The women in Barka’s paintings have full lips. The men have broad noses. But although their skin is always shaded grey, the imagery is unapologetically black. No one in Barka’s portraits returns your gaze because, he says, they are, “funky, fly and don’t give a fuck”. The artist dubbed his series Black Romantics, but the label has come to mean something bigger: a new wave of young black artists committed to painting, filming and saluting the style of black Britons.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

“What black romanticism means to me is being in love with yourself,” says Barka. “Being confident in your skin and enjoying every moment of it. The whole black aesthetic is bringing glory to ourselves. I see myself in the people I paint. The women are strong. People say there is an attitude.”

Barka grew up in south-east London when the National Front was on the rise. Rumour has it that, back then, an agreement was made between the fascists and Jamaican rude boys: new migrants from the Caribbean and Africa could settle in Peckham, but if they crossed north into Bermondsey or east into Greenwich their lives would be at risk. The dividing line was Old Kent Road, and Barka’s family lived on the wrong side of it, the only black family on the block.

“It was scary,” says the 28-year-old. “They had their fascist marches on certain days and we were not allowed to play out. We were targeted by racists that lived in our block so we had to move from one part of Bermondsey to another.” But the middle child of six did not channel this terror into animosity or anger. He directed it into his art. His creative output is reflective of an energy spreading through London, across the Channel and into mainland European cities.

“If we weren’t doing the work we were doing, we would not see ourselves anywhere,” says 23-year-old Rianna Parker. Alongside her Lonely Londoners art collective (named after Trinidadian author Samuel Selvon’s 1956 novel) Parker has curated pop-up shows in London and New York on growing up young and black today – art about everything from hair stories to being queer.

Swanzy, the 30-year-old creative behind style zine RoadFemme, agrees. “When I started on Instagram people used to say to me, ‘You’re racist for only posting images of black people,’ but I put out what you don’t see.” RoadFemme started as a streetwear blog; today it is a biannual feminist publication that incorporates storytelling, poetry, art and photography.

Perhaps the spirit of the new black romantics is best captured by 24-year-old performance poet Belinda Zhawi: “It’s about being black and being crazy, fabulous and awesome. People now are just doing their thing and are proud of it.” Belinda’s thing is writing. “The way I see it I’m not consciously writing a black story, I am writing my story and I am black African ... The literature provided in school didn’t relate to me. Reading poets like John Agard gave me the power to tell my story and it’s a black story – of London and my Zimbabwean childhood.”

“Something is happening and could take off,” reckons Zhawi of the growing number of artists on the black romantic scene. When I ask where it came from, she laughs and says: “Tumblr.” Many of Barka’s portraits were inspired by images of black chic found on social media; images that can be found on hashtags like #carefreeblackgirl.

But if the social platform sparked connections, there’s concern about a shrinking physical space for these artists in the capital. Barka’s paintings are on windows thrown out during renovation work to make old social homes appealing to new private buyers. One pane, he claims, survived two world wars but not gentrification. “Black people are getting pushed out of this stage of London’s regeneration,” he says. Parker agrees: “London to me has unsteady foundations – I’m from here but don’t feel supported. It’s not made for anyone who doesn’t have a disposable income.”

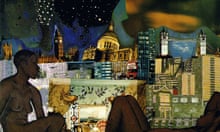

Dandyish film director Shola Amoo’s underground shorts set out to mess with stereotypes, he says: “I think, how can I tackle the dominant image – how do I fuck with it?” His latest, A Moving Image, grapples with the pricing out of working-class residents. “There is a racial element to gentrification,” he says. “Look what’s happened in Harlem or Brooklyn. Brixton and Peckham are the equivalent for black Londoners.”

Though black romanticism is a London story, it is outward-looking and the latest reimagining of black youth culture happening globally. The emergence of the Afropolitan was the response of young, mobile middle classes in Cape Town, Lagos and Nairobi. The Afropunks were born from the alternative scene in Brooklyn. Parker cites the work of young British film-maker Cecile Emeke whose internet-based Strolling series captured the voices of “Afropeans” in France, Italy and elsewhere.

Thirty years ago this month, riots in Broadwater Farm and Brixton defined black British identity as a reaction against state racism. The work of artists such as Sonia Boyce and Yinka Shonibare appeared to comment and critique these racial politics. But it’s not a legacy black romantics want to be defined by.

Barka feels unburdened by the responsibility of political comment: “I would not say my work is political,” he says. “I don’t want to police other people’s lives,” says Swanzy, “I don’t care how people categorise me. I do whatever I feel like. The heart of me is expression.”

Amoo laughs when he is called a black romantic by his friends. “It’s helpful for people to understand my work ... I see myself as Nigerian and a south Londoner but identity is very fluid. On any given day I’m 100 different things.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion