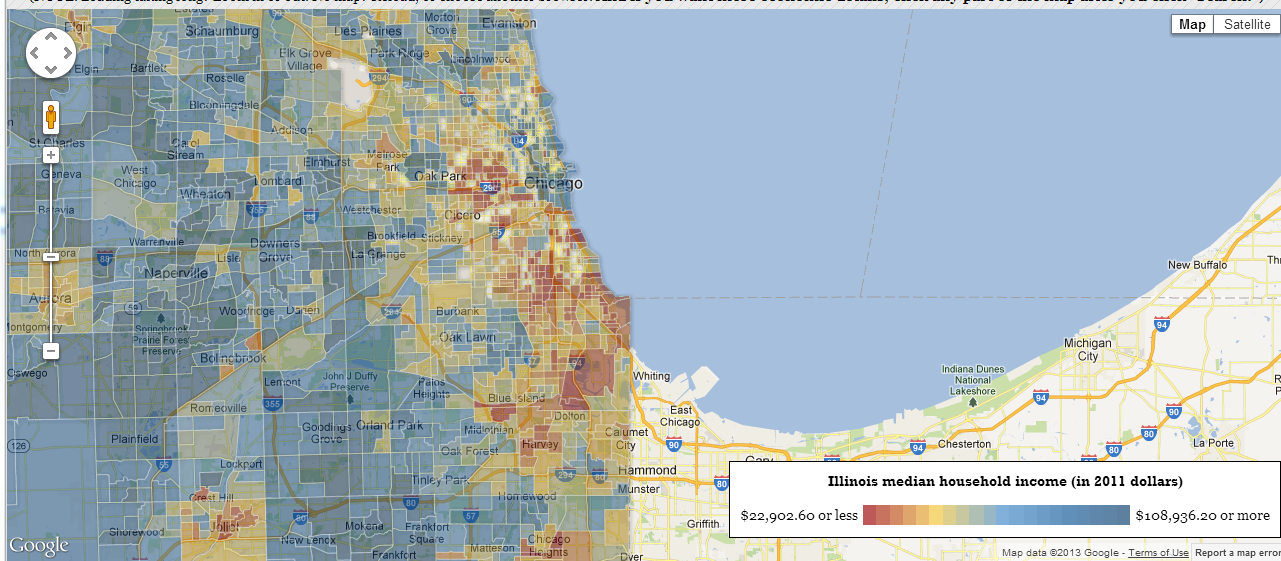

A recurring conversation in sociology is that of segregation. While we are decades away from Jim Crow, the weight of the evidence since the 1980s is that while our population is diversifying, we’re not necessarily content with living alongside those who appear different from us. In most of the research to date, segregation has often inferred race as the main marker of difference. But a few years ago, new research was emerging that suggested income was now gaining in prominence. With the availability of a new interactive online tool, we’re able to see how income segregation appears today. Here’s a screenshot of the Chicago area based on the website, richblockspoorblocks.com (Read on to see why I chose Chicago for this example):

Using income alone, we see a pattern familiar to those who understand racial segregation. The more urbanized areas of Chicago have concentrated poverty whereas the outlying areas generally show significantly higher income levels. Substitute low income with racial minority status and the picture looks very similar. So which one is it, racial segregation or income segregation? This is the big debate. Recently published research by sociologist Lincoln Quillian provides a new perspective that essentially shows us that it’s both.

Back in 1993 a landmark book, American Apartheid,

revealed the persistence of racial segregation and its effects on minority populations. Racial residential segregation places minorities in concentrated environments of poverty which are linked to higher criminal activity, violence, and poorer schools (not to mention inadequate access to good health care, and nutritious food). As Quillian summarizes, “Massey’s (1990) core point [is] that segregation and minority poverty rates interact, or intensify in combination, to produce concentrated poverty” (p.355). This point is more formally defined as two processes: racial segregation and class segregation within race. Look again at the map of Chicago and you can almost see this argument; if greater income is coupled with white racial status, then the higher income levels tend to be more white. Within the poorer census tracts, so the argument goes, there will be segregation between poorer minorities and richer minorities. But Quillian’s study, which uses Chicago census tracts as his main example, goes one step further and provides the missing methodological key to Massey’s study: “the segregation of high- and middle-income members of other racial groups from blacks and Hispanics” (355). Stated differently, to understand how concentrated urban poverty and racial segregation work, we have to account for the difference in poverty rates between the different racial groups. It’s not only that whites and blacks are segregated, nor that richer blacks are slightly segregated from poorer blacks. It is also that whites have much less poverty as well. Since white poverty rates are much lower than blacks, neighborhoods with middle-class blacks are more likely to have poorer neighbors (regardless of race) than if the neighborhood was middle-class and white. The “three segregations” serve to distance whites from blacks (and Hispanics) generally and conversely amplifies the combination of black segregation and black poverty. This is a powerful explanation. We learn from this study that the underlying logic of racial and class segregation still go together despite increasing diversity and calls for colorblindness (which presumes that race doesn’t matter in social and individual outcomes). The integration of nonwhites and whites is very selective and coupled with perceived class of racial minorities. [If readers can’t follow my explanation, here’s another summary of the study).

Given my interest in Asian Americans, I wondered how they fit in this equation. I’ll need to contact Dr. Quillian for the additional analyses he did that accounted for Asian Americans as a separate group (p.365), but I suspect that the other observations we know about this group will explain their role pretty quickly. We know that Asian American poverty is higher than the national average (see pp.34-35 on link to report) (according to the Census Bureau, Asian American poverty increased 46% between 2002 and 2010), while at the same time Asian American household incomes are quite high. This is because Asian Americans are a very diverse group and due to the specific kinds of migration patterns (high-skilled employment, political asylum etc.) some arrive with a lot of resources and others have very little. More than half of the Asian population is foreign-born so these factors still play a sizable role in their poverty or lack thereof. But Asian Americans are also fewer in number compared to other minorities and (this is the big one) they are not often embedded in concentrated communities whether rich or poor. The Chinatowns and Koreatown are still here but they don’t contain a large number of Asians (note that each of these enclaves is a specific ethnic group; “pan-Asian” enclaves don’t really exist) in part because there aren’t as many of them to begin with. So if I could guess, Asian American segregation is fairly rare and the coupling of concentrated poverty and racial segregation doesn’t result in the same amplified results we see for blacks and increasingly for some Hispanics.

As I reflect on it some more I also wonder if predominantly white neighborhoods will absorb Asians and more readily accept their presence as a symbolic gesture toward inclusivity, a means of justifying colorblindness. Given the high incomes of many Asian Americans this seems like a real possibility given the way the three segregations play out. Note that Quillian did not describe segregation from whites, but rather from “non-black neighbors” and I suspect this is because there are just enough Asian Americans in those neighborhoods that one cannot call these exclusively white neighborhoods.

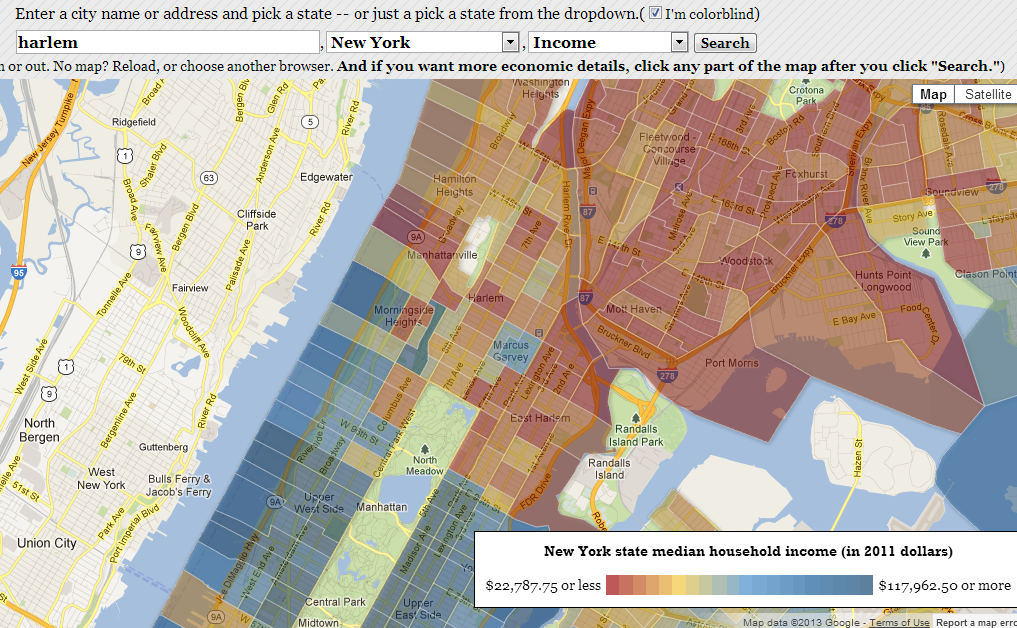

But what about Asian and black residential integration? From a news piece that appeared yesterday, I’m intrigued at the possibility of what might happen in New York. Apparently Chinatown is too expensive for some Chinese to move in; these migrants need a more affordable place to live. Their next choice is east Harlem. Will entry into a predominantly black community perhaps reshape the segregation patterns we see (at least in this city), or will it reflect more of the same, only now including poor Asian Americans? Here’s a screenshot of the richblockpoorblocks site for Harlem: