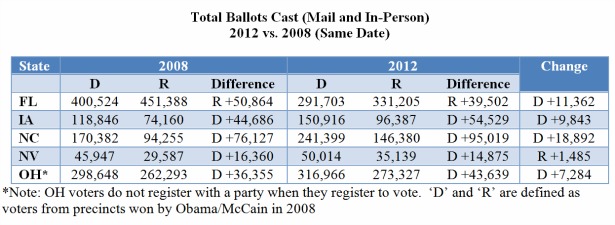

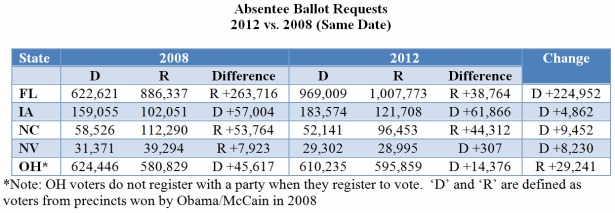

Democrats also say they have an edge in early voting in states where it has begun. In Iowa, North Carolina, and Nevada, more Democrats than Republicans had cast ballots as of Monday. In Ohio, more votes had been cast from precincts Obama won in 2008 than from precincts won by McCain. In Florida, more Republicans had cast ballots -- absentee balloting is typically a GOP strength in the state, and early voting, which Democrats tend to dominate, has not yet begun. But Florida Democrats note that Republicans' early advantage is reduced from this point in 2008.

Republicans counter that their partisans are outperforming their share of voter registration in early and absentee voting in many states, and that they are getting out more voters than 2008. But to the Obama campaign, the voting statistics are evidence that they are shaping an electorate to look different than the public polls. "We think that people aren't always getting it right about who and what this electorate is going to be comprised on Election Day," Messina said. "We continue to think there's going to be a higher percentage of minority and young people than some are forecasting."

It's a simple, eternal political truism: Democrats are less likely to turn out to vote than Republicans. It's reflected in the difference between polls of registered voters and those of likely voters -- in Gallup's latest survey, for example, Obama and Romney were tied, 47-47, among registered voters, but Romney led 50-46 among likely voters. If the Obama campaign, through organization and elbow grease, can drive more of those less-likely voters to the polls, the president's chances get better.

Invisible to the Naked Eye

In Springfield, Virginia, last weekend, I went out canvassing with two 17-year-old Republican volunteers. Along with a dozen others, they picked up their clipboard outside a Baskin Robbins, then drove to a neighborhood of condo buildings and row houses. Consulting a printed-out Google map for guidance, the pair -- one chubby and wearing a lacrosse hoodie, the other taller and clad in an American-flag polo -- worked their way down a printed list of names, each accompanied by a barcode and a series of bubbles to be filled with survey responses.

It was a Redskins football Sunday, and out of a dozen homes we hit, only two doors were answered. Both homes had signs in their yard for Romney-Ryan, Senate candidate George Allen, and local congressional challenger Chris Perkins. One said he had already voted; the other said he'd just been out canvassing himself.

The ground game can be difficult, even impossible to assess with the naked eye. The real keys to the RNC's organization were hidden in the barcodes on those sheets -- the way the campaign had determined whose doors to knock on. The fact that my canvassers only encountered voters Romney, Allen, and Perkins clearly had sewn up might be a sign of poor targeting, since campaigns' time is better spent turning out people who might not vote without the extra encouragement. Or it might have been a fluke.

Similarly, all the dueling claims about voter contacts, and what I was able to observe by visiting field offices, really told me little about the true state of the ground game. It's not about how many people you contact; it's who you're contacting and how. In 2008, the Obama campaign took data-based voter targeting to a previously unseen level, as Sasha Issenberg details in his new book The Victory Lab. In 2012, they've far surpassed those techniques, in part by integrating field techniques with digital operations.

Some Republicans admit that the ground game is a weakness for the party. In Colorado, one top GOP consultant who has worked on presidential campaigns told me he mentally added 2 to 4 points to Obama's polls in the state based on superior organization. In Florida, GOP Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart said Republicans would win in other ways: "They're very organized. They're very, very organized, and you have to admit they're very organized," Diaz-Balart said of the Democrats. "However, I think Republicans are very motivated."

We may not be able to fully size up the campaigns' ground games and their effect until Election Day -- and maybe not even then. But what struck me most, in talking to Republicans about their ground game, was the extent to which they admitted they weren't even playing the game. On Obama's voter registration advantage, for example, Wiley said it just wasn't something Republicans had really tried to do.

"We did some voter registration programs. They weren't massive in size, because most Republicans are already registered," he said. (This is somewhat belied by the GOP's hiring of a sketchy registration contractor in Florida.) Instead of trying to register more Republicans, Wiley said, the RNC focused its efforts on talking to independents. "That's much more reliable, because they're already registered to vote," he said. "There are enough voters on file in any given state that are registered to vote already that you can win with them. You don't need to add to the mix."

It's true that the Obama campaign's strategy is far more reliant on bringing new voters into the electorate -- particularly the young and minority voters who are less likely to register and vote. But if the Democrats can do that, it could make a big difference in a close election.

"If there's a blowout election, the ground game is nice," Bird, the Obama field director, said. "But in a state-by-state close contest for electoral votes, where it's deadlocked going in, if you know you expanded the electorate, and you know who those people are, and you have volunteers trained to turn them out -- that's what the ground game is engineered to do."