Writing the Book on Reinventing the Book

Two professors' inquiry into the written word is trying to demolish paper vs. digital binaries.

Over more than five centuries, books have evolved from collections of folded and gathered pages bound between covers to collections of screens connected to a digital cloud. Yet despite the rise in tablet and ebook usage, print persists. Advocates of hard copy continue to make physical books that fill what few bookstores remain. In other words, the state of books today is multifaceted. How can someone possibly make predictions about books' future?

Leslie Atzmon and Ryan Molloy, Eastern Michigan University art professors specializing in graphic design, have been trying to figure that out. Their Open Book Project has resulted in an exhibition, workshops, and a 248-page book, all spotlighting artists and designers exploring various forms that books might take.

After putting on an Open Book exhibition in 2010, Atzmon and Molloy received a $35,000 National Endowment grant in 2012 to organize a series of experimental book workshops. Guest artists-designers ran them, including Denise Gonzales Crisp, Chris Baker, Jon Sueda, Everett Pelayo, Danielle Aubert, Edwin Jager, Paul Elliman, and Max Goldfarb. The goal of these sessions was to help define what the classic book—and the new book—could be.

"The notion that print books are totally obsolete, and that they are in the midst of being superseded by digital books, doesn’t make sense,” Atzmon says. “Neither does the idea that e-books are a menace that has destroyed the future of print books.”

Molloy adds: “If we define a book solely as a paper-based physical object, signs of its decline are definitely there. Moreover, traditional books move into the territory of nostalgia and operate as precious objects. If we question what a book may be, a vehicle for communication of language (written or pictorial), this opens up new territory and steers us away from this notion of demise.”

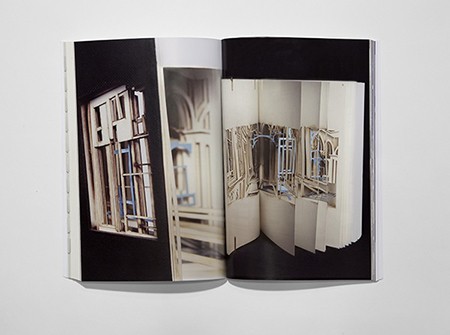

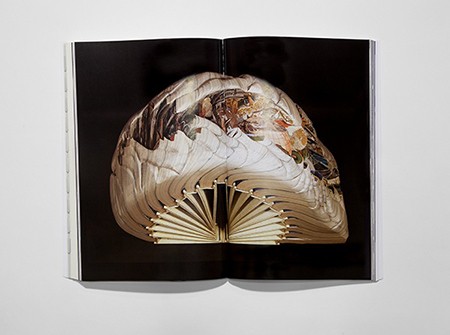

Towards this end, the Open Book book—which is covered with an intricate, detachable laser-cut casing—is an amalgam of essays on and artwork made from books. “Not all of these books are made from and with paper-based books,” Atzmon says. “We purposely sought book-like work for the Open Book exhibition that transcended paper media.”

In that exhibition, there were physical books made from plexiglass and metal, video-game books, programmed motion-graphic books on iPods or projected onto the wall, and photographic images of books. All of this gives the audience “novel ways to think about the book as a physical three-dimensional object,” Molloy says. “Doug Beube's book that is made of maps and zippers, for example, offers us an interesting way to think about books becoming sculptural objects; at the same time, he creates a system for building a book (the "pages" can be reorganized, reattached, reconfigured, reassembled). ... To me, Penelope Umbrico's Embarrassing Books communicates the importance books have for us, even without any written content (or at least written content that is readable by viewers). In her piece the physical object is most important.”

What about the possible impulse to romanticize physical books just for sentimental, nostalgic reasons? “According to Marx,” Atzmon says, “fetishized objects seduce people into vesting them with a spirit and a will, what Dick Houtman and Birgit Meyer sarcastically call ‘scandalous materiality.’” In her opinion, these negative attitudes towards "fetishization" can be counterproductive. “What's wrong with loving and valuing a book thing in an intense way?”

But, Molloy says, “it is unhealthy when we begin to look at books solely as objects of display, which is what comes to mind when I think of how people fetishize books. There is something magical about books that warrants some degree of fetishizing, but by and large I think ‘book lust’ is really nostalgia.”

The Open Book Project's goal is to get past the simplistic thinking that sometimes characterizes discussions of the state of books. “People don't necessarily think about how digital and physical books are evolving together, or the implications of contemporary artists and designers' explorations of digital, physical, and hybrid book media," Atzmon says. "It's more common for designers to consider how a cool-looking book communicates certain design concepts, or how the newest media for book content is ‘better’ than old media, or vice versa, how new or digital book media is ‘destroying’ traditional books.”

The takeaway lesson? Inconclusive. “I don't know if I have a definition of what a 'new book' would be,” Molloy says. “To say that works that are created for digital distribution and viewership are new is false. Digital technologies have existed for quite some time. I think if there was to be a new book then it would take the form of re-defining what a book is.”

Yet coming up with solid definitions isn't the point of the Open Book Project. “I don't think that there is any single answer as to what is a book and what is the future of the book,” Molloy says. “And the fact that we do not have an answer after four workshops, one exhibition, and a book is perhaps the best conclusion.”