Cell phones replacing landlines are making it difficult to accurately locate people who call 911 from inside buildings. If a person having a heart attack on the 30th floor of a giant building can call for help but is unable to speak their location, actually finding that person from cell phone and GPS location data is a challenge for emergency responders.

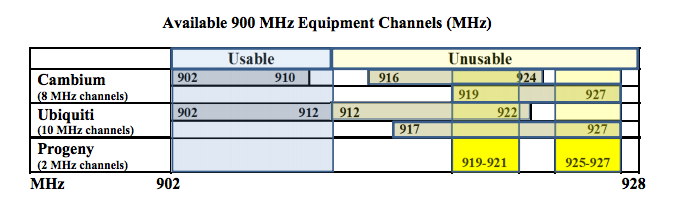

Thus, new technologies are being built to accurately locate people inside buildings. But a system that is perhaps the leading candidate for enhanced 911 geolocation is also controversial because it uses the same wireless frequencies as wireless Internet Service Providers, smart meters, toll readers like EZ-Pass, baby monitors, and various other devices.

NextNav, the company that makes the technology, is seeking permission from the Federal Communications Commission to start commercial operations. More than a dozen businesses and industry groups oppose NextNav (which holds FCC licenses through a subsidiary called Progeny), saying the 911 technology will wipe out devices and services used by millions of Americans.

Harold Feld, legal director for Public Knowledge, a public interest advocacy group for copyright, telecom, and Internet issues, provided the best summary of these FCC proceedings in a very long and detailed blog post:

Depending on whom you ask, the Progeny Waiver will either (a) totally wipe out the smart grid industry, annihilate wireless ISP service in urban areas, do untold millions of dollars of damage to the oil and gas industry, and wipe out hundreds of millions (possibly billions) of dollars in wireless products from baby monitors to garage door openers; (b) save thousands of lives annually by providing enhanced 9-1-1 geolocation so that EMTs and other first responders can find people inside apartment buildings and office complexes; (c) screw up EZ-Pass and other automatic toll readers, which use neighboring licensed spectrum; or (d) some combination of all of the above.

That’s not bad for a proceeding you probably never heard about.

All eyes on the FCC

While the Progeny proceeding has flown under the radar, the FCC may be inching toward a decision. The FCC's public meeting next Wednesday will tackle the problem of improving 911 services. Feld says the FCC seems to be close to making a decision, although the FCC itself did not respond to our requests for comment this week. All the public documents related to the proceeding are available on the FCC website.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...